Russia’s False Dawn

This article was originally published by the Council on Foreign Relations.

Bottom Line: Summer has seemingly brought a new optimism about the Russian economy. Russia’s economic downturn is coming to an end, and markets have outperformed amidst global turbulence. But the coming recovery is likely to be tepid, constrained by deficits and poor structural policies, and sanctions will continue to bite. Brexit-related concerns are also likely to weigh on oil prices and demand. All this suggests that Russia’s economy will have a limited capacity to respond to future shocks.

Recovery’s Green Shoots

Summer has seemingly brought a new optimism about the Russian economy. Markets have soared: the ruble is the best-performing emerging market currency this year, up over 20 percent since late January against the dollar, and equities have posted double-digit gains. Russian markets have benefited from a range of macroeconomic and technical factors—a moderate pickup in oil prices, a search for yield by investors punished by low or negative interest rates in the industrial world, and a sense that the worst effects of the sanctions are in the past. Also, perhaps counterintuitively, sanctions themselves have provided support for asset prices by limiting (until recently) new issuance from Russian corporations and the government and reducing the supply of investible assets as maturing bonds are repaid. Last month’s decision by the central bank to cut interest rates for the first time since August 2015, and the hope of more cuts to come, has further boosted demand for domestic assets while reducing pressure for appreciation of the ruble. More recently, Brexit concerns had little impact on Russian markets, as the country was seen as largely insulated from global financial market contagion following its turn inward in recent years.

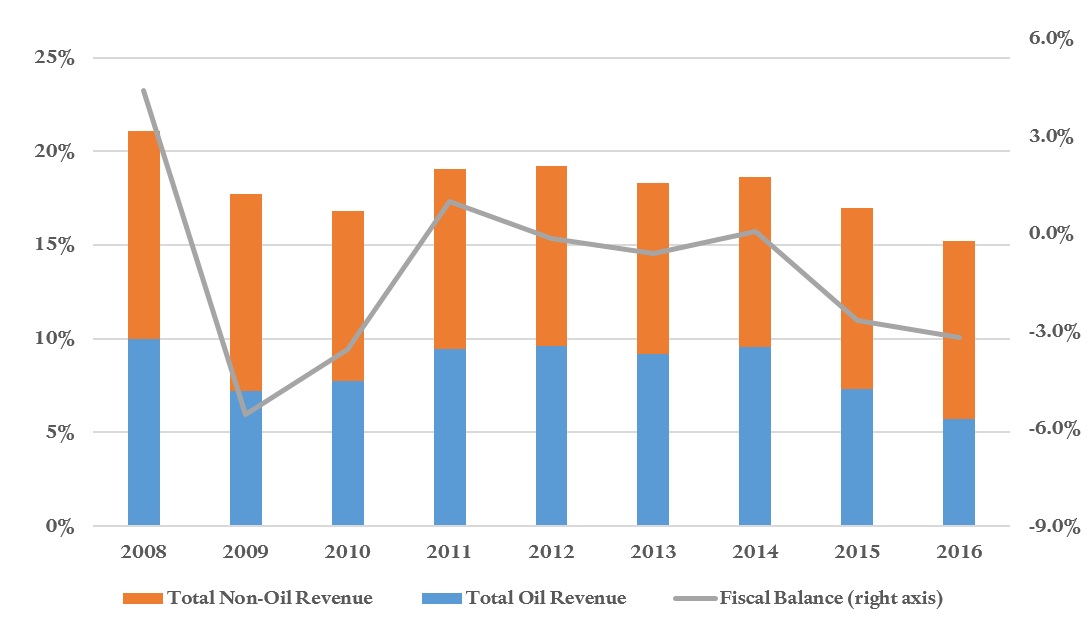

At the same time, there are recent signs of stabilization in the economy. Growth in the first quarter was down 1.2 percent compared to last year, consistent with a bottoming out of the economy in early 2016. Activity has been boosted by improved consumer spending, as well as a shift toward domestic demand and away from imports. Capital outflows also have slowed significantly, helped by firmer oil prices, and the fiscal deficit has been contained (see figure 1). A number of market analysts are predicting that growth will turn positive in the second half of the year, producing full-year growth in 2017 on the order of 1.5 percent after three years of recession. Both the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank also have recently upgraded their forecast and complimented the government and central bank for their strong macroeconomic policy management—including a flexible exchange rate regime, banking sector capital and liquidity, sensible fiscal policies, and regulatory forbearance to keep lending going.

Adding to the optimism is a growing expectation that European sanctions will be eased when they are next up for renewal at the end of 2016. During the June 2016 decision by the European Council to renew the financial, energy, and defense sanctions for another six months, council members reportedly disagreed over the future course of sanctions policies and many members felt that full compliance with Minsk II, the political framework for addressing the conflict between Russia and Ukraine, was not going to be an effective test for future decisions on sanctions.

These are the building blocks of an improving outlook. But I have a less sanguine view: Russia’s recovery may not be enough to bring the country out of its protracted economic crisis.

Three Reasons to Worry About the Russian Economy

The first reason for tempered optimism on the Russian economy is that the macroeconomic developments underpinning the recent boost to growth are running out of steam. The rebound in energy prices this year has produced a welcome influx in foreign exchange, but energy prices are still well below the price needed to balance the budget or provide stability to the balance of payments. Meanwhile, the 37 percent depreciation of the ruble against the U.S. dollar in 2015 provided a price advantage for Russia’s export sector that continued to support demand even as the ruble began to rebound this year. This lag in the response of trade to the exchange rate (called the “J-curve”) is transitory, and the benefits from this earlier depreciation are now largely exhausted at the same time as the more recent appreciation is beginning to bite. Further, the drag to global growth from Brexit is likely to weigh more heavily on oil prices and demand later this year. Thus, although the IMF sees Russia as having an exchange rate policy that is appropriate for the current setting, the policy is not sufficiently competitive to sustain a strong cyclical recovery in growth.

Second, as shown in figure 1, in the past few years deficits have forced a significant running down of Russia’s international funds, a process that cannot continue indefinitely. Russia will empty its Reserve Fund, one of its two sovereign funds (set up to save oil wealth when prices were high), during 2017 and will start dipping into the National Welfare Fund. That fund holds over $70 billion, but it includes illiquid investments in the Russian state development bank Vnesheconombank and other state-favored projects. This suggests the reserves available for budgetary financing are less than they seem.

Unsustainable deficits need not lead to crisis, but they do mean that in future years there will need to be some combination of fiscal tightening and external borrowing to fill fiscal and external gaps. Recent reports suggest that the Finance Ministry is expected to increase domestic borrowing significantly, assuming that international borrowing will remain constrained by sanctions. At the same time, non-sanctioned Russian companies are returning to international bond markets with a wave of new issuance (nearly $2 billion in June alone). In addition, a debate in the Duma over a tightening of capital controls in the fall will be an early test of whether the politics of deficits are changing.

Third, and most important, Russia’s economic downturn reflects deep-seated structural problems that had come to the surface well before the downturn in energy prices in 2014–2015, challenges that will continue to constrain growth. Weak institutions, extensive government intervention in labor and product markets, and disincentives to invest all create an excessive reliance on exports of natural resources. In addition, the prevalence of corruption and weak rule of law will continue to deter investors and businesses from entering the market, especially non-resource sectors, hindering competiveness and innovation. The government’s anti-crisis plan in 2016 speaks to the need for reform: in addition to fiscal stimulus, it contains measures to improve the investment climate by reducing regulatory uncertainty and strengthening judicial processes. But little has been done so far in terms of concrete measures, and I am far from convinced that this program, if implemented, will address the fundamental structural challenges that are preventing the creation of a diversified, market-oriented economy—changes that are needed to sustain above-trend growth and raise real incomes in coming years.

Conclusion

A rebound in oil prices, coupled with sound macroeconomic policies, has moderated the economic downturn and supported domestic financial markets. A modest economic recovery may now be in train. But the fundamentals of the Russian economy remain weak; markets are distorted and too dependent on energy exports. Without a far more comprehensive reform process, tough budget cuts will be necessary over the next few years, and the recovery could prove transitory. In this context, policy uncertainty and political reality weigh heavily on the economic outlook for Russia.

Robert Kahn

Robert Kahn is the Steven A. Tananbaum senior fellow for international economics at the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) in Washington, DC. Kahn has held positions in the public and private sectors, with expertise in macroeconomic policy, finance, and crisis resolution.

Photo credit: Flickr photo by julochka shared under a CC BY-NC 2.0 license.