Negotiators, Take Heed: Whether You’re Talking With Russia or Others, New Book Is Master Class on Working Your Way to a Deal

BOOK REVIEW

“Negotiating the New START Treaty”

By Rose Gottemoeller

Cambria Press, May 2021

With a terrifying full-scale war raging in Ukraine, 2022 does not seem to be the year of the negotiator. But in the shadow of the cataclysmic changes roiling both the European and global security environments, negotiators and diplomats are, in fact, hard at work, looking for ways to make the world safer for their countries and, it is hoped, as a whole. As they do that, they might spare the time to read Rose Gottemoeller’s “Negotiating the New START Treaty.” The senior diplomat’s account of leading the U.S. delegation to forge that critical agreement is a master class in how to work your way to a deal, both with your negotiating partner and with your bosses back home. It’s also a good story.

Those readers privileged to have interacted with Gottemoeller (for full disclosure, our paths have crossed several times over the decades) will find that on the page she is much like she is in person: clear, straightforward, factual. When she offers the occasional funny aside, it often triggers a bit of a double-take (wait—did she just tell a joke?). This memoir also illustrates why she is so universally respected, admired and, yes, liked, by both colleagues and antagonists, Americans, Europeans and Russians. As Gottemoeller relates step by step what happened behind the scenes of a crucial negotiation, she cannot help but imbue the story with her genuine desire to reach the right outcome, to solve each new thorny problem. Also echoing throughout this text is Gottemoeller’s commitment to understanding perspectives different from her own, her respect for expertise and, indeed, her fundamental decency. One also gets the sense that she is an excellent manager, someone you’d want to work with and for.

While you get a real sense of Gottemoeller’s personality, if you are looking for a lot of soul-searching regarding U.S. policy and priorities, this is not the book for you. But then, New START is probably not the treaty for that, either. Gottemoeller’s attitude—that this negotiation was important, and critical to both U.S. and Russian security—reflects a pretty broad consensus in both the U.S. and Russia. And for all her many years living in Russia and working with Russians, Gottemoeller’s perspective is very much rooted in U.S. foreign policy thinking and priorities. As she herself says, this is an insider’s story.

The consensus that this was a necessary treaty was there from the beginning, and negotiators had some other advantages as well. Both the United States and Russia wanted New START, signed in April 2010, because its predecessor START treaty was expiring. Moreover, the treaty was negotiated at a time when relations between the two nuclear superpowers, while not exactly friendly, were comparatively collegial. Both countries sent consummate professionals to do the hard work, namely Gottemoeller and her Russian counterpart Anatoly Antonov—now Russia’s ambassador to Washington—and their respective teams. These were people experienced with the issues, with the other country and with their own political systems. But despite these advantages, New START was still a challenge to negotiate.

Gottemoeller relates the story in a direct, sometimes almost telegraphic style. She tells us a bit about her background and how she ended up leading the U.S. delegation. She walks us through the lead-up to the talks, and the development of her relationship with Antonov, who then headed the Russian Foreign Ministry’s Department of Security and Disarmament. She gives us a play-by-play of the negotiations themselves, taking care to explain some of the technical issues, rendering them accessible to the casual reader as well as the expert.

Some of those issues were, of course, straightforward—which weapons to limit and how much (and how) to limit them. Others were more technical and logistical: How do you keep track of the weapons themselves? How can you be confident that the other party won’t move their mobile missiles off base when an inspection approaches? How do you reassure your counterparts that a launch tube that once held nuclear missiles will no longer do so? These questions can prove complicated even after the fact: For example, although negotiators agreed to allow such conversion procedures for launch systems, Moscow would later complain that the U.S. approach to rendering submarine launch tubes unusable is reversible—something the treaty simply did not address.

And then there were the negotiating points that reflected political exigencies and unilateral security perceptions. It was crucial to Moscow that missile defenses be somehow incorporated into this treaty, even as the U.S. wanted them off the table entirely. Meanwhile, senior members of the U.S. Congress, particularly, wanted telemetry (flight test data) information to be part of the treaty verification protocols, as they had been in START, even though the terms of the new treaty made this information somewhat beside the point.

Indeed, a striking aspect of Gottemoeller’s telling is that she and her team faced as many challenges from the United States as they did from their Russian counterparts. This is therefore a book as much about negotiating with the highest levels of Washington, D.C., as it is one about negotiating with Moscow. A casual observer might even be forgiven for thinking the Americans the bigger problem—one, after all, expects challenges from the potential adversary (and Gottemoeller’s tales of Antonov’s early efforts to set her off balance, as well as of the later evolution of their working relationship, makes for fascinating reading), but why are the U.S. Congress and White House making things so hard? Aside from policy differences, Gottemoeller found herself faced with not only micromanagement but second-guessing of even the most basic concepts, such as the very idea that negotiators need to negotiate, face to face, over time. For everyone interested in questions of domestic politics and the two-level games government negotiators must play, this book offers a valuable case study, including insights from a veteran Russia hand into how this may have worked in Moscow, as well.

It is also an important case study of working under pressure, in part as a result of these two-level negotiations. Gottemoeller and her negotiating team seemed constantly pulled in all directions, as were their Russian counterparts. Gottemoeller’s (and, apparently, Antonov’s) blood pressure spiked. I was also struck by her consistent efforts to take as much of these problems as possible onto herself, to protect her colleagues even as she relied on them. And because I’ve always admired Gottemoeller as a master diplomat, I was fascinated to read of her struggles with the various personalities and demands and a bit surprised to witness her criticism, in hindsight, of her own management, largely because I found it difficult to see how anyone could have done better.

Gottemoeller was also working with a whole lot of men. One does in this line of work, although things are getting better, but the gender imbalance in these negotiations was striking. The Russian side was, not surprisingly, worse than the American, and I enjoyed learning of Gottemoeller’s quiet efforts to empower the women across the table, both by paying them extra attention and by telling Antonov point-blank that he should elevate their roles—which he eventually did. But the female names on the U.S. side were also few and far between, lending the memoir, in this sense at least, the flavor of a Tolkien novel or the first Star Wars trilogy. Also echoing the “Lord of the Rings,” the women, in some contrast to the men, seem to have been generally capable and value-additive, almost always part of the solution and not the problem. It was not Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and Under Secretary of State Ellen Tauscher who were micromanaging the negotiating team.

The memoir closes by taking us along for the ride as Gottemoeller and her colleagues advocate for the now agreed treaty on Capitol Hill and with a variety of constituencies back in the United States. This part of the story is a valuable reminder that however globally you think, you’ll likely end up having to act locally to actually get things done, even on topics as geostrategic in nature as arms control.

Gottemoeller’s memoir tells the story of one very specific treaty. It is a story rooted in its time and, as such, evokes a bit of nostalgia for a moment when Russians and Americans could sit at a table together to work for overlapping, if not fully common, goals. As I write these words, it’s far from clear when this will again be possible. Add to that the shrinking of appetites for and understanding of diplomacy even before this eventful year, and it seems quite likely that Gottemoeller’s successors (and she herself if and when she returns to government service) will find it that much harder to get to deals, arms control or otherwise, even as the world gets more dangerous, and the need for deals greater. But the experience Gottemoeller describes, including the multiple levels of negotiation and the hard work, time and expertise required, is generalizable beyond the United States and Russia, beyond that moment of over a decade past, and beyond strategic nuclear weapons. Future negotiators have their work cut out for them. They can be better prepared by studying past experiences, such as that recounted in this valuable book.

Olga Oliker

Olga Oliker is the program director for Europe and Central Asia at The International Crisis Group, leading the organization’s research, analysis, policy prescription and advocacy in and about Russia, Europe, Turkey, the Caucasus and Central Asia.

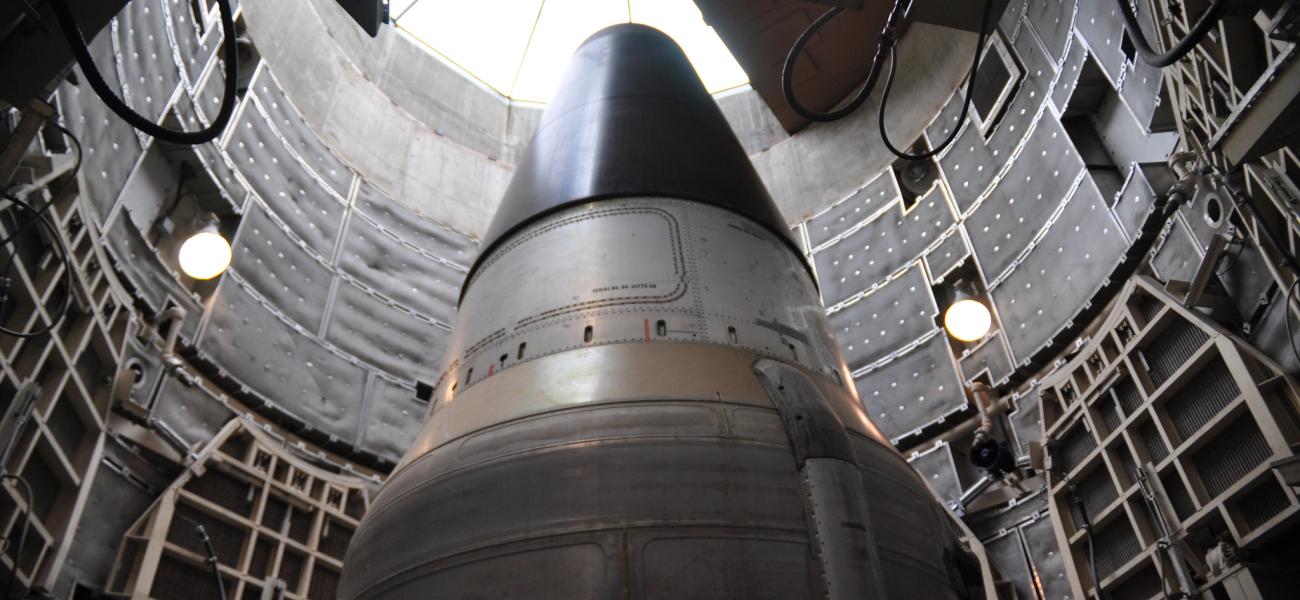

The opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author. Photo by Jonathan McIntosh shared under a Creative Commons license.