Looking for U.S.-Russian Cooperation? Try Asia

Among the few consistent lodestars for Donald Trump’s campaign rhetoric on foreign policy was the need to improve relations with Russia. In the short-run, any effort to reset U.S.-Russian relations can only come at the expense of U.S. allies and partners in Europe, who are most exposed to Russia’s push to establish a sphere of influence around its borders. If Trump’s team is serious about trying to fix U.S.-Russian relations without abandoning longstanding U.S. commitments to upholding the Euro-Atlantic security order, one possibility would be to look for opportunities for cooperation in the Asia-Pacific.

Unrealized Potential

As in Europe, the United States has been since 1945 the guarantor of peace and stability in the Asia-Pacific through its network of alliances. In contrast to Europe, where Russia has long opposed NATO expansion and feared U.S. containment, Moscow has traditionally supported U.S. alliance commitments in Asia, which have underpinned stability on the Korean Peninsula and dissuaded countries like Japan and South Korea from developing their own nuclear weapons while maintaining freedom of navigation that benefits Russia’s Far Eastern economy.

U.S. national security bureaucracy is structured along regional lines, and officials charged with managing U.S. interests in the Asia-Pacific generally have little familiarity with or interest in Russia.

Yet U.S.-Russian relations in Asia have long been underdeveloped. For understandable reasons, the U.S. is not accustomed to think of Russia as an Asia-Pacific power. The U.S. national security bureaucracy is structured along regional lines, and officials charged with managing U.S. interests in the Asia-Pacific generally have little familiarity with or interest in Russia, which is the responsibility of officials focusing on Europe and Eurasia.

Moreover, Russia’s political, economic and cultural centers all lie in Europe. Only around 6.3 million people live in the Russian Far East, a territory larger than the European Union. Russia plays, at best, a secondary role in Asia-Pacific institutions like APEC (despite spending upward of $20 billion on hosting the organization's 2012 summit in Vladivostok) and the East Asia Summit. The U.S.-backed Trans-Pacific Partnership, which Trump has promised to jettison, did not include Russia. To the extent Russia does play an active role in the region, it is often in close partnership with China, another country whose regional ambitions are a source of concern in Washington.

Russia nonetheless aspires to play a larger role in the Asia-Pacific. Unlike the situation in Europe, Russia is not an openly revisionist power in Asia—and its partnership with China is ambivalent enough to create opportunities for Washington to pursue some clearly defined areas of cooperation at a time when relations in Europe and Eurasia are as bad as at any time since the Cold War.

Obvious Starting Point: Korea

In particular, Washington and Moscow share a common interest in rolling back Pyongyang's nuclear program and reducing tensions on the Korean Peninsula, avoiding conflict over contested maritime territories from which neither would benefit and maintaining a pluralistic regional security environment not dominated by China.

Russia is genuinely concerned about Pyongyang's nuclear and missile programs, not to mention the possible collapse of the North Korean state.

Korea presents an obvious focus for U.S.-Russian cooperation. Along with China, Russia is one of the few countries to maintain friendly relations with both Koreas. Sharing a border with North Korea, Russia is genuinely concerned about Pyongyang's nuclear and missile programs, not to mention the possible collapse of the North Korean state, which could send large numbers of refugees across the border. Like the United States, Russia is represented in the suspended Six Party Talks on North Korea's nuclear program, meaning it already has a seat at the table should talks resume. Moscow is also deeply troubled about the possibility that Washington will deploy a missile defense shield to protect its Asian allies from North Korean rockets, giving Russia a strong incentive to work with the U.S. and others to seek concessions from Pyongyang.

Russia and China: It’s Complicated

Russia has for the most part sought to stay out of maritime territorial disputes between China on the one hand and U.S. allies and partners on the other. Since the start of the conflict in Ukraine, Moscow has begun subtly tilting China's way on these disputes, with Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov in April adopting Beijing's position that the disputes should be solved without outside (i.e. U.S.) interference. Yet Russia also has important energy and weapons agreements with Vietnam, which is contesting Beijing's claims in the South China Sea, and is holding out the prospect of an agreement with Japan, which is nursing its own dispute with China over islands in the East China Sea. A conflict in either sea could threaten Russian economic interests, and force Moscow to take sides when it has little interest in doing so.

Russian officials and analysts dislike being pulled into China's orbit. Frustration with unfulfilled Chinese promises creates an opening for the U.S. and its allies.

Russia has moved China's way on these disputes because it has little choice given the poor state of relations with the West; support for the Chinese position is Beijing's pound of flesh for bolstering Russia in its time of need.

Many Russian analysts and officials recognize that Moscow needs to be more than a stalking horse for Beijing if it wants others in the region to take it seriously. As long as Moscow believes it is locked in an existential struggle with the West, it will continue to prioritize relations with China in the region. Yet Russian officials and analysts dislike being pulled into China's orbit. Frustration with unfulfilled Chinese promises creates an opening for the U.S. and its allies to seek Russian support for efforts to maintain a more open, pluralistic vision of Asia-Pacific security.

This opportunity stems from the nature of the "arranged marriage" between Moscow and Beijing. While the two countries have many good reasons to cooperate, from trade to border security to rejection of U.S.-led democracy promotion, their relationship remains more difficult than it looks on the surface.

By mid-2016, it was clear that this tilt to China was failing to live up to Russian expectations.

Russia has sought improved relations with China for many years, but its cultivation of China accelerated with the start of the crisis in Ukraine and the imposition of Western sanctions in early 2014. The two countries rushed to complete a long-delayed agreement to build a natural gas pipeline from Eastern Siberia to China. They signed a currency swap agreement and began working on a mechanism to facilitate payments outside the U.S.-dominated global banking system. Joint military exercises increased, and Russia's tilt toward Beijing's position on the South China Sea emerged.

Yet this tilt to China has never lived up to Russian expectations. The pipeline deal remains on the drawing board, amid disputes over investment and the eventual route. Financing from China’s domestically focused banks proved disappointing. The main corridor of Beijing’s One Belt One Road is set to bypass Russia to the south, limiting Moscow’s ability to benefit from either the infrastructure itself or the transcontinental trade it will carry. Nor is Russia interested in joining the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), the Chinese-sponsored trade agreement given new life by Trump’s rejection of the TPP.

Russia’s Other Asia Interests and the U.S. Role in Shaping Them

Meanwhile, excessive reliance on China in many ways handicaps Russia’s quest to be a major player in Asia, which requires it to deepen relations with several states in East, South and Southeast Asia wary of a more powerful China. Russia’s relations with two East Asian states in particular, Japan and Vietnam, along with India, encapsulate this dilemma.

Moscow views Tokyo as a possible source of investment capable of balancing Chinese financing. Yet Japanese investment remains miniscule, largely because of Russian corruption, but also because of the unresolved dispute over the Southern Kurils/Northern Territories that the USSR seized in 1945. Under Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who will host Putin in mid-December, Japan has dangled the prospect of escape from international isolation, targeted investment in the Far East and energy cooperation as carrots to gain not only the islands but, perhaps more importantly, Russian assistance against China. Abe was also the first foreign leader to meet with President-elect Trump, and is eager to gain U.S. assent for his diplomatic initiative.

U.S. policy remains a key factor in determining whether Moscow’s Asia pivot centers on pragmatic engagement with a range of Asia-Pacific states or a partnership with China focused mainly on undermining U.S. leadership and the liberal international order.

Chinese officials have apparently been placing significant pressure on Moscow not to accommodate Abe, a development that could help explain Moscow’s recent decision to further militarize the disputed islands and downplay talk of a deal with Tokyo. Greater U.S. support for Abe’s initiative could make it more attractive to Moscow.

Similarly, Vietnam is a longstanding customer for Russian military equipment, including attack submarines that Hanoi values for their ability to defend maritime claims against Chinese encroachment. Vietnam has also granted Russian state-owned energy companies drilling concessions in disputed waters of the South China Sea. These considerations did not, however, prevent Moscow from adopting the Chinese position that these disputes should be resolved between the affected states themselves without outside (read “U.S.”) interference or from arming the Chinese navy.

Russia is trying to cultivate other partners in Asia too, especially through new arms and nuclear power deals. These include India, also a longstanding client of the Russian-Soviet defense industry with which Moscow is seeking to co-develop new weapons systems (including a fifth-generation fighter plane) and another rising power with a sense of grievance against Beijing, as well as Thailand, Laos and Indonesia.

U.S. policy remains a key factor in determining whether the focal point of Moscow’s Asia pivot is pragmatic engagement with a range of Asia-Pacific states (including U.S. allies like Japan and South Korea) or a partnership with China focused mainly on undermining U.S. leadership and the liberal international order.

Thoughts on Future U.S. Policy

Growing Sino-Russian cooperation was perhaps an inevitable consequence of the West’s efforts to push back against Russian aggression in Europe at the same time it was trying to constrain China’s territorial ambitions in the South and East China Seas. The lesson is that the U.S. should try to avoid pursuing confrontation with China and Russia at the same time or making either into a permanent foe.

Arguably, Washington has done a better job balancing its relationship with China: Even as the U.S. seeks to restrain Chinese territorial ambitions, it has managed to work with China on a range of economic issues, as well as climate change. As much as the U.S. needs to support its NATO allies and deter further aggression against Ukraine, it cannot afford to write off all hope of cooperation with Russia particularly in areas where the two sides’ interests are at least reasonably compatible.

Asia remains an untapped resource for U.S.-Russia cooperation that, especially given current tensions in Europe and the Middle East, is worth exploring. President-elect Donald Trump’s focus during the campaign on pushing back against China, if implemented, could actually provide a hook for pulling Moscow closer, allowing it to more effectively balance between Washington and Beijing.

To be sure, obstacles to U.S.-Russian cooperation in Asia remain substantial. The U.S. cannot afford to be seen making concessions to Russia while sanctions remain in place and the Minsk ceasefire agreement remains unfulfilled. Notwithstanding Russian disaffection with the fruits of its partnership with China, Beijing’s influence over Moscow remains substantial. And of course, the U.S. bureaucracy remains poorly structured to focus on Russia in an Asia-Pacific context.

Nevertheless, at a moment of increasing uncertainty and danger of confrontation, the U.S. needs to start doing something different with Russia. Perhaps it should start in Asia.

Jeffrey Mankoff

Deputy director and senior fellow with the Russia and Eurasia Program of the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

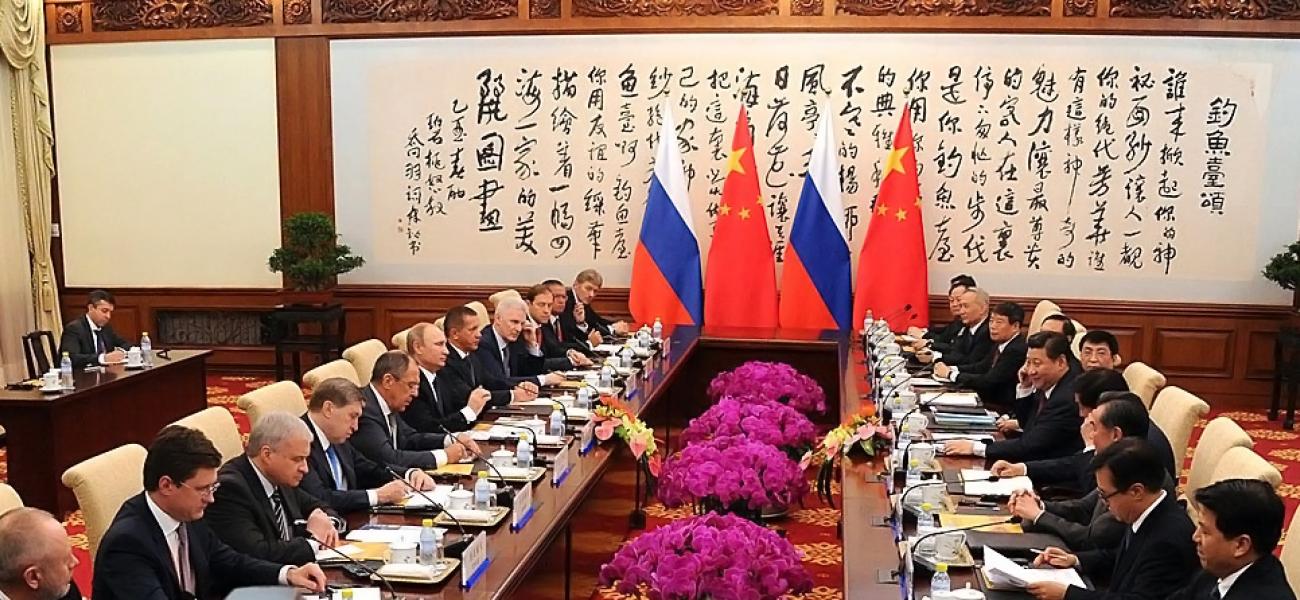

Photo shared under a Creative Commons (BY 4.0) license.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.