Russia’s Impact on US National Interests: Ensuring Energy Security

Editors' note: Whether there is a change of guard in the White House or not next January, the results of presidential elections traditionally offer the U.S. head of state a chance to commission a review of U.S. domestic and foreign policies. This primer is the second in a series designed to facilitate a reassessment of America’s relationship with Moscow by detailing exactly what impact Russia does or can have on each of five vital U.S. national interests, as defined by a task force co-chaired by Graham Allison and Robert D. Blackwill, and offering selected recommendations on how to best advance these interests during the next presidential term of 2020-2024. These interests are as follows: (1) maintaining a balance of power in Europe and Asia; (2) ensuring energy security; (3) preventing the use and slowing the spread of nuclear weapons and other weapons of mass destruction, securing nuclear weapons and materials and preventing proliferation of intermediate and long-range delivery systems for nuclear weapons; (4) preventing large-scale or sustained terrorist attacks on the American homeland; and (5) assuring the stability of the international economy.

Executive Summary

Energy—and the heat, light and power it provides—is the lifeblood of modern civilization. One economist called it “not just another commodity, but the precondition of all commodities,” inextricably linked with water and food security, an input for almost all goods and services that has been correlated to military might, economic growth and the well-being of citizens. Consequently, energy security is perceived to be a critical component of national security by countries diverse in culture, size and energy abundance.

Although many countries are simultaneously energy consumers and producers or exporters, they can usually be categorized as predominantly one or the other. The U.S., however, straddles the consumer-exporter divide almost equally: It is the world’s largest consumer of crude oil but also currently its largest producer, as well as the world’s largest exporter of petroleum products and the world’s third largest exporter of natural gas. This makes energy security relatively more complex in the U.S., involving significant trade-offs and juggling. Russia, meanwhile, is one of the world’s three largest energy producers and exporters and intends to sustain this position through an expansion in production and exports of oil and gas. Russia is also one of the great powers with whom the U.S. is engaged in geostrategic competition; it can and has drawn upon energy statecraft, among other tools, to try to advance its national interests, sometimes while constraining U.S. options for foreign policy. No other country better meets these two criteria—major energy producer and geopolitical near peer.

This primer strives to discern Russia’s impact on the United States’ vital interest in ensuring its energy security, which the author defines as the availability of a diverse range of energy resources that are reasonably priced and resilient to disruptions and which exhibit an acceptable level of environmental sustainability, both in the recent past and over the next five years. That impact can be summarized as follows: While Russia has a negligible effect on the availability of energy in the U.S., it exerts significant influence on U.S. gasoline prices—which, in turn, affect the U.S. economy as a whole—and it constrains the diversity of export markets for U.S. oil and natural gas. At the other end of the spectrum, Russian nuclear power, coal and renewable energy policies have minimal impact on U.S. energy security. In terms of U.S. energy systems’ resilience, Russia has not caused any known disruptions but has been accused of cyber intrusions with the potential to adversely affect U.S. energy supplies. More of the same can be expected over the next five years: The lack of meaningful structural reforms to Russia’s sanctions-hobbled economy means a continued dependence on hydrocarbon exports, while a post-pandemic recovery of energy demand will result in even fiercer competition for market share. A more detailed breakdown follows.

Availability: Russia's impact on the availability of energy to U.S. consumers is minimal. Russian petroleum—crude oil and refined petroleum products combined—accounted for less than 6 percent of the total imported in 2019 (about the same as Saudi Arabia’s but incomparably less than Canada's 48.5 percent), and less than 1.5 percent of U.S. energy consumption in total. Russian natural gas made a high-profile appearance in the U.S. in 2018, but that was a stopgap measure; overall that year Russian gas made up less than 0.5 percent of U.S. imports. Russian coal imports, meanwhile, accounted for about 0.01 percent of U.S. coal consumption in 2018. Russian uranium for use in U.S. nuclear power plants made up 13 percent of total U.S. purchases of the fuel in 2018, but even that accounts for only a bit more than 1 percent of total U.S. energy consumption (and the problems faced by the United States’ own nuclear industry have little to do with Russia’s nuclear energy exports).

Diversity: Russia’s impact on the diversity and sources of the U.S. energy mix is minimal (see above on availability); Russian energy exports, however, play a major role in constraining the diversity of export markets for U.S. oil and gas, and to a much lesser extent coal. This trend is likely to persist as energy exports and revenues contribute significantly to Russia’s coffers: According to a JP Morgan report, in 2018 oil revenues made up 41.5 percent of federal government revenues in Russia but less than 3 percent in the U.S., excluding corporate income tax.1

Energy prices: Russia has a significant impact on the affordability of gasoline for U.S. consumers since the global price of crude oil makes up over half the retail cost of domestically sold gasoline, which in turn affects the economy overall. The price of oil is partly shaped by Russia’s decisions on the volume of oil supply and export through its shared governance of OPEC+ and this also impacts the profitability of U.S. oil companies; this impact can probably be mitigated, however, through U.S. diplomacy with Saudi Arabia. In the gas sector, Russia’s pipeline gas exports to Europe and China put downward pressure on the price of U.S. exports of liquefied natural gas, or LNG. (The reverse—that U.S. LNG exports put downward pressure on Russian pipeline gas prices—is also true, albeit to a relatively smaller degree.)

Resilience to disruptions: Russia has a minimal impact on disruptions of physical supplies of energy sources to U.S. power plants and refineries (see availability and diversity above). It is also not responsible for the relative lack of attention paid to U.S. strategies, including demand management, meant to increase resilience to energy disruptions. Russia and its proxies, however, have been classified as major perpetrators of cyberattacks, including breaches of corporate networks with access to critical infrastructure such as power grids and nuclear facilities. U.S. energy systems have so far been resilient.

Environmental sustainability: The struggle for environmental sustainability plays out in parallel in the U.S. and Russia. As major producers of hydrocarbons, both countries are likely contributing to the accelerating pace of climate change and both have suffered as a result, with record-breaking heat waves, raging peat and forest fires and, in Russia’s case, dangerous accidents on thawing permafrost. The U.S. has done more than Russia to increase the uptake of renewable energy and these efforts will not meet with much Russian resistance since renewable energy exports are absent from Moscow’s energy strategy. Russia has allegedly funded some U.S. anti-fracking groups in an attempt to roll back global competition from U.S. shale. In the case of coal, its decline in the U.S. has to do with fuel-switching due to the economics of cheaper shale gas, rather than with Russian influence.

Aside from energy security per se, Russia and the U.S. have at times wielded “energy diplomacy” in pursuit of their respective foreign policies, now with an added element of commercial competition. This creates new tensions that need managing. For example, while Washington sees Moscow as a challenge to U.S. prosperity and security, and a rival intent on undermining U.S.-Europe relations, some U.S. allies in Europe see Russian energy as an ingredient in their own prosperity. Likewise, as the U.S. tries to maintain the difficult balance between low gasoline prices for consumers and strong profits for oil companies, it will have to engage in sophisticated ways with both Saudi Arabia and Russia itself. China, too, will continue to be a significant player in the energy-diplomacy equation: While the U.S. is unlikely to replace Russia as a key energy supplier to China in the next five years, neither does it want to drive its two adversaries closer together.

Ultimately, for true energy security, the U.S. will not be able to go it alone, no matter how much oil and gas it produces. In the case of hydrocarbons this is due to the quirks and logistics of U.S. oil refining, and in the case of their main alternative, renewable energy, this is due to the globalized nature of supply chains.

Defining US Energy Security

Energy security is a nebulous concept. The term has at least 83 definitions, is quantified using more than 60 different indices (with wide variation in the number of indicators used per index) and varies depending on scale, fuel type, time horizon and geographical location. A leading energy economist once quipped that “if you cannot think of a reasoned rationale for some policy based on standard economic reasoning then argue that the policy is necessary to promote ‘energy security.’”

U.S. officials and policy experts are not immune to this multiplicity of definitions. Since the 1970s, all U.S. administrations have prioritized energy security, but the phrase has meant different things: energy self-sufficiency, ending all oil imports, eliminating or reducing imports only from the Middle East, minimizing dependence on imports and even entirely weaning the country off oil. As a presidential candidate, Donald Trump hearkened back to that history, declaring in 2016 that the U.S. will “accomplish complete U.S. energy independence,” no longer needing “to import energy from the OPEC cartel [Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries] or any nations hostile to our interests.”

Indeed, different government agencies and think tanks focus on different aspects of energy security. According to the U.S. Congressional Budget Office, for example, energy security in 2012 was narrowly defined as the “ability of U.S. households and businesses to accommodate disruptions of supply in energy markets.” For the American Security Project think tank, on the contrary, energy security involves activities far beyond U.S. borders and even outside the realm of energy per se—namely, it is the ability of Washington “to act in its foreign policy independently of how it uses energy domestically.” In 2017, the U.S. Department of Energy noted that, “for the last 40 years, energy security in the United States has focused on decreasing the nation’s dependence on foreign oil,” but the time had come for a new, modern, holistic reconceptualization. DoE’s “21st-century framework,” derived from the G7 meeting of May 2014, has seven points: transparent, competitive markets; diversification, including encouragement of indigenous energy sources; moving toward a low-carbon economy; enhancing energy efficiency; promoting clean, sustainable energy; improving energy systems’ resilience; and establishing emergency response systems.

For the purpose of this primer, and based on existing literature on the topic, energy security will be defined, as stated above, as the availability of a diverse range of energy resources that are reasonably priced and resilient to disruptions, and which exhibit an acceptable level of environmental sustainability. In light of the United States’ dual role as a major consumer and major producer of energy, the proposed definition encompasses considerations of both supply security (for consumers) and demand security (for producers/exporters). Each component of the definition is sure to engender some debate—i.e., what constitutes adequate diversity or reasonable prices and profits or environmental “acceptability”—but the definition overall should hold true for the foreseeable future.

Continuity and Change in US Energy Security

Before delving into the impact Russia can have on U.S. energy security, it is worth considering the changes that have taken place in this sphere in the past two decades. Most significantly, they include the so-called shale revolution and its impact on U.S. energy production, exports, jobs and foreign policy, as well as the lifting of the U.S. ban on crude oil exports in December 2015. With energy producers now able to extract previously inaccessible hydrocarbons, the United States has become the world’s most energy-abundant country, while remaining its largest consumer of energy as well. Though the traditional focus of U.S. energy policy on oil has been officially updated to include all forms of energy, oil and gas do still get priority. These trends have also expanded the idea of “energy prices,” which now presumes not just affordability for consumers but profitability for producers and exporters. While the new indigenous supplies have improved most aspects of U.S. energy security, they have not eliminated the country’s vulnerability to price and supply volatility in global energy markets. This is particularly true of crude oil, Russia’s largest export. The U.S. will continue to import crude oil even if it becomes a net exporter of petroleum products, as expected within the next few years, due to the particularities of its refineries and oil-related logistics. Meanwhile, the current administration has been much more ambitious than its predecessors not only in pushing U.S. oil and gas to international markets but in using them, or the confidence they lend, to pursue geopolitical goals. These shifts are underpinned by a relatively new narrative about the promising future of the hydrocarbon industry and by the rise of “neomercantilist” practices, which include resource nationalism in Russia and the global reach of Chinese state-owned strategic enterprises, but have also been embraced by the Trump administration.

To begin, it bears repeating that availability and reliability, as well as affordability, have long been foci of U.S. energy security. This policy perspective emerged from several historical factors, among them: a wave of nationalizations after the 1950s that shifted control of oil reserves from international oil companies headquartered in the U.S. and Europe to host governments; the Arab oil embargo of 1973; and the “peak oil” narrative that emerged in the late 1990s, which predicted that the world would start running out of fossil fuels early this millennium but was discredited with the rise of new technologies. U.S. energy policy has focused on increasing indigenous supplies of energy resources, in particular oil, since the 1970s. Policies included opening up new areas for oil drilling in Alaska and the Gulf of Mexico, banning exports of crude oil to maximize domestic availability, creating Strategic Petroleum Reserves to hedge against supply disruptions and increasing the use of oil alternatives such as nuclear energy to generate electricity. These were complemented by overseas engagements—through military presence, direct investments and treaties—to encourage unrestricted energy flows from the Persian Gulf, the post-Soviet region and the Americas. Demand management, such as fuel economy standards for light vehicles and energy conservation, has played a relatively less significant role in U.S. energy security policies.

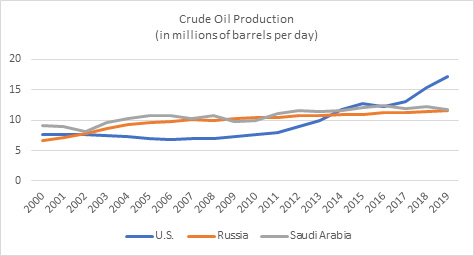

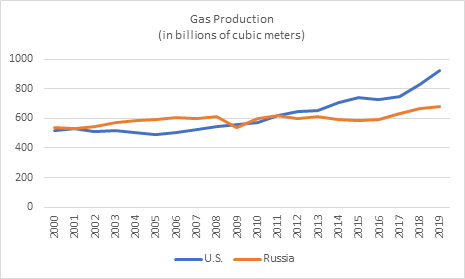

In the time that Vladimir Putin has been Russia’s leader, the United States’ significance as an energy producer has increased immensely, particularly when it comes to fossil fuels, which make up 80 percent of the world’s primary energy consumption. The U.S. has the largest volume of recoverable oil and the ninth largest proven oil reserves in the world. In 2017, already the top producer of petroleum products thanks to its huge oil-refining capacity, the U.S. overtook Saudi Arabia to become the largest crude oil producer as well; according to BP, it accounted for 17.9 percent of global production in 2019 (see Figures 1 and 2). U.S. shale oil alone—which went from 6 percent of total U.S. oil production in 2000 to over 60 percent in 2019—accounted for an impressive 6.2 million barrels per day (mbpd) or 60 percent of the increase in worldwide oil-supply growth between 2008 and 2017. U.S. shale gas has enjoyed an equally impressive rise, accounting for 75 percent of total U.S. gas production in 2019 and driving down prices so much that gas has replaced coal as the country’s fuel of choice for electricity generation (38 percent vs. 23 percent, respectively). The U.S. surpassed Russia in 2011 as the world’s largest natural gas producer, with one quarter of global production, and the fourth largest gas reserves. In addition to covering more than 90 percent of its own domestic gas consumption, the U.S. has been a net gas exporter since 2017, competing with Russia on global markets. (U.S. LNG terminals originally built to receive imports of gas were subsequently reconfigured to export it.) The United States likewise has the world’s largest reserves of coal. And over the past decade national energy policy has continued to increase access to the indigenous energy resources available for exploration, extraction and production.

Figure 1: Crude oil production in the U.S., Russia, and Saudi Arabia

Source: BP Statistical Review 2020

Figure 2: Natural gas production in U.S. and Russia

Source: BP Statistical Review 2020

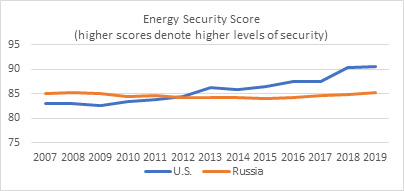

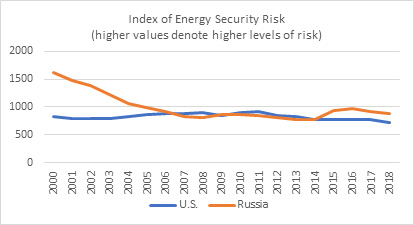

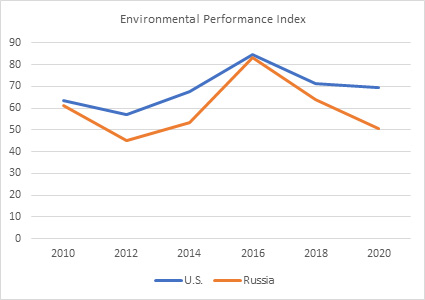

By any of the available indices, this growth in hydrocarbon production—underpinned by a regulatory environment conducive to shale resources and supported by infrastructure build-out—has improved U.S. energy security; Russia’s, meanwhile, has flagged or flatlined. According to the World Energy Council, the United States has been more energy-secure than Russia since 2012, and the Global Energy Institute rated the U.S. as the most energy-secure among the 25 largest energy-consuming countries in 2017 and 2018, up from 11th place in 2008 (Figures 3 and 4). The sustainability aspect of U.S. energy security has also improved, albeit slowly, according to Yale University’s Environmental Performance Index (Figure 5), with the decline since 2016 resulting from a trade-off with other elements of energy security—namely, availability, diversity and affordability.

Figure 3: Energy Security Score: U.S. and Russia

Source: World Energy Council

Figure 4: Index of Energy Security: U.S. and Russia

Source: Global Energy Institute, International Index of Energy Security Risk 2020

Figure 5: Environmental Performance Index, 2010-2020

Source: Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy

Although the U.S. is closer to achieving energy self-sufficiency today than in the past 70 years, its new-found “energy superpower” status belies the fact that the United States continues to import more petroleum—crude oil and petroleum products combined—than it exports, and this state of affairs is likely to persist for some time due to technological and regulatory factors. The world’s two other top oil producers, Russia and Saudi Arabia, on the contrary, export far more than they import: Their 2019 net exports of petroleum totaled 8.9 mbpd and 8.2 mbpd, respectively, while the figure for the U.S. was -1.1 mbpd (see Figure 6). Since 2016, three-quarters or more of total U.S. petroleum imports are accounted for by crude oil, even as U.S. exports of crude oil rise.

Figure 6: U.S., Russian and Saudi exports/imports of crude oil and oil products (in mbpd)

Source: BP Review of World Energy, 2018, 2019 and 2020

|

|

U.S. |

Russia |

Saudi Arabia |

|

2016 Exports of crude oil Exports of oil products Imports of crude oil Imports of oil products Net exports |

0.55 4.32 7.85 2.2 -5.2 |

5.45 2.90 0.003 0.03 8.65 |

7.52 0.995 n/a 0.091 8.46 |

|

2017 Exports of crude oil Exports of oil products Imports of crude oil Imports of oil products Net exports |

0.943 4.91 7.97 2.18 -4.36 |

5.48 3.5 0.013 0.19 8.78 |

7.18 1.15 n/a 0.142 8.26 |

|

2018 Exports of crude oil Exports of oil products Imports of crude oil Imports of oil products Net exports |

1.85 5.20 7.77 2.17 -2.8 |

5.52 3.56 0.01 0.20 8.9 |

7.37 1.27 n/a 0.23 8.3 |

|

2019 Exports of crude oil Exports of oil products Imports of crude oil Imports of oil products Net exports |

2.77 5.25 6.80 2.30 -1.08 |

5.75 3.44 n/a 0.20 8.91 |

7.20 1.20 0.001 0.24 8.16 |

Note: “n/a” denotes less than 0.0005 mbpd

This inability of the U.S. to wean itself off imported crude arises for two reasons, both connected with refining. First, major refineries along the Gulf coast are configured to process heavy, sour grades of oil from the Middle East, Canada and Mexico; the refined oil products are then consumed domestically or sold overseas. To overhaul refineries to process light, sweet shale oil from U.S. fields would be an expensive undertaking, especially amid uncertainties about the shale boom’s sustainability in today’s “lower-for-longer” global oil-price environment. The second reason that crude oil imports will continue stems from logistical hurdles that make it expensive to transport shale from Texas to suitable refineries on the northeastern coast. A 1920 law, the Merchant Marine Act, also known as the Jones Act, mandates that shipments between two U.S. ports be on U.S.-built, U.S.-manned, U.S.-owned vessels. The shortage of such ships means it can cost northeastern refineries about one-third as much to ship light crude from Saudi Arabia or Nigeria as from Texas. Thus, even if the U.S. becomes a net exporter of petroleum—as it was expected to in 2020, for the first time since 1953, before the coronavirus-related drop in demand postponed that achievement by a few years—it will continue to need imported crude oil. (Repealing or amending the Jones Act may change this, but it would spell big trouble for the U.S. shipping industry.)

The United States’ continued reliance on crude imports means that the country remains susceptible, albeit less than previously, to price volatility in the global market—a dynamic that Russian policies can certainly affect. A 2019 study noted that a 10-percent increase in the global price of oil could trigger a decline in U.S. GDP between 0.06 percent and 0.29 percent—roughly half the decline that same 10-percent increase could cause from the early 1970s to the early 2000s.

Caveats notwithstanding, the new U.S. energy abundance is forcing policymakers to look at energy prices in new ways, trying to balance the needs of consumers and energy companies. On one hand, low gasoline prices are generally regarded as a boon to U.S. economic growth because they free up discretionary spending on other goods and services. According to one study, every 1-cent decline per gallon in gasoline prices frees up $1.1 billion in spending over the course of a year. The country’s current-account deficit also benefitted from the shale boom, with expenditure on crude oil and natural gas imports dropping to 0.2 percent of GDP in 2019 compared to about 1-2 percent in previous decades (see Figure 7). On the other hand, the growing significance of the oil and gas industry to the U.S. economy have muddied the commitment to low-cost gasoline and, by extension, to keeping down crude oil prices, which accounted for 59 percent of prices at the pump, on average, in 2010-2019. Trump, for instance, played an indispensable role in facilitating a new OPEC+ agreement in April 2020 to reduce oil supply from over 20 countries and hence increase the price of crude oil. This is at least in part because the oil and gas sector contributes directly and indirectly to 10.3 million jobs and nearly 8 percent of the country’s GDP, up from less than 1 percent of GDP in the late 1990s and 3 percent as recently as 2014. In short, although analyses by Moody’s and others conclude that low oil and gasoline prices are a net positive for the U.S. as a whole, debates will continue about balancing affordability for consumers with profitability for oil and gas companies.

Figure 7: Oil and Gas Import Expenditures

Source: Global Energy Institute, Index of U.S. Energy Security Risk

|

Year |

Imports as % of GDP, annual average |

Imports in billions of dollars, annual average |

|

1970-1979 |

0.45 |

$93 |

|

1980-1989 |

1.43 |

$117 |

|

1990-1999 |

0.8 |

$92 |

|

2000-2009 |

1.75 |

$282 |

|

2010-2019 |

1.05 |

$187 |

|

2020-2029 (projected) |

-0.3 |

-$83 |

Last but not least, America’s new-found energy wealth has broadened U.S. foreign policy options once constrained by import dependence and has revived the pursuit of “energy dominance” through exports. This applies not only to oil but to gas and is aligned with the Trump administration approach variously labeled as mercantilist nationalism, neo-mercantilism, resource nationalism or simply protectionism. It represents the view that the zero-sum, transactional rules of the market extend into international politics, leaving no room for multilateral agencies, international alliances or consensual regulations if they act as a constraint on U.S. sovereignty. As recently as 2017, three leading Trump officials declared the aim of building a “self-reliant and secure nation, free from the geopolitical turmoil of other nations that seek to use energy as an economic weapon,” echoing previous administrations’ concerns not just about import dependence—long the Achilles heel of U.S. energy security—but dependence on insecure or unreliable producers like Saddam Hussein’s Iraq or Hugo Chavez’s Venezuela. By May 2019 Trump was casting the geopolitical windfall from shale oil and gas as valuable in terms of offense as well as defense, declaring that “by reducing our dependence on foreign sources of energy we have dramatically increased our power to confront our adversaries, support our friends and fight for our interests.”

Tensions with Iran provide one example: Early this year the availability of shale-powered U.S. exports largely muted oil markets’ response to the United States’ assassination of Iran’s top general, whereas the 1979 Iranian revolution had driven up U.S. gasoline prices by 120 percent. Similarly, the decline in U.S. import dependence allowed Washington to intensify sanctions on post-Chavez Venezuela in 2019: U.S. refineries were able to source cost-effective alternatives to Venezuelan oil since the latter accounted for only 6 percent of U.S. imports in 2018, down from an average of 20 percent in the 1990s and 10 percent in the 2000s. Energy as both statecraft and a source of economic growth are, in fact, throwbacks to an earlier era when the U.S. was a leading producer of oil in the world. For instance, American investment in energy infrastructure in Europe and in former European colonies in Asia and Africa helped to counter growing Soviet influence during the Cold War. The resumption of energy statecraft, however, will continue to generate controversy—both as a manifestation of American unilateralism and due to the largely privately owned structure of the U.S. oil and gas industry, which traditionally prioritizes price signals over foreign policy interests.

Russia’s Impact on US Energy Security

As noted above, Russia’s impact on U.S. energy security reflects Russia’s stature in global energy markets, as well as the broadly adversarial relationship between the two Cold War-era rivals. Moscow’s policies affect energy prices for U.S. consumers and producers, somewhat constrain the diversity of U.S. export markets and could potentially, via cyber interference, test the resilience of U.S. energy systems to disruptions. While both countries have hydrocarbon dependencies that do not bode well for environmental sustainability, Russia has only a marginal impact on the availability of the top three fuels in the U.S. energy mix—oil, gas and coal—and only a slightly bigger impact on supplies of uranium for U.S. nuclear power plants. But its decisions on oil production and export can strongly impact prices worldwide, including the affordability of U.S. gasoline, which in turn affect the U.S. economy as a whole. And just as the flipside of affordability for consumers is profitability for companies invested in energy, so too can Russia impact both. Russia’s oil, gas and uranium exports enable it to compete vigorously with the U.S. in those sectors. They also pose diplomatic challenges for Washington, especially in Europe where Russian gas and nuclear-energy activities abound. Thanks to its energy wealth, Russia is able to cooperate with traditional U.S. partners like Germany, which still regards Russian gas as a prudent choice in its energy mix, and Saudi Arabia, on the stability of the global oil market. In terms of resilience, thus far U.S. energy systems have held up well, but there is worry about the possibility of cyber-related disruptions caused by Russian actors.

For context, it is worth pointing out that Russian and Soviet energy supplies have long been perceived as a danger to U.S. geopolitical interests, particularly in Washington’s relations with European allies. (There were periods when Russian oil was viewed as a useful counterweight to Middle Eastern supplies but these were short-lived.) During the Cold War, the U.S. saw rising levels of Soviet oil and “red gas” exports to Europe as threats to the anti-communist unity of the transatlantic alliance. Two concerns were—and continue to be—paramount: European susceptibility to Moscow’s influence due to dependence on Russian energy and European vulnerability to disruptions of Russian energy supplies. In 2006, prompted by Russia’s repeated suspensions of gas exports (usually as fallout from disputes with Ukraine), U.S. Sen. Richard Lugar even proposed that NATO update its role to include the protection of member-states’ energy security from Russian actions. More recently, after Moscow’s military intervention in Ukraine in 2014, U.S. lawmakers lent bipartisan support to energy-related sanctions on Russian interests—including gas pipelines, financing for future oil and gas projects and joint projects with American energy companies in the Arctic.

Under the Trump administration, this wariness and the leveraging of energy in foreign policy have become intertwined with economic rivalry as well: Since the U.S. shale boom, Russia’s energy sales to Europe have become competition for growing U.S. exports of LNG, and this tension sometimes rings out in the administration’s diplomacy. In 2019, for example, two senior U.S. Department of Energy officials framed U.S. LNG as “freedom gas” that can give “America's allies a diverse and affordable source of clean energy.” This message seems aimed chiefly at Central and Eastern European, or CEE, countries, many of which have relied on Russia for 50-100 percent of their energy supplies. In 2017, Trump told CCE regional leaders that America is “committed to securing your access to alternate sources of energy, so Poland and its neighbors are never again held hostage to a single supplier of energy”; later that year, Lithuania reportedly became the first ex-Soviet republic to buy U.S. LNG and a Polish state-owned energy company signed a five-year import deal for U.S. LNG, despite its higher cost at the time than Russian pipeline gas. By 2018 the U.S. had locked horns with NATO ally Germany over gas purchases and Russia’s planned Nord Stream 2 pipeline, which would bypass Poland and Ukraine; the row has escalated as far as a U.S. threat of sanctions against Germany. (The U.S. announced in mid-2019 that 1,000 troops would soon be redeployed from Germany to Poland to strengthen NATO’s eastern border.) The linkage between U.S. energy exports and geopolitics has even emerged at the level of an individual state. In April, Republican Sen. Ted Cruz of Texas—where the oil-and-gas sector accounted for nearly one-third of the state’s economy in 2018—described Russia’s part in the recent oil price war with Saudi Arabia in starkly geopolitical terms: “We know Russia is our enemy. They act like our enemy. We treat them like our enemy.”

To complement this primer’s analysis of Russia’s impact on different components of U.S. energy security, this section will examine that impact by fuel type and a brief discussion of cyber security.

Oil

As one of the world’s top three oil producers, Russia impacts U.S. energy security in two main ways: by competing for export markets, thus limiting their diversity for U.S. exporters, and by affecting global energy prices through its decisions on the amount of oil it puts on the market. As noted in the executive summary, Russian petroleum accounted for only 5.7 percent of U.S. imported petroleum in 2019 and less than 1.5 percent of U.S. energy consumption overall. (Russia’s impact on oil production also affects the natural gas sector, discussed below.) Beyond the realm of energy security per se, Moscow can act as a spoiler in U.S. plans for enacting foreign policies that are linked to oil. Russia regards the oil sector as strategically important: Oil, on average, accounted for 41.5 percent of Russian federal government revenues and 44 percent of total exports between 2016 and 2019. Unsurprisingly, Russia’s latest Energy Strategy, approved in June 2020 for a 15-year period, places a premium on increasing the production and export of petroleum. While these dynamics will persist in the short and medium term, future constraints on Russian oil production may blunt Russia’s impact on U.S. energy security in the longer-term.

U.S. and Russian oil producers are competing for market share in Europe and China. Europe is the largest market for U.S. oil exports after South and Central America. U.S. oil exporters increased their European market share from 5.4 to 9.5 percent between 2016 and 2019. This pales beside Russia’s 35.4 percent share in 2019, but it does suggest that U.S. (and Iraqi) oil exporters have taken some market share away from Russia—at 38.1 percent in 2016. This became possible in part thanks to the OPEC+ cap on Russian oil production in place since 2017 (see discussion below). Going forward, U.S crude oil exports will continue to face stiff competition in Europe from Russia and other exporters, including newcomers like Guyana and Brazil. Conversely, in terms of oil product exports the U.S. should be able to comfortably retain its position as the continent’s second largest supplier after Russia. In China, meanwhile, Russia has become one of two key suppliers to the world’s largest importer of oil, whose demand single-handedly fueled 80 percent of global oil demand growth in 2019. That year Russian crude oil accounted for 15.3 percent of China’s imports, just behind Saudi Arabia’s 16.4 percent. U.S. petroleum exports to China lag far behind Russia’s but recorded breakneck growth of 76 percent between 2017 and 2018, prior to the U.S.-China trade war. U.S. oil exports are expected to grow significantly over the next few years in view of China’s commitment to purchase up to $52.4 billion worth of U.S. energy to reduce the bilateral trade deficit, rein in the trade war and prop up its fragile post-coronavirus economic recovery. The U.S., however, is unlikely to supplant Russia’s importance to China as an energy supplier in the next five years. State-owned Rosneft, Russia’s largest oil company, accounting for 40 percent of total oil production, is contractually committed to deliver 600,000-700,000 bpd annually until 2030 (followed by reduced levels until 2035) as repayment for a series of loans from Chinese oil companies. Moreover, unlike U.S. oil exports to China, most of Russia’s oil is delivered via overland pipeline; this allows China to diversify away from its reliance on seaborne cargos, which make up almost three-quarters of total imports and are potentially vulnerable to interdiction by America’s superior naval forces.

The global market share of Russian oil exports far exceeds that of the U.S. and this will not change over the next few years for several reasons: World oil demand has been battered by coronavirus-induced restrictions and is not expected to recover until 2022 at the earliest; Russia can better weather sustained low oil prices than U.S. oil companies due to a lower break-even price and state support; and the financial turmoil in the U.S. oil industry that has already engulfed 57 upstream and oilfield services companies in bankruptcy proceedings since January 2020 will affect output and exports. How the restructuring and consolidation of the U.S. oil industry plays out will bear watching.

The second way in which Russia affects U.S. energy security is through its impact on energy prices via governance of the oil market as a member of OPEC+. Since December 2016, the level of compliance among OPEC+ members with decisions on oil-output levels has contributed to changes in the global price of oil. For instance, when the OPEC+ pact was in force, the average West Texas Intermediate (WTI) benchmark price for U.S. oil was $50 per barrel in 2017, $65 in 2018 and $57 in 2019. In April 2020, however, when OPEC+ producers were free to pump at will because of a dispute between Russia and Saudi Arabia, the WTI price ranged from a high of $28 to a low of -$37.[1] The resulting job losses and bankruptcies in the oil sector alone are a stark reminder of how the fortunes of U.S. oil companies remain vulnerable to decisions by foreign countries, including Russia. The same applies to the affordability of gasoline, another key consideration for energy security and U.S. economic growth. Since the price of crude oil, and in particular the Brent crude oil benchmark, accounts for over half the gasoline price at the pump, Russia’s decisions on oil production and export play a large role. Realizing that most U.S. shale companies need an oil price of more than $50 to be profitable, OPEC+ is determined to keep prices within the $40-to-$50 range. While Saudi Arabia can usually be induced to align its oil supply decisions with U.S. interests—as demonstrated during the Persian Gulf War of 1990 and negotiations for the new OPEC+ agreement this year—the same cannot be said of Russia. This vulnerability underlines that U.S. production alone will not guarantee energy security but that it should be complemented by diplomacy, including the maintenance of the U.S.-Saudi relationship.

Over the longer term, prospects for the Russian oil industry are shaky. Studies published prior to the new OPEC+ agreement indicate that Russian oil production will start to decline within the next five years. Reasons for this include lower productivity of ageing oil fields as well as the continuation of European and U.S. sanctions that have limited technology import and financing to develop unconventional and Arctic oil fields. Russia’s declining but still large production and export volumes will continue to influence oil markets and U.S. energy security after 2030, but less sharply than is currently the case.

Thanks to its oil supplies, Russia can also diminish—or, theoretically, enhance—the effectiveness of the United States’ deployment of energy statecraft. The escalation of U.S. pressure on Venezuela since 2015—when Washington declared the country to be a threat to its national security—is a case in point. After the U.S. imposed crippling sanctions in 2019 against the sale of Venezuela’s oil, which accounted for 95 percent of the country’s export revenues, trading units associated with Russia’s Rosneft were able to undermine them. They bought, marketed, shipped and sold to buyers in Asia up to two-thirds of Venezuela’s crude oil, or double the amount before sanctions. Rosneft has since divested its Venezuela operations to avoid new U.S. sanctions on its trading arms; ironically, however, the United States’ Venezuela sanctions resulted in an uptick in U.S. imports of Russian hydrocarbon products by refineries to compensate for the loss of Venezuelan inputs. In the first six months of 2020, U.S. imports of Russian petroleum were 22 percent higher than the same period last year; they included around $150 million worth of products originating from a Russian refinery owned by the wife of a Ukrainian businessman sanctioned by the U.S. for his close ties with Putin. Although the volume of Russian petroleum exports to the U.S. may register a 25 percent increase over 2019 levels, this is not cause for concern in terms of diversity and availability given the relatively minor role it plays in total U.S. imports of petroleum (5.7 percent in 2019).

Russia’s influence on U.S. energy statecraft outside of the deployment of sanctions is also noteworthy. Since 1992, U.S. energy diplomacy in the former Soviet Union has aimed at encouraging the creation of new export routes outside the control of Russia to strengthen the sovereignty of weaker, ex-Soviet energy producers. Successful examples included the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline for Azerbaijani and Kazakh oil, the consortium for which included three U.S. oil companies, and the Kazakhstan-China pipeline. Nevertheless, 85 percent of Kazakh oil still transits through Russian territory via partly Russian-owned pipelines.

Gas

Russia and the U.S. have long been the two largest gas producers in the world, with Russia dominant in Europe and the former Soviet Union, and the U.S. preeminent in North America. Since 2016 the falling costs of LNG-related infrastructure and a surplus of U.S. gas thanks to the shale revolution have not only kept the domestic price of natural gas and electricity low for households and industry but have also encouraged U.S. gas exporters to venture into non-traditional markets in Europe, Turkey, Japan, South Korea and China. Consequently, U.S. LNG exports make up an expanding proportion of total U.S. natural gas exports, growing from 6.8 to 38.7 percent between 2017 and 2019. Russia’s heft as a gas exporter—including its established presence in Europe and its pipeline exports to China, which, as with oil, provide an alternative to sea routes—is a major, but not the only, factor limiting sustained growth in market share for the U.S. Competition between U.S. and Russian gas exporters is additionally colored by geopolitical considerations on both sides. (As mentioned in the executive summary, a tanker brought Russian LNG to the U.S. in 2018, causing quite a stir in the media, but those supplies were a stopgap; overall that year Russian gas made up less than 0.5 percent of U.S. imported gas.)

U.S. and Russian gas exporters keenly compete for customers and market share in Europe, where gas import dependency is set to rise from an already high 77.9 percent in 2018 to almost 90 percent by 2030. This rising gas dependency stems from falling indigenous gas production in the Netherlands together with reliance on gas-fired power plants to provide system stability as intermittent supplies of solar and wind power in Europe’s energy mix gradually increase. Russia boasts unrivalled structural advantages for imports of natural gas by Europe and will continue to defend its position as the EU’s top supplier given the significance of European gas sales to Russian state revenue. These advantages include the relatively low cost of Russia’s gas (lower than all competitors bar Qatar and Nigeria), its extensive network of gas pipelines, geographical proximity (which, in turn, begets fast delivery times), long-term contracts that lock in gas sales and decades of experience in the region. In 2018, Russia accounted for 40 percent of the EU’s gas imports; its 171 billion cubic meters (bcm) of exports to the EU that year—pipeline and LNG combined—outstripped the U.S.’s 3.5 bcm in LNG exports by a factor of almost 50. Russia’s European gas sales accounted for nearly 70 percent of the revenues earned in 2018 by Gazprom, the state-owned giant that has a monopoly over pipeline gas exports from Russia; the company’s sales accounted for 5 percent of the country’s GDP that year, according to Reuters.

Although U.S. gas exporters are relative newcomers to the European gas market, it is a key market for them, with Europe’s share in U.S. LNG exports increasing from 14.9 percent in 2017 to 38.5 percent in 2019. This growth is largely driven by economics. The glut of domestic shale gas has driven down prices of U.S. natural gas to under $2 per million British thermal units, or MMBtu, with the result that it is extremely competitive with traditionally cheaper Russian pipeline gas. Between January and June 2020, for example, Gazprom recorded an 18 percent decline in gas sales to Europe even though gas demand there fell only by 6.5 percent; customers on long-term contracts such as Turkey turned to less costly U.S. LNG even at the risk of financial penalties payable to Gazprom.

Russia challenges U.S gas exports to Europe through its competing interest of maintaining or, better yet, expanding its foothold in European gas markets, as indicated in its Energy Strategy. A case in point is Nord Stream 2. A report by the consultancy Wood MacKenzie highlights that the pipeline’s completion will increase Russian gas supply to Europe at the expense of LNG. Constrained LNG exports will in turn result in more downward pressure on already low U.S. natural gas prices and cause revenue losses of up to $5 billion for U.S. gas producers. Russia’s financial challenge to the U.S. is compounded by what some influential U.S. officials and policy shapers regard as Moscow’s geopolitical strategy of using its gas to “blackmail” or keep Europe dependent on Russia and to corrupt European decision-makers, political parties and media. The U.S. imposed sanctions against firms, including European ones, involved in completing Nord Stream 2 through the Protecting Europe’s Energy Security Act in December 2019. At the same time, there are alternative proposals for the U.S. to undercut Russia’s pipeline challenge by supporting the EU’s financing of additional regasification terminals in Europe.

Apart from its direct impact on U.S. gas exports, Russia can also indirectly affect the availability and price of U.S. natural gas because so much of it is associated gas—natural gas produced with oil from the same well. Associated gas accounts for almost one-third of total U.S. gas production, so any shut-in of U.S. shale oil wells in response to low oil prices will result in a fall in gas production. Indeed, the fall in oil production by nearly 1 mbpd between January and May 2020 resulted in a decline in associated gas production of around 3 bcf/day. Russia is implicated because it was partly responsible for the steep fall in oil prices in March-April 2020; since then, it has been determined not to let oil prices rise too much beyond $50 per barrel, since higher prices would encourage a shale oil comeback. Meanwhile, less gas production should chip away at the gas glut, which preceded and has been compounded by the pandemic lockdowns, resulting in slightly higher prices (and profits) for U.S. natural gas producers—anticipated to reach nearly $3 per MMBtu in January 2021 compared to about $2 per MMBtu in January 2020.

Notwithstanding the above, it is important not to overestimate Russia’s influence over gas as a component of U.S energy security. Structural changes are undermining Russia’s role in the global gas market. For instance, standard long-term gas contracts used by Gazprom are being replaced by shorter-term ones. According to one estimate, 75 percent of European gas was sold at spot prices in 2018 compared to just over 20 percent in 2005. This offers opportunities for U.S. and other gas exporters whose pricing model offers flexibility and reduced risks for customers, particularly now when gas demand is fluid due to uncertainties about economic recovery from the coronavirus pandemic. Consequently, although U.S. LNG exporters were plagued by cancellations of spot orders from Asia in mid-2020, some of this gas has been snapped up by Turkey.

Moreover, with demand for natural gas projected to grow more strongly than other hydrocarbons, U.S. gas exporters face constraints apart from Russia that impact market diversity outside of North America. Total U.S. LNG exports have increased exponentially from 4.4 bcm to 47.5 bcm between 2016 and 2019—more than double Russia’s 20.5 bcm of LNG in 2019—and are projected to grow steadily if supported by fast-tracked approvals and private investments for new LNG export terminals in the U.S. This latter caveat is significant because LNG is projected to play a larger role in global gas markets, reaching 40 percent in 2040, up from 20 percent in 2018. In this regard, Russia’s belated focus on LNG exports is a rising challenge to U.S. LNG; however, shipment-related issues such as winter conditions, lack of LNG carriers and the risk of U.S. sanctions on foreign-owned carriers transporting Russian gas could impede growth. The ability of the U.S., which was the third largest LNG exporter in 2019, to out-produce and out-export fourth-place Russia in Europe and Asia also depends on LNG leader Qatar—specifically, on its ability to follow through on increasing its gas exports from 77 million to 126 million tons by 2027 and purchasing up to 100 new LNG carriers that will give it more control over the entire gas supply chain. (In South Korea, for instance, Qatar will be just as keen as the U.S. to take advantage of the country’s coal-to-gas switch with the goal of retaining, or better yet augmenting, market share, which currently stands at 28 percent versus the United States’ 13.)

On the global stage, apart from the oft-described gas struggles in Europe, the effectiveness of Russian gas diplomacy in Asia has been mixed. The former Soviet republics of Central Asia, for example, were once obliged to sell all their gas to Russia at low prices due to the absence of alternative export routes, but gas pipelines bypassing Russia have since been built. These pipelines were welcomed by the U.S. in the belief that they strengthened independence from Moscow. Today, only 23.5 percent of the region’s gas goes to/through Russia, while 68.2 percent is destined for China; Russia’s economic influence over Central Asia has correspondingly declined although it retains other forms of leverage over the region. China is another arena of Russian and U.S. gas rivalry. Since 2013, the Chinese government has embarked on a drive to improve notoriously poor levels of air quality; part of this involves increasing the use of cleaner-burning natural gas at the expense of coal in power plants. This would require massive gas imports given constraints in domestic gas development, with one report identifying China as the single largest contributor to global gas demand growth between 2019 and 2025. At first glance, Russia’s massive Power of Siberia gas pipeline to China’s northeast appears to have shut out U.S. LNG exports and an opportunity to improve Sino-U.S. relations. However, the pipeline was never going to be competitive in inland areas of China: In a few years, when the second phase of the Power of Siberia moves southward and toward the coast (where LNG is easily delivered), the length of the pipeline route and the cost of gas will increase and the economics may favor U.S. LNG.

Ultimately, as with oil, ownership structure could constrain the ability of the U.S. to marshal gas exports to contend with Russia on the global stage. While state-owned and state-aligned companies in Russia can be pressured to act as agents of state policy, this is much less possible in the privately owned oil and gas sectors in the U.S. where thousands of independent producers make decisions based on price signals and other economic factors. Since gas is partly yoked to oil—both in terms of price indexation and associated gas production—a sustained period of oil prices under $20/barrel in the aftermath of Covid-19 would reduce production in the U.S. and delay the “dominance” agenda.

Coal

The U.S. and Russia are both major suppliers of coal, occupying fourth and third place, respectively, among the world’s net coal exporters. As of 2019, they possessed the largest and second-largest proven reserves of coal—nearly one quarter of the global total for the U.S., 15 percent for Russia. It isn’t surprising, then, that Russian coal barely figures in the United States’ own energy mix. Moreover, domestic demand for coal in the U.S. has been falling, but that, as noted earlier, has to do with the economics of fuel-switching (namely, cheaper gas). The ongoing retirement of coal-fired power plants in the U.S. and the absence of plans to build new ones suggest that the country’s coal industry will increasingly look to export markets. In this scenario, one would expect Russian and U.S. coal exporters to compete for buyers, but each group is currently facing obstacles that have little to do with the other, such as transportation logistics and tariffs.

With coal rapidly falling out of favor in Europe due to the low-carbon energy agenda, Asia, where demand remains strong, is very much the battleground for coal exporters. Russia is aware of the need to diversify away from Europe, now its key market: Europe accounted for just over one-third of Russia’s coal sales between 2016 and 2018, but the region’s electricity generation from coal in 2018 was 30 percent below 2012 levels. In contrast, in China—which is both the world’s largest coal importer and its largest producer—and in India (the world’s second largest importer) coal accounted for 58 percent and 56 percent, respectively, of the primary energy mix in 2018. Although coal’s dominance in China and India is expected to decline by 2040, it will still be the main fuel in their energy mix. This is due to the availability of coal both domestically and from abroad, its cost effectiveness and the young age of their coal-fired power stations, which can operate for decades to come.

U.S. coal, however, struggles to compete in Asia and is much less significant than other fossil fuels in terms of foreign market penetration and revenue. The U.S. accounted for 1.1 percent of China’s coal imports and 7 percent of India’s in 2018; its best performance in China since 2000 was 4.4 percent in 2013. This is largely due to high shipment costs to Asia compared to nearby coal exporters Australia—by far the largest coal exporter in the world—and Indonesia. Chinese tariffs and duties stemming from the Sino-U.S. trade war have worsened the situation, adding 30.5 percent and 26 percent to the cost of metallurgical and thermal coal, respectively. With India considering a ban on coal imports in 2023 to reduce the country’s overall trade deficit, U.S. coal exports are unlikely to make much headway in the next five years. As for Japan, where the U.S. has a 10-percent market share, prospects for coal exports are tempered by the fact that a plan for 22 new coal-fired power plants was a downward revision from 38 plants proposed in 2018; the country also plans to phase out up to 100 older plants. With a new report that the majority of recent solar and wind projects have resulted in lower electricity costs than new coal-powered plants, it is not inconceivable that Japan’s demand for coal will be scaled down again. While all this is grim news for U.S. coal exporters, they may spell opportunities for U.S. gas exporters, particularly since current low gas prices make gas-fired electricity competitive with coal.

Russia does not significantly impede U.S. attempts to increase coal exports and gain market share, even though it exports twice as much coal. The United States’ difficulties in global coal markets have little to do with Russia’s actions, as noted above. Russia’s own attempts to increase its 8-percent share of China’s total imports is hampered by Beijing’s continued imposition of tariffs on coal imports from Russia—despite the signing of a free-trade agreement between China and the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union; this renders Russian coal less competitive with that from Australia. (Russia could benefit, however, if current tensions between China and Australia over the latter’s insistence on an international investigation into the origins of the coronavirus result in Chinese tariffs on Australian coal.) The Sino-Russian coal trade is also constrained by the underdevelopment of railway and port facilities in new coal mining areas in the Russian Far East. While coal exports are significant for the Russian budget (it is the fifth largest source of revenue), conditions in Europe and China may hamper the achievement of a global export share of 25 percent, up from 15.1 percent in 2019, as envisioned in the country’s Energy Strategy till 2035.

Nuclear

In terms of energy availability, U.S. dependence on Russia is higher for uranium than for any other fuel, but Russian supplies make up a small fraction of the U.S. mix and the risk of supply disruptions or price hikes is well tempered by the United States’ diversity of suppliers. As a competitor for markets, Russia is a powerful player on the global map of nuclear-energy production, but it has barely any impact on the vitality of the U.S. nuclear industry; the latter’s myriad problems stem from global trends, economics and public opinion—not anything Moscow has wrought. Obviously, nuclear energy has much to offer in terms of environmental sustainability, but here, too, Russia plays little if any role in U.S. policies.

On global markets, nuclear energy is a sphere where Russia is clearly dominant vis-à-vis the U.S., particularly when one takes into consideration reactor exports, plant-operation services and fuel exports. Rosatom, Russia’s state-owned nuclear energy behemoth, is the world’s only one-stop shop for all things nuclear. It has the largest portfolio in the world of ongoing construction of reactors in foreign countries, partly thanks to generous financial terms backed by the Russian state, which allow poorer countries to fund construction through low-interest loans. In contrast, storied U.S. nuclear companies like Westinghouse and General Electric have had much less success and much less export support from their government. Potential clients are obliged to sign, prior to cooperation, what is known as a “123 agreement” to abide by U.S. nonproliferation principles; Russia requires no such preconditions.[2] As a result, commercial companies and policy analysts alike have warned that America’s back seat to Russia and China in nuclear energy “threatens American competitiveness and national security” and that “Russia and China use trade in civil nuclear technology to gain influence in regions of strategic value.”

Although the U.S. imports 90 percent of its uranium, while Russia has large uranium reserves and hosts half of the world’s uranium-enrichment capacity, Russia has no significant impact on the reliability of the U.S. nuclear fuel cycle. America’s diversity of uranium suppliers means that Russia’s share (13 percent) of U.S. uranium consumption is balanced out by fuel from close allies Canada and Australia (42 percent combined) and domestic mines (10 percent), as well as other foreign sources. Although the Russian state owns Uranium One, a company with mining rights in the U.S., its impact on uranium availability for U.S. nuclear plants is not unduly worrisome. Uranium One accounted for less than 6 per cent of U.S. domestic production of uranium in 2017, it is not licensed to export the uranium it mines, and any attempt to limit production is easily overcome with imports or stockpiled uranium (see below). Moreover, the fact that more than two-thirds of global nuclear fuel-fabrication capacity is located in the U.S. and in allied countries in Europe and Asia means there is no problem with the availability of fuel assemblies used by reactors in the U.S. In fact, a case can be made that Russia should be concerned about attempts by Westinghouse to produce fuel that can be used in Russian-made reactors in Europe; previously, Rosatom’s subsidiary was the only fuel manufacturer for these reactors.

The atrophy of the U.S. nuclear industry, as noted above, has little to do with Russia. Instead, the sector’s decline—and the associated loss of industrial supply chains and specialized skills—came from: global-level trends, including the falling costs of solar and wind energy; the relative abundance of uranium, which makes mining less profitable; high upfront capital costs and long lead times for nuclear power plants; and public fears over nuclear safety. It is also a result of national-level choices in the U.S. to privilege the use of coal and gas over nuclear energy in power generation. Russia has not played a direct role in contributing to these problems.

As with hydrocarbons, Russia’s primacy on the market for nuclear fuel and technologies has sparked debates about Moscow’s ability to use energy as leverage over U.S. allies and other countries. The depth and duration of nuclear commerce (a nuclear plant has a lifespan of at least 60 years), along with clients’ perceived dependency, have led European analysts to caution that supplier countries can gain geopolitical influence over recipient countries. Some U.S. analysts have likewise argued that Rosatom and its planned or ongoing nuclear-plant projects in Europe and the Middle East—for instance, in Finland, Czech Republic, Egypt and Turkey—are inimical to America’s regional clout. Nevertheless, two recent reports by independent think tanks caution that “evidence of nuclear commerce serving as an effective tool of foreign policy leverage in specific instances is limited in nature and hard to substantiate.” In any case, Rosatom has thus far escaped the sanctions that have befallen its hydrocarbon peers, suggesting that U.S. policymakers are not convinced of the company’s alleged malevolence or its role in Russia’s muscular foreign policy.

At the same time, the current U.S. administration has recently called for the revitalization of the U.S. nuclear industry and U.S. global leadership in the sector, with explicit references to the robust competition from state-owned Russian and Chinese nuclear entities. In December 2019 the nuclear energy industry welcomed a seven-year reauthorization of the U.S. Export Import Bank, which relaxed the rules for providing financing solutions for exports over $10 million. In February the administration asked Congress to approve $150 million in funding per year over 10 years to create a strategic stockpile of domestically mined uranium, again citing competition with Russia and China. The efficacy of a stockpile is questionable, however, given the abundance of uranium and the fact that supplies from “friendly” and domestic sources more than balance out those from Russia and Kazakhstan (which has jealously guarded its sovereignty vis-à-vis Russia since independence). Even small modular reactors, touted by the U.S. Department of Energy and promoted by some as game-changers for the nuclear industry, are highly unlikely to generate cost-effective electricity.

In any event, Russia’s dominance in the nuclear energy sphere may not be sustainable at the same blistering pace for much longer. In addition to the long-term fall in demand for nuclear energy noted above—which led Vietnam, for example, in 2016 to cancel its agreement with Russia to build a nuclear power plant—Russia may have to contend with competing demands on its sovereign wealth fund. Prioritizing funds to cover the budget deficit due to lower hydrocarbon exports or to advance the national projects backed by President Vladimir Putin may leave less upfront financing available for some of Rosatom’s reactor construction projects. China’s nascent reactor export business would be the obvious beneficiary of such constraints and it could eventually become a formidable rival to U.S. developers of small modular reactors, although it would have to overcome some major hurdles.

Cyber Attacks

As noted in the executive summary, one impact Russia could theoretically have on U.S. energy systems’ resilience to disruption involves cyber intrusions. Russia and Russian proxies (along with China) have been named in at least two recent reports as high-intent and high-capability perpetrators of major cyber incidents worldwide; according to one of the reports, based on publicly available information, in 2006-2018 Russian actors were believed to be responsible for 98 such incidents—defined as incurring losses of more than $1 million each—although it is often difficult to determine what role, if any, the state plays in these incursions. In 2015 and 2016, researchers blamed Russian hackers for a series of power outages in Ukraine following Russia’s annexation of Crimea and support of armed conflict in eastern Ukraine. As for the U.S., it took the unprecedented step in 2018 of publicly blaming the Russian government for a series of cyber infiltrations of “energy sector networks” in the U.S.; this built on earlier reports of Russia-linked hacks into electric-grid, gas and nuclear-power facilities. A Department of Homeland Security cyber-security official told reporters at the time that no operational control systems had been breached, but that U.S. officials were wary of Russia’s intent.

With an economy 10 times smaller than the U.S.’s, Russia likely sees cyberattacks of various sorts as a relatively low-cost method of undermining the U.S. and other adversaries, and energy security can be a target. Cyberattacks are also appealing in that they are difficult to attribute definitively, hence providing a modicum of deniability of state involvement. (This logic parallels the use of Russian private military contractors in conflicts such as those in Ukraine and Syria.) Whatever Russia’s role in such attacks, the reliability and availability aspects of U.S. energy security are being affected by the increasing adoption of “smart” grids, peer-to-peer electricity trading, and decentralized power generation systems, including micro-grids. While such decentralization may improve the resilience of the overall national electricity grid, the growing number of access points also gives rise to new opportunities for disruptions, meaning that security measures will need to be improved as well.

A Renewable Future?

This primer has examined Russia’s impact on U.S. energy security and the extent to which it could change over the next five years. It concludes that Russia’s biggest impact comes from oil and gas—specifically, from its export of these resources and its shared governance of global oil production—which, in turn, affect U.S. gasoline prices, economic growth and foreign energy policy. At the other end of the spectrum, Russian nuclear power and coal have minimal impact on U.S. energy security, while Russian threats to the resilience of U.S. energy systems have remained latent thus far. This leaves the question of sustainability.

Over the longer term, increasing the uptake of renewable energy and of electric vehicles could offer the U.S. more robust energy security vis-à-vis Russia and greater environmental sustainability than continuing to rely on fossil fuels and nuclear energy, which produces radioactive waste. Six U.S. states have already enacted laws requiring 100 percent clean electricity by 2050 or earlier and over 100 American cities, containing 15 percent of the U.S. population, are committed to the same goal. Renewable electricity and equipment can be exported and leveraged in tandem with clean-energy diplomacy; in fact, the newly reauthorized U.S. EXIM Bank was given a new mandate to commit at least 5 percent of its annual disbursements to supporting renewable energy exports. Increasing the proportion of U.S. electricity powered by renewable energy resources will also reduce reliance on oil and gas, thus buffering the U.S. from Russia’s impact in these markets. This is especially pertinent since solar and wind energy are not key components of Russia’s energy policy: As of spring 2019, less than 1 percent of Russia’s electricity was generated by solar and wind and progress on future non-hydropower renewable-energy projects is slow, partly due to onerous legislation that mandate 65-70 percent of construction materials for solar and wind must be produced in Russia. The country, however, scores poorly on corruption (it was ranked 137th out of 180 countries in 2019) and Russia is also a relatively minor player in the production of rare earth minerals that go into components for renewable energy technologies including solar panels, wind turbines and batteries: It has a 1 percent share of global production compared to the U.S.’s share of 12 percent. In this regard, some see U.S. leadership in renewable energy as the “ultimate weapon” against Russia.

Nonetheless, renewable energy runs into a similar limitation as oil or gas “dominance”—namely, that it is almost impossible to be self-sufficient throughout the clean-energy supply chain, which encompasses raw materials, processed materials, components, products, technology and a whole ecosystem. For example, in terms of raw materials alone, the U.S. is dependent on foreign imports for 50-100 percent of various inputs required for solar panels, wind turbines and batteries. In the end, true energy security for the U.S. may only be achievable through “shared security” in the context of an interdependent North American energy market alongside strong energy partnerships (hydrocarbon, renewable and nuclear) with traditional allies like Europe and resource-rich Australia, with the latter already a key member of the U.S.-led Free and Open Indo-Pacific initiative.

This report was made possible with support from Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Edited by Natasha Yefimova-Trilling and Simon Saradzhyan.

Footnotes

- “Russian Oil and Gas,” CEEMEA Equity Research, JP Morgan Cazenove, March 30, 2020.

- Oil is traded on its future price, so the WTI price recorded in April was for U.S. oil that was physically delivered in May. Negative pricing is rare but means that U.S. oil producers were paying buyers to take oil off their hands given the perception of a lack of oil-storage capacity, since oil demand was sharply curtailed by Covid-19 related lockdowns.

- As far as the author is aware there have been no instances of these less rigorous rules leading to lapses in nuclear security, in part because Russia is a signatory to all IAEA-mandated agreements signed by nuclear suppliers on nonproliferation.

Li-Chen Sim

Li-Chen Sim is an assistant professor at Khalifa University of Science and Technology in Abu Dhabi.

Image shared under a Pixabay license.

This report was made possible with support from Carnegie Corporation of New York.

Edited by Natasha Yefimova-Trilling and Simon Saradzhyan.

The opinions expressed herein are solely those of the author.