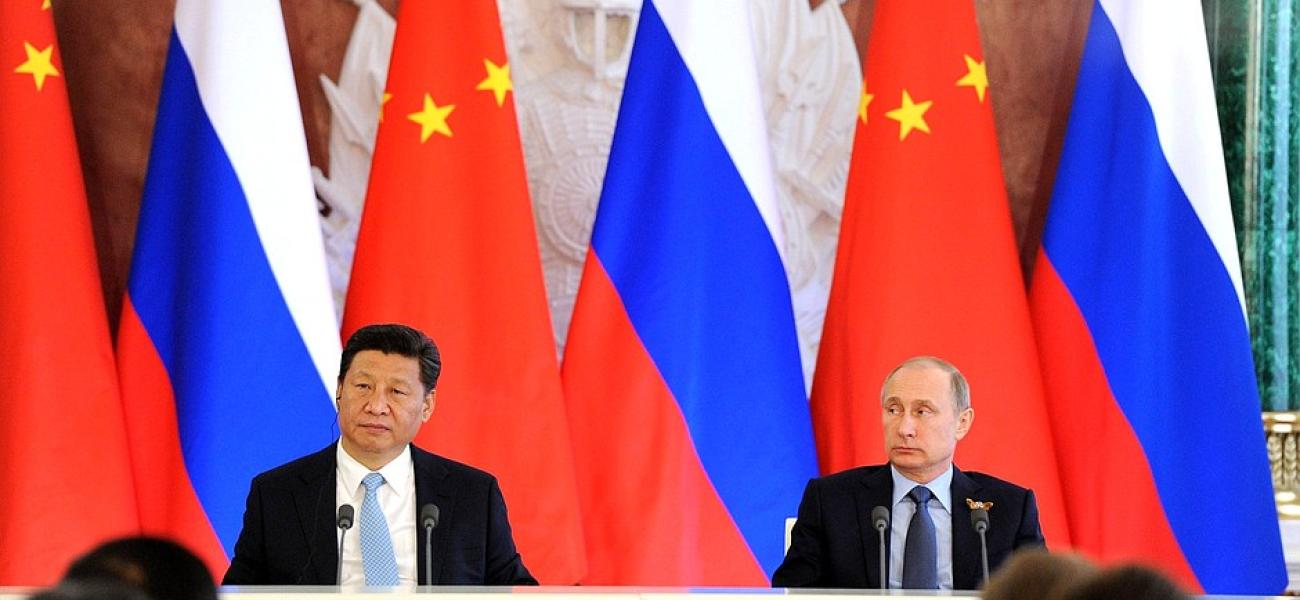

A Sino-Russian Military-Political Alliance Would Be Bad News for America

When Vladimir Putin visits Beijing on May 14-15, he will likely join dozens of other countries’ leaders in singing the praises of President Xi Jinping’s international transport infrastructure initiative, known as “One Belt, One Road,” or OBOR. The fact that the Russian leadership has come around to supporting OBOR even though it will not necessarily be conducive to some of Russia’s vital interests signals Moscow’s readiness to pursue even closer ties with Beijing. This, in turn, could eventually culminate in the establishment of an official military-political alliance between the two countries if tensions between the West and Russia continue. The emergence of such an alliance would be bad news for America.

A positive stance on OBOR would contrast with Russia’s initially wary reaction in 2013 to the unveiling of the program, estimated to cost $1 trillion to $3 trillion and meant to expand routes for Chinese exports to Europe, among other things. At that time some in Russia’s leadership were reported to have concerns that OBOR would compete with Russia’s own integration initiative in the post-Soviet neighborhood and undermine Russia’s role as a bridge between East and West. “A number of people in Moscow, concerned over Russia's fading status as a regional superpower in Central Asia, regarded OBOR as an intrusion into Russia's sphere of influence,” Alexander Gabuev of the Carnegie Moscow Center and Greg Shtraks of the National Bureau of Asian Research wrote of Moscow’s initial reaction to OBOR. That wariness lingered on. Two years after the launch, Russian participants in an OBOR-focused event in Kazakhstan “only thinly disguised their concerns about the project, recognizing the potential damage to Russian geopolitical and economic interests if current routes transiting Russia were replaced,” according to Kemal Kirişci and Philippe Le Corre of the Brookings Institution.

Putin’s decision to attend the summit showcasing OBOR speaks of a shift in Moscow’s position, as have some bilateral agreements in recent years, including one to link OBOR with the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union. What has caused the Kremlin to come out in support of the project even though one of its land routes would bypass Russia in the south while also expanding China’s footprint in the post-Soviet neighborhood, which Russian leaders view as a zone of their country’s “privileged interests”? Perhaps Moscow has realized that it simply cannot afford to antagonize Beijing over a project so dear to the hearts of the Chinese leadership, especially after antagonizing the West by intervening in Ukraine in 2014. Moreover, Russian influentials have gone even further, exhibiting a newly found support for some sort of alliance with China.

Only a few years ago Russian leaders were reluctant to even discuss an alliance with Beijing. Then-chief of the Russian presidential administration and President Vladimir Putin’s close ally Sergei Ivanov publicly said in June 2014: “I find no sense, and the Chinese side, I must admit, also finds no sense, in creating a new military alliance or union, or something like that.” However, as relations with the West hit one low after another in the wake of Russia’s intervention in Ukraine, Russian influentials began to profess a different view. As Brussels and Washington restricted trade and finance ties to Moscow to punish it over Ukraine, leaders in the Kremlin turned their gaze eastward. Russian policy-shapers began to openly entertain the idea that Moscow’s own pivot to Asia should culminate in the establishment of a formal Sino-Russian military-political alliance. For instance, in 2016 ex-chief of the Russian Defense Ministry’s international cooperation department Gen. Yevgeny Buzhinsky openly called for “truly allied relations” between Russia and China, while many Russian participants of an April 2017 meeting of Russian and Chinese experts under the aegis of the Kremlin-funded Valdai Club “came out in support of a Russian-Chinese military alliance,” according to an account of the event in Russia’s Kommersant newspaper. Sergei Karaganov, a former Russian presidential advisor who attended the event, penned an article in which he notes that “Russia and China have built allied relations de facto but not de jure”; the Russian Embassy in London has posted the article to its website. Russian influentials’ recent musings about a potential alliance with China have been welcomed by some of their Chinese counterparts. Prominent Chinese political scientist Yan Xuetong also spoke to Kommersant in favor of such an alliance: “China has half approached the status of a superpower. Therefore, this principle [of not entering alliances] is no longer in our interest,” Yan declared in a March 2017 interview. “I do not understand why Russia does not insist on forming an alliance with China.”

In addition to the Ukraine crisis, there are at least five sets of longer-term factors that lend themselves to closer ties between Russia and China, which already cooperate in such formats as the Shanghai Security Organization and BRICS. The first factor is trade. Russia is interested in selling and China in buying Russian oil, gas and arms. After overtaking Germany as Russia’s largest trading partner in 2010, China has not looked back: Its share in Russia’s foreign trade last year totaled 14.1% whereas second-place Germany accounted for 8.7%, according to the Russian customs service. Second, both countries have a vested interest in stability in Central Asia to prevent the rise of militant Islamism there. Third, the two also want to preserve their rights as veto-wielding permanent members of the United Nations Security Council. Fourth, they share a number of serious grievances vis-à-vis the Western world. Both Moscow and Beijing oppose a U.S.-led world order and some of its features in particular, like the expansion of U.S.-led military alliances and the expanding reach of U.S. ballistic missile defenses and conventional prompt-strike capabilities. They also are discontent with the U.S. dollar’s leading role in global financial markets and with “color revolutions,” which both blame on the West. Finally, Russian leaders have come to believe that the U.S. and its Western partners are in long-term decline, while China is a rising power and engaging it would pay off for Russia. As Putin has observed: “In the 21st century, the vector of Russia’s development will … toward the East.” While opposing U.S. supremacy, Putin has already publicly conceded Chinese pre-eminence, stating that his country will not dispute the Middle Kingdom’s claim to global leadership. “The main struggle now underway is for global leadership and we are not going to enter a dispute with China on this,” Putin has said.

There are, of course, factors that hinder the emergence of a Sino-Russian alliance. These include Russia’s reservations about demographic, economic and conventional military disparities in areas straddling the Russian-Chinese border that may come to threaten Moscow’s control of the Russian Far East. Russia’s share in global GDP, if measured in terms of purchasing power parity in constant dollars, rose from 2.94% in 1999 to 3.08% in 2015. In contrast, China’s share in global GDP rose from 7.14% in 1999 to 17.13% in 2015. China outspent Russia militarily by a factor of three last year, and there are fewer people living in all 27 Russian provinces east of the Ural Mountains than in Heilongjiang, just one of the four Chinese provinces bordering Russia. Another damper on closer Russian-Chinese ties is Moscow’s arms trade and robust relations with such regional opponents of China’s rise as Vietnam and India. China’s expanding foot print in Central Asia, where it has displaced Russia as the dominant economic power, has also caused frictions between Moscow and Beijing. These factors make the formation of a de jure Sino-Russian military-political alliance unlikely in the short term. However, the longer Russia remains in a state of Cold War with the West, the less Russian leaders will factor in these friction points as they decide whether to seek such an alliance as a counterweight.

A military-political alliance between a rising China and an antagonized Russia would not be in America’s interest. To prevent it, the U.S. can, of course, try to play Moscow and Beijing off one another, but such a strategy might backfire, given how close Russia and China have become economically and politically. Washington would do well instead to normalize relations with Russia in the short term—on the condition that Moscow make concerted, genuine efforts to resolve the conflicts in Ukraine and Syria on terms acceptable to key stakeholders—while continuing to maintain a constructive relationship with China. If this sort of constructive relationship could permeate the whole American-Sino-Russian triangle, that would help China and America to escape what Harvard professor Graham Allison has described as Thucydides’s trap: When a rising power threatens to displace a ruling one, the most likely outcome is war.

Simon Saradzhyan

Simon Saradzhyan is the director of Russia Matters and assistant director of the Belfer Center's U.S.-Russia Initiative to Prevent Nuclear Terrorism.

Photo credit: photo courtesy of www.kremlin.ru, shared under a Creative Commons (BY 4.0) license.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.