Crocus Attack Ends Lull of Six Years, Raises Question About Law-Enforcers’ Focus

One of the multiple factors that propelled the then relatively unknown apparatchik Vladimir Putin to the pinnacle of power in Russia in late 1999/early 2000, was his ability to convince many members of the Russian elite and the public that he was the kind of leader who not only promised to protect them from the horrors of mass-casualty terrorism, but also delivered on his promises of security, in contrast to the ailing Boris Yeltsin.

The need for such a leader at the time was especially obvious to those who had suffered from or witnessed multiple acts of terrorism committed in Russia in the 1990s, whether or not all of them were, indeed, carried out by jihadists.1 Having been elected president in spring 2000 on a platform with a prominent counter-terrorism component, Putin proceeded to try to deliver on his 1999 promise to “waste them in the outhouse.” At first, his counter-terrorism efforts were not very effective. Eventually, however, a combination of factors—including an increase in the quantity, if not quality, of government force used against non-state actors engaged in political violence, the departure of many Islamist radicals to “greener pastures” in the Middle East,2 and, arguably, increases in living standards—led to a decline in the levels of such violence in Russia by the 2010s, even as abuses at the hands of “siloviki” (the officers of Russia’s so-called power agencies) continued to feed low-intensity insurgency in the North Caucasus (see Table 1 below).

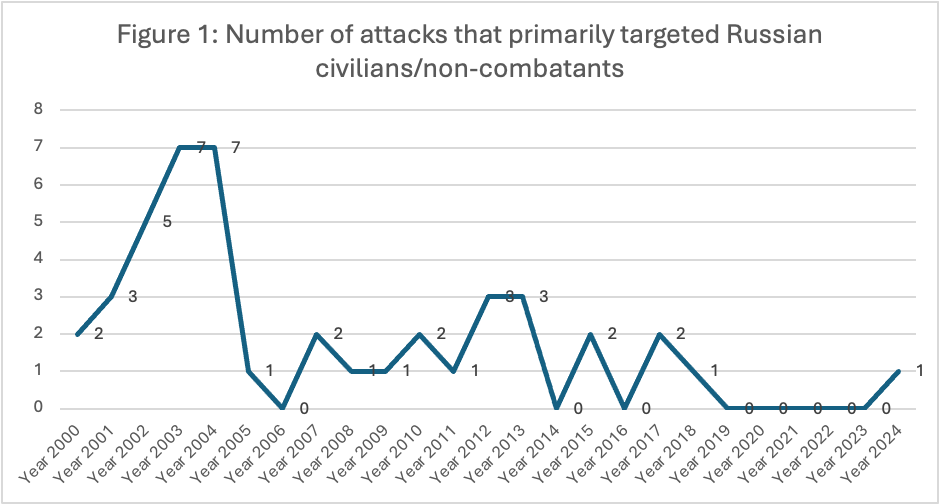

In fact, if one were to analyze attacks executed by non-state actors primarily against Russian civilians in or outside Russia3 during Putin’s rule (i.e. the kind of attack carried out at the Crocus City Hall concert venue outside Moscow), one would notice a lull in such attacks after February 18, 2018, when a gunman shot five and injured four civilians in Dagestan. The attack on March 22 not only ended the lull of 6 years, 1 month and 4 days, it also instantly turned 2024 into the fourth worst year of Putin’s rule in terms of the number of civilians killed in such attacks (see Figures 1 and 2 below), according to my calculations based on data mined from the Caucasian Knot’s timeline of political violence in Russia, as well as from reports in the Russian and Western press. If one were to look beyond these sources and analyze the relevant data in the Global Terrorism Database (GTD), which has data through 2020,4 one would find many more cases than in Table 1. However, the trends revealed by plotting the GTD data (see Figures 3 and 4 below) are not dissimilar to the ones gleaned from the author’s monitoring of Russian media for major cases (see Figures 1 and 2 below) with the GTD database including 34 attacks, for which ISIS and its North Caucasian branch claimed responsibility in 2015-2020.5

Incidentally, it was ISIS—whose current leaders have not forgotten what Russian forces did to subdue this organization in Syria as well as in Russia itself—that claimed responsibility for the Feb. 18, 2018, after which the aforementioned lull started, and the March 22 attack, which ended that lull.6 To be more precise, it was ISIS’ Khorasan Vilayat (ISIS-K)7 that claimed responsibility for the March 22 attack, which was allegedly carried out by four citizens of Tajikistan8, who were allegedly assisted by at least seven other natives of Central Asia. Both the U.S. and some of its allies have found the claim by ISIS-K, which has targeted both Russia and Western countries in the past, to be plausible. In contrast, while stating that ISIS members executed the attack, Putin and some of his key subordinates have alleged that the attackers were aided by Western and Ukrainian intelligence services. Putin provided no evidence to support these allegations, which officials in Kyiv9 and Western capitals have refuted,10 while four people close to the Kremlin told Bloomberg that there’s no evidence of involvement by Ukraine.

Does the March 22 attack signal a return of recurrent large-scale terrorism to Russia? Hopefully not and there are multiple ways to lower the probability of such recurrence. Doing so requires drilling down into what drove and drives those behind the terrorist attacks,11 including not only those carrying them out, but also the actual organizers—rather than the ones the Kremlin finds it politically expedient to blame. When doing so, one should, of course, keep in mind that there can be no justification for attacking innocent civilians, and perpetrators of such attacks must be condemned and prosecuted. At the same time, however, while fighting individual manifestations of this evil, authorities also should avoid either condoning or turning a blind eye on illegal methods of handling the suspects.

Subjecting suspects to torture (which has been only recently become a subject of a separate article in Russia’s Criminal Code) of the kind we have seen the suspects in the Crocus attack subjected to, may produce instant gratification for a public demanding revenge as well as some investigative results, but in the longer-term such practices can fuel more attacks, especially as they are now being broadcast on social media. (My research of drivers of political violence in Russia in the 2000s-2010s has indicated that a combination of being at disadvantage socially, being exposed to violent ideologies and experiencing abuses at hands of state representatives (or knowledge of one’s near and near being abused) made the youth of the North Caucasus more likely to resort to such violence.)

The Russian authorities would also do well to have an independent review examine not only the actions of the terrorists, but also what Russia’s law-enforcement, security and other agencies did or did not do to prevent and to respond to this attack,12 including whether the fact that these agencies’ counter-terrorism and counter-extremism branches have increasingly focused on the Kremlin’s political opponents13 may have come at expense of maintain a robust capacity to go after non-state actors seeking to commit acts of political violence against Russian civilians.14

Finally, the review can also, perhaps, explore how and why these agencies have acted on own intelligence15 as well as intelligence shared by other countries, such as the U.S.16 Dismissing warnings from such countries as provocation would be wrong if only, the new Cold War notwithstanding, these countries also have a vested interest in degrading the capabilities of ISIS, which have been targeting them in addition to Russia.17 After all, efforts at degrading this international threat have higher chances of success if those involved in it do not just accept, but also act on intelligence on this threat.

The cut off point for research was 12:00 pm (GMT) March 27, 2024.

Footnotes

- As a journalist in Russia in the 1990s and 2000s, I got a sense of public sentiment toward this issue as I reported from the scenes of some of the most gruesome terrorist attacks in Russia, including the apartment building bombings in Moscow in 1999.

- By “greener pastures,” I am referring to territories in Iraq and Syria controlled by ISIS, al-Qaeda and other jihadist organizations at the time.

- Thus, attacks executed on the orders of states/governments are excluded, as are attacks against public servants, including officials and servicemen not only of the so-called power agencies, but also of other state bodies—including civilian executive agencies, legislatures and judicial bodies—which terrorist actors often include in their lists of “legitimate” targets.

- Excluding attacks on government (diplomatic), police and military targets; and including attacks on airports and aircraft, business, educational institutions, food or water supply infrastructure, journalists and media, private citizens and property, religious figures/institutions, telecommunications infrastructure, tourists, transportation, terrorists/non-state militia, utilities and violent political parties.

- ISIS operations in Russia date back at least to 2015, when Dargin warlord Rustam Asildarov pledged allegiance to this terrorist organization which established its Caucasus Vilayat in 2015, taking responsibility for an attack on civilians in Dagestan that year. The Caucasus Vilayat was primarily manned and led by natives of the North Caucasus, most of whom Russian forces either killed or drove out of Russia. In contrast, the Khorasan Vilayat was partially manned by jihadists from Central Asia, having accepted many fighters from the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan.

- It was not for want of trying that Islamists, who, as Table 1 shows, accounted for the majority of attacks, did not execute any attacks against Russian civilians in 2019-2023. The Russian government daily Rossiiskaya Gazeta reported on March 7, citing the FSB, that the latter had “liquidated members of an Islamic State cell” in the Kaluga region, who had planned an armed attack on a synagogue in Moscow. If one were to include attacks targeting Russian officials, then one should also bear in mind that ISIS’s so-called Khorasan Vilayat claimed responsibility for an attack on the Russian embassy in Kabul on Sept. 5, 2022, in which seven were killed, including the suicide bomber.

- Khorasan is the historical region and realm comprising a vast territory now lying in northeastern Iran, southern Turkmenistan and northern Afghanistan, according to Britannica. Many of ISIS-K’s members are natives of Central Asia.

- Two of them reportedly spent time in Instambul just weeks before the attack, according to NYT, and one of them testified that he had been listening to the preaching of an alleged ISIS recruitet and ethnic Tajik who calls himself Salmon Khorasani, according to Istories.

- It should be noted that, of Russia’s land borders, the closest to Moscow is that with Belarus (450 km by car on the westbound M1 highway), but the border with Ukraine is not much further (about 520 km by car on the south-westbound M3 highway that leads to Ukraine). The four Tajiks, who have been arrested for allegedly carrying out the attack, were reportedly stopped on the M3 highway near the village of Khatsyun in Russia’s Bryansk region (some 377 km west of Moscow on the M3, 183 km from the border with Ukraine and 248 km from the border with Belarus). Thus, it is possible that the gunmen sought to hide somewhere in an area abutting the Russian-Ukrainian front line with the intention of trying to cross it eventually. Putin’s ally and President of Belarus, Alexander Lukashenko, said that the suspects first headed for Belarus until they saw that border security had been tightened, “so they turned away and went toward” Ukraine instead, according to Bloomberg.

- It is not the first time Putin has accused the West of interacting with terrorists targeting Russia. He did so after the hostage-taking in Beslan in 2004, but the U.S. refuted claims of such assistance and RM has found no publicly available evidence that the U.S. ever provided direct material support to armed Chechen separatist groups, much less to North Caucasus-based militants who have engaged in terrorist attacks.

- For one attempt to drill down into the motivation of jihadists from Central Asia, see: Edward Lemon, Vera Mironova and William H. Tobey, “Jihadists from Ex-Soviet Central Asia: Where Are They? Why Did They Radicalize? What Next?,” Russia Matters, Fall 2018.

- Arguably, the March 7 warning by the U.S. notwithstanding, Russian law-enforcement officers didn’t have much time to uncover the plot if it was, indeed, put together over the course of just a month, as R. Politik reported. Nor did Russian law-enforcement rapid reaction units have much time to intercept the gunmen in the course of their attack inside the Crocus City Hall, even though the latter is located530 meters (6 minutes by foot) from the police station of Krasnogorsk district’s Pavshino neighborhood, according Russia’s Yandex map service.The gunmen opened fire in Crocus City Hall at 7:58 p.m. and left it at 8:11 p.m., according to the chairman of Russia’s Investigative Committee Alexander Bastrykin.

- The number of individuals whom Russian law-enforcers arrested and Russian courts sentenced to jail time over what Russian human rights activists describe as political crimes increased in Russia from 40 in 2014 to 600, according to Russia’s Kholod media outelt’s June 2023 interview with human rights activist Sergei Davidson. According to Russia’s OVD-Info watchdog, the number of political prisoners in Russia in 2023 (1010) exceeded that in the late years of the Soviet Union (700).

- For one in-depth examination of this problem, see “Why Russia’s Vast Security Services Fell Short on Deadly Attack,” Paul Sonne, Eric Schmitt and Michael Schwirtz, NYT, 03.28.24.

- Dossier, a Russian investigative resource, reported on March 24, citing a source close to Russian secret services, hat members of Putin’s Secureity Council had received a warning several days prior to the March 22 attack that ethnic Tajiks could be employed in terrorist attacks in Russia.

- Russia’s rejection of the U.S. March 7 warning that violent extremists might want to attack large gatherings, such as concerts, in Russia was not the first time the U.S. and Russia have failed to heed each other’s terror warnings—recall Tamerlan Tsarnaev, for instance.

- Russia and Russians are not ISIS-K’s only target. It has also targeted U.S. personnel in Afghanistan and has planned several attacks in Europe in recent months which were foiled, according to the FT. Among other countries, ISIS-K has targeted France and Germany (in the case of Germany, arrested suspects included Tajik, Turkmen and Kyrgyz citizens). ISIS-K also claimed responsibility for an attack by an ethnic Tajik and another person on a Christian church in Turkey, in which one person was killed in January 2024.

Opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author. Photo by Mosreg.ru shared under a Creative Commons 4.0 license.