Who ‘Defeated’ ISIS? An Analysis of US and Russian Contributions

With Russian flags now flying over abandoned U.S. military bases in Syria, and American soldiers still dying in combat with the Islamic State in Iraq, the terror group’s strength may seem hard to gauge. Yet the Russian and American presidents have each suggested at different times that ISIS, as the group is also known, has been eliminated and that it was their respective militaries that had contributed the most to achieve that result. President Donald Trump, for example, effectively announced the group’s defeat by U.S. troops on July 16, 2019: “We did a great job with the [ISIS] caliphate. We have 100 percent of the caliphate and we’re rapidly pulling out of Syria,” he said at a Cabinet meeting. President Vladimir Putin has made similar comments about the role of Russia and its soldiers. In early December 2017, a few days after the Defense Ministry officially told him that “all ISIS gangs on Syrian territory have been destroyed and the territory itself has been liberated,” Putin travelled to Syria and addressed Russian troops at the Hmeimim military base, saying that, “in a little more than two years, Russia’s Armed Forces, together with Syria’s army, routed the most battleworthy group of international terrorists [there was].”

These claims of victory raise at least two important questions: First, to what extent has ISIS been defeated and, second, which country, the United States or Russia, deserves credit for contributing the most to this cause? The short answer would be this: The U.S.-led coalition did far more to clear ISIS out of Iraq and Syria than Russia and its allies; however, even though the terror group no longer controls significant territory in these countries, its fighters continue to carry out deadly attacks there, waging what the Institute for the Study of War recently called “a capable insurgency” with “a global finance network,” showing that any purported victory over ISIS—whether claimed by Washington or Moscow—is extremely “fragile.”1

ISIS: Down but Not Out

While there is little doubt that ISIS had by the summer of 2019 lost control over most, if not all, of its territorial “caliphate,” it is also clear that the group has not been fully defeated, strategically or militarily. In the past two years we have seen ISIS once again become an insurgency group engaged in hit-and-run tactics and brutal terrorist attacks not only around the globe but also in areas supposedly liberated by U.S.-led coalition forces in Iraq and Syria. Between the summer of 2018 and late March 2019, ISIS carried out at least 250 attacks in areas outside its control in Syria, according to a New York Times estimate. In Iraq, the numbers seem to be much higher: Research by the Combating Terrorism Center identified 1,271 attacks there by ISIS in the first months of 2018 alone, including a twin suicide bombing in Baghdad that left 38 dead and over 100 wounded. Other notable attacks in Iraq in the past two years have included a bombing at the funeral of anti-ISIS militiamen, which killed 16, a mortar attack on a soccer field near Kirkuk, which killed six, and a minibus bombing last September, which killed 12. This year ISIS fighters have continued the onslaught, killing three Iraqi soldiers with a roadside bomb in April and attacking two Iraqi security posts near the Syrian border in January. Inside Syria itself ISIS’ most prominent recent attacks include: a series of coordinated suicide bombings in the southwestern region of Suwayda in July 2018, which killed over 200 people; a January 2019 suicide attack at a restaurant frequented by U.S. military personnel in Manbij, which killed 19 people, including four Americans; and three near-simultaneous bombings in Hasakah province in July 2019. This February, according to one Syrian NGO cited by The Media Line news website, ISIS and other groups carried out 53 attacks in SDF territory in the country’s northeast, “mostly targeted killings and home invasions” in the regions of Deir ez-Zor and Raqqa.

In addition to staging attacks, the terror group’s fighters and supporters are dispersed across both countries, “reconstituting key capabilities” since late 2018, according to ISW; a recent Pentagon report concurred, saying that ISIS—also known as ISIL and IS—has now “solidified its insurgent capabilities in Iraq” and is also “resurgent in Syria.” ISIS fighters have taken refuge in Iraq’s “most forbidding terrain,”2 where government control is tenuous at best, “including mountains and caves, remote desert, orchards, river groves and islands,” as well as in “destroyed and abandoned villages,” according to a recent report by the International Crisis Group, or ICG.3 (An attempt to clear ISIS militants out of one such area, a cave complex, in Iraq on March 8 led to this year’s first U.S. troop fatalities in the anti-ISIS battle.) Likewise, ISIS fighters are present in Syria: in the open expanses of its central Badiya desert, finding shelter in its “rocky outcroppings and caves” and launching regular attacks against exposed Syrian military positions, but also in Raqqa and Hasakah provinces, where ISIS is believed to have a sophisticated clandestine network and has conducted more “complex and ambitious attacks.”4 According to the Institute for the Study of War,5 as of 2019 ISIS had also established a rural network of support on the outskirts of Idlib province, now the last bastion of anti-regime forces in Syria, which Damascus has been trying to retake for months with Russian support. However, while many ISIS militants fled to the province after March 2019, the terror group’s presence in Idlib has been “low-key,” in the words of one analyst, as Idlib is dominated by other jihadist groups, in particular an anti-ISIS coalition called Hei’at Tahrir al-Sham, or HTS. Some of the rebel groups in Idlib have been supported by Turkey, whose intervention in northeastern Syria, coupled with the U.S.’s partial withdrawal from the area, has only served to further strengthen ISIS’ capabilities in this Middle Eastern region, according to a recent Pentagon report.

Russia Played Second Fiddle to US in ISIS Rollback

The research laid out below leaves little doubt that the United States and its allies in the anti-ISIS coalition—key among them Iraqi troops, Kurdish Peshmerga and the Kurdish-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces, or SDF, as well as Syrian Arab fighters—played a primary role in subduing ISIS, while Russia and its allies played an auxiliary role that contributed only marginally to the terrorist group’s defeat. This follows from three factors: (1) that U.S.-led forces dislodged ISIS from more key strongholds and square miles of territory than did Russia; (2) that, despite a major Russian military deployment to Syria beginning in September 2015, Moscow’s campaigns against ISIS began in earnest only in 2017, when the group had already been severely weakened and was compelled to concentrate its forces on fighting the U.S.-backed SDF advance in eastern Syria; and (3) that, in the words of political analyst Vladimir Frolov, Moscow’s main goal had never been to fight ISIS but “to suppress the armed opposition to [President] Bashar Assad’s regime, which by fall 2015 had lost control over 70 percent of the country’s territory and was on the verge of military defeat.”6 Frolov’s assessment, likewise voiced by numerous U.S. experts, finds some reflection in the Russian Defense Ministry’s own 2017 end-of-year statistics on its Syria campaign, which made no distinction between ISIS facilities/fighters and those of other “terrorists” and “militants.”

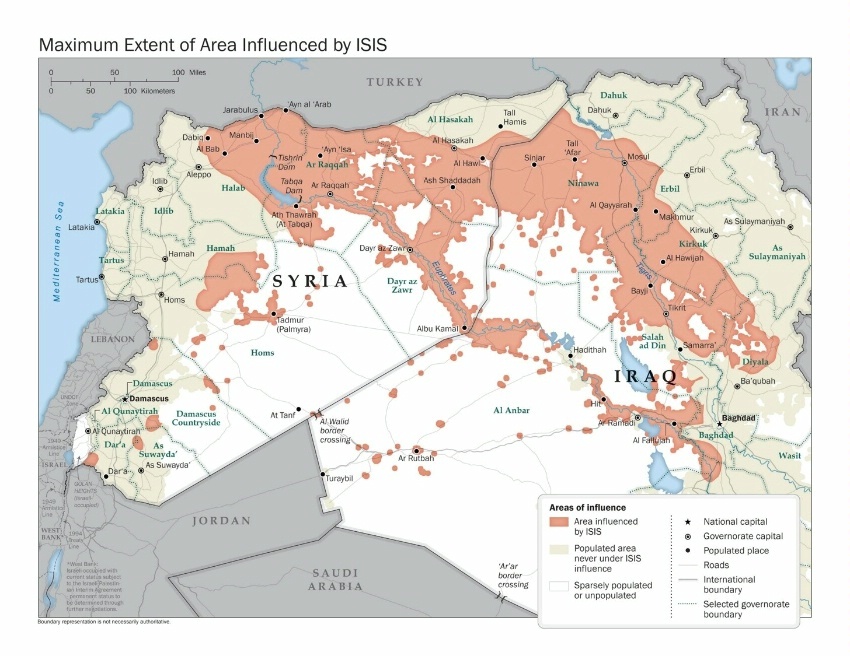

In terms of clearing territory, it is worth remembering that, at its height in late 2014, ISIS had succeeded in taking control of land in Syria and Iraq covering nearly 40,000 sq. miles with a population of 12 million, according to an estimate by the RAND Corporation. The U.S.-led coalition dislodged ISIS from all the areas the group controlled in Iraq, plus a vast triangle of land in eastern and northern Syria—including some of the biggest cities in ISIS’ grip, such as Mosul (where the group’s then leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, declared the creation of the caliphate in June 2014), Fallujah, Ramadi, Tikrit and Raqqa, which eventually became ISIS’ “capital” and main military headquarters. Russia, on the other hand, did not engage militarily against ISIS in Iraq nor did it make other significant contributions to the anti-ISIS effort there, as far as the research for this paper was able to ascertain.7 In Syria, however, it is clear that Russia together with its allies on the ground—the pro-government Syrian forces, Iranian-backed militias and Lebanon’s Hezbollah—wrested at least half a dozen areas from ISIS control in the west and center of the country, contributing, albeit marginally, to ISIS’ defeat.

The United States’ Role: A Timeline

Though Washington did have one costly CIA program supporting anti-Assad rebels in the civil war, by the fall of 2014 the Obama administration had publicly adopted an “ISIL-first” strategy, focusing America’s military might on fighting the terror group. Confronted with the threat posed by ISIS victories in Syria and Iraq—both to the stability of the Middle East and to the well-being of citizens regionally as well as globally—the United States built a broad coalition in 2014 to defeat the terrorist organization. Western partners included traditional allies like the United Kingdom, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark, Italy, Canada and Australia, as well as many other, minor contributors. (Russia did not take part.) Led by the U.S., this coalition engaged primarily in direct airstrikes against ISIS military targets and strategic bases in Iraq and Syria. It also provided training, intelligence and military assistance to allied forces fighting ISIS on the ground. Several forces—funded, trained and equipped by the United States and its allies—did most of the fighting.8 In Iraq, these included the country’s official counterterrorism service (also known as the Golden Division), regular armed forces and police, as well as Kurdish Peshmerga fighters of the Kurdistan regional government, or KRG, which operated primarily in northern Iraq. Several Shia militias supported by Iran also helped the Iraqi government fight ISIS on the ground, but they received neither training nor support from the U.S.-led coalition. In Syria, the U.S. and its allies relied on the Kurdish-dominated Syrian Democratic Forces and U.S.-trained Syrian Arab fighters belonging to the Free Syrian Army. The anti-ISIS coalition also involved other countries in the region, such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Jordan, which primarily provided airpower support to help defeat ISIS but whose efforts were not determinant.

U.S.-led operations against ISIS began in the autumn of 2014 and achieved their first successes in 2015. In January of that year, U.S.-trained Iraqi forces restored control over the Diyala province in the country’s east, while in April the central Iraqi town of Tikrit was returned to government hands through the efforts of a 30,000-strong coalition of Iraqi government troops, Sunni tribal fighters and Shia militias closely advised by Iranian military commanders (including Qassem Soleimani, the powerful general assassinated by the U.S. in January). Again, the United States did not provide airpower to support these operations, as Washington refused to help the Iranian-backed militias fighting in Iraq.

Only in the autumn of 2015 did the U.S. begin significantly increasing the intensity and range of its airstrikes in Iraq, engaging in systematic attacks “against ISIS facilities, command posts, leadership targets and income-generating installations,” according to the Defense Department—an escalation that significantly “weakened” ISIS “and threatened its logistics,” allowing major advances against ISIS on the ground. In mid-October 2015, Iraqi forces and Shia militias reportedly seized the Baiji refinery, Iraq’s largest, from ISIS control in the country’s north. In November 2015, Iraqi Kurdish forces, backed by U.S. air strikes, took control of the northern Iraqi town of Sinjar, one of ISIS’ gateways to Syria where the terrorist organization had perpetrated a massacre against the predominantly Yazidi inhabitants in August 2014. A month later, in December 2015, the Iraqi counterterrorism service together with the Iraqi army made a major advance toward capturing the city of Ramadi, though fighting would last for another month until the city fell. This helped to break the back of ISIS resistance in Iraq’s Anbar province, according to the U.S. military, and opened the way for the capture of Fallujah a few months later. At the same time, in northern Iraq, Kurdish Peshmerga fighters delivered several military blows to ISIS fighters, relieving the pressure “around Erbil and along the disputed KRG border,” according to the International Institute for Strategic Studies.9

The efforts in Syria also started showing signs of success in early 2015, when a coalition of U.S.-backed forces—including Syrian Kurdish fighters from the People’s Protection Units, or YPG, Iraqi Kurdish Peshmerga and Syrian Arab fighters of the Free Syrian Army—began slowly moving south from the Turkish-Syrian border. Their first symbolic victory occurred in January of that year, when YPG forces and FSA fighters restored control over the border town of Kobani after a brutal four-month military campaign that relied on massive U.S. bombing. From Kobani, Syrian Kurdish fighters and their Syrian Arab allies pushed southward and eastward, slowly conquering territory from ISIS with the support of U.S. and coalition airstrikes. In April 2015, they managed to dislodge ISIS fighters from almost all the villages they had captured in the surrounding Kobani province. On June 16, 2015, they took full control of the strategic Syrian town of Tal Abyad, further extending Kurdish control over territory running along the Syrian-Turkish border. A few days later, on June 22, 2015, Kurdish-led forces, aided by U.S.-led airstrikes and smaller Syrian Arab rebel groups, captured a military base near the town of Ain-Issa, some 30 miles north of Raqqa, advancing deeper into ISIS territory.

After the victories of 2015, it took U.S. coalition forces about a year to score a major victory in Iraq. In late June 2016, after a five-week fight, the ISIS stronghold of Fallujah finally fell to Iraqi counterterrorism troops, local police forces and Shia militias supported by a massive campaign of U.S. and coalition airstrikes.10 In August and September 2016, as Iraqi government forces advanced further north, ISIS lost control over what Iraqi officials called its last revenue-generating oil fields in the country, to the south of Mosul and in areas neighboring Kirkuk. In July 2017, after a nine-month fight, the large and symbolically important city of Mosul in northern Iraq was finally recaptured by Iraqi forces and Kurdish Peshmerga fighters, with the support of U.S./coalition airstrikes and U.S. special forces on the ground. The neighboring city of Tal Afar returned to Iraqi hands a month later. In October 2017, Iraqi forces captured the city of Hawija, ISIS’ last stronghold in northern Iraq, leaving ISIS fighters “holed up in pockets of land by the Syrian border.” Finally, in September-November 2017, Iraqi forces launched a successful offensive in Anbar province that allowed them to retake the last patch of Iraqi territory under ISIS control, in the border areas near Syria.11 By the end of 2017, though ISIS fighters were hiding in some remote areas in Iraq, the group controlled no territory there.

The fighting in Syria also progressed in the U.S. coalition’s favor in 2016-2017, with interventions not only by Russia but by Turkey as well. In May 2016, Syrian Kurdish and Arab fighters, now grouped under the umbrella of the SDF, launched a first offensive against Raqqa, intended primarily to test ISIS’ resistance capabilities. Thereafter, SDF forces tried to encircle Raqqa and cut off all lines of communication to the city. In June 2016, the Kurdish-led SDF also spearheaded a successful attack on the ISIS-occupied city of Manbij near the Turkish border, taking control of it in early August. Worried about Kurdish advances, Turkey launched Operation Euphrates Shield on Aug. 24, mostly to prevent Kurdish forces in Manbij from linking up with the Kurdish provinces they held in the northwestern tip of Syria, but also in response to a massive attack by ISIS in Turkey several days earlier.12 Euphrates Shield proved quite successful: Within a few days, Turkish forces and U.S.-backed Syrian rebels dislodged ISIS from the border town of Jarablus and a stretch of land on the Syrian-Turkish border. In December 2016, Turkish troops would liberate the neighboring city of al-Bab from ISIS control, while in November Turkish-backed FSA rebels took control of Dabiq, a town with strong symbolic value for ISIS as the terror group claimed it would be the site of the final apocalyptic battle with Christian forces leading to the ultimate victory of the caliphate.

Also in November 2016, the SDF launched a major offensive to seize Raqqa, approaching it from various directions, with the U.S./coalition providing key air support, including a massive bombing campaign that would last for several months until the city’s fall to Kurdish and Syrian forces in October 2017. In early March 2017, the SDF reached the Euphrates River in northern Deir ez-Zor Province, severing ISIS lines of communication between Raqqa and Deir ez-Zor. A few weeks later, the SDF seized the Tabqah airbase in western Raqqa province, cutting off ISIS lines of contact between Raqqa and Aleppo. In August, SDF forces linked their western and eastern axes of advance in southern Raqqa, and in early September the old city of Raqqa came under their control. Then the SDF units moved further south along the Euphrates and, in September, they consolidated control over most of Deir ez-Zor province, taking over the Conoco gas field, the town of Suwar and the big Jafrah oilfield. The Omar oilfield, the largest in Syria, was seized by the SDF from ISIS on Oct. 22, 2017, two days after the entire city of Raqqa fell to the SDF and U.S.-led coalition, symbolizing the defeat of ISIS’ self-proclaimed caliphate.

By the end of October 2017, therefore, with the support of the U.S. and its allies, ISIS had been cleared from most of the land that it had occupied in Syria to the east of the Euphrates. Only a small patch along Syria’s southeastern border remained under ISIS control, and this area would be cleared by SDF-led forces in March 2019, after a one-and-a-half-month battle to take the village of Baghuz, marking the last nail in the caliphate’s coffin. In sum, ISIS was defeated in a vast triangle of land in eastern Syria—from Kobani in the northwest, to Deir ez-Zor in the southeast, to the borders with Iraq in the east and Turkey in the north. During their entire land campaign, SDF units benefited from massive U.S./coalition airstrikes against ISIS’ command and control positions, its military infrastructure, its leadership and its energy resources, according to the U.S. military.This proved determinant to ensure the SDF’s victory over ISIS; the U.S. and several of its allies also dispatched special-operation forces, which helped to recruit and train SDF fighters and in many instances also took part in military operations on the ground. As Frolov aptly summed it up: “The main role in routing ISIS was played by the U.S.-led international coalition: First, it stopped the ISIS offensive in Iraq in summer 2014 and saved Syrian Kurds from complete annihilation, and then—without direct help from Russia (except aircraft supplies to the Iraqi Air Force)—freed Iraq, including Mosul with its population of several million. In 2017, after thorough preparations, [the coalition] routed ISIS in its capital, Raqqa … and cleared terrorists from the entire eastern bank of the Euphrates, as well as southwestern Syria. While the U.S. was fighting ISIS, Russia was left free to do away with Assad’s main enemies.”13

Perhaps in a testament to the terror group’s resilience, American anti-ISIS efforts have not ceased. As of late March, the U.S. had more than 5,000 troops in Iraq, most of them working “to train and advise Iraqi security forces in the mission against the Islamic State,” according to the New York Times. In Syria, meanwhile, despite Trump’s December 2018 announcement that the U.S. would pull all of its troops out of the country, “an American force of less than 1,000 is arrayed on small, exposed bases across the country’s oil-producing east,” The Washington Post wrote on March 7, in part to keep revenue-generating oil wells out of ISIS hands. (A February news report had put the number of U.S. troops in Syria at 500.)

The Role of Russia: A Timeline

In contrast to U.S.-led anti-ISIS forces, Russia concentrated most of its military efforts on helping the Assad regime regain strength after suffering major losses in Syria’s civil war, which broke out in 2011-2012. Between 2012 and the autumn of 2015, Russia provided military support in the form of equipment, training and advice to help Assad—its longtime ally—fight the insurgency together with Lebanese and Iranian militias. The opposition fighting against Assad consisted of an eclectic mix of groups, some of which were trained and equipped by the United States and its allies, while others included units directly affiliated with al Qaeda, such as Jabhat al Nusra.14 Russia’s military assistance, however, did not prove sufficient to prevent the Assad regime from continuing to lose control over parts of Syrian territory to the Sunni rebels in 2013-2014. By the summer of 2015, the regime seemed on the verge of collapse. This negative predicament prompted Russia to become fully engaged militarily in the conflict. In September 2015, Russian deployed a significant military contingent to Syria, including 12 Su-24 attack aircraft, 12 Su-25 air support aircraft, several Su-30 and Su-35 fighters, as well as at least 12 Mi-24 helicopters, two naval frigates, one cruiser and one destroyer. Soon thereafter, the Russian aircraft began a massive campaign of airstrikes, targeted primarily against opposition fighters who challenged the Assad regime in western Syria. Although the Kremlin claimed that its forces were hitting ISIS targets, most of the Russian airstrikes in the autumn of 2015 were instead carried out against Western-backed rebel groups and jihadist fighters linked to al Qaeda in the provinces of Idlib and Hama. During that period and throughout 2016, Russia focused most of its military efforts on combating opposition fighters entrenched in Aleppo, Idlib, Hama, Homs and southern Damascus—as these were the forces that posed the most direct threat to the Assad regime. This is clearly reflected in the pattern of Russia’s airstrikes, most of which were conducted in these areas rather than against ISIS positions in Syria.

Russian military forces only began fighting the Islamic State in earnest in 2017,15 on the western banks of the Euphrates. The two significant exceptions were, first, the successful efforts carried out by pro-regime forces, with Russian support, to retake the ancient city of Palmyra from ISIS in March 2016 (the city, however, was again lost to ISIS in December 2016) and, second, Russia’s attempts to weaken ISIS positions in the strategic area of Deir ez-Zor where significant oil resources were located. At regular intervals in 2016, Russian aircraft bombed ISIS positions—and occasionally also SDF fighters—in and around the city of Deir ez-Zor, in order to break the siege of the town. Yet it was only once that Assad’s government forces had gained sufficient strength—succeeding in occupying eastern Aleppo in December 2016/January 2017—that they began advancing, with Russian air support, further into Syria’s eastern countryside in order to retake lands occupied by ISIS. By then, the extremist group had been severely weakened. It had been dislodged from most of the lands it had occupied in Iraq through the efforts of U.S.-trained Iraqi forces, Shia militias and Kurdish units, and was also losing ground in Syria. By March 2017, the U.S.-backed SDF had liberated most of northern and northwestern Syria and was starting its offensive against ISIS’ capital, Raqqa. In short, Assad’s advances were facilitated, to a great extent, by the partial withdrawal of ISIS forces from western Syria and their redeployment on the eastern bank of the Euphrates to counter a major U.S.-led SDF offensive. It is not possible, therefore, to argue that Russia played the primary role in defeating ISIS by comparison with the U.S.-led anti-ISIS coalition.

Nevertheless, pro-regime forces, backed by Russian and Syrian air support, did help speed the defeat of ISIS in 2017 by dislodging it from western, southwestern and central Syria west of the Euphrates. On March 2, 2017, pro-regime forces supported by Russian air strikes, Iranian militias and Hezbollah fighters managed to recapture Palmyra from ISIS. A few days later, Assad’s forces and the Iranian and Lebanese militias supporting them seized the Jirah airbase and the Khafsa water treatment plant from ISIS, as well as dozens of towns in eastern Aleppo province, before pushing further eastward toward the banks of the Euphrates. On March 7, 2017, they took control over ISIS-occupied villages near the strategic border town of Manbij (itself liberated by the Kurdish-dominated SDF in August 2016), in order to stop a potential Turkish attack. Also in March 2017, Assad’s forces advanced southward, occupying ISIS-conquered villages and positions in the tri-border region of Daraa, Rif Dimashq and Suwayda provinces in southwestern Syria. All these advances were facilitated by air support from Russian and Syrian armed forces whose planes pounded rural and urban areas. (Russia likewise reportedly agreed to set up a training base for anti-ISIS Kurdish fighters near the northwestern Syrian town of Afrin, presumably to further help Assad counter Turkish incursions by strengthening the Kurdish forces there; however, Turkey would eventually push Kurdish troops out of the Afrin region in a special operation (dubbed “Olive Branch”) in January-March 2018, launched with what one analyst called “Russia’s grudging acquiescence.”)

Between the spring of 2017 and year’s end, pro-Assad forces with significant Russian support from the air managed a number of successes against ISIS: pushing its fighters out of Aleppo province; tightening the regime’s hold on a large swath of territory under rebel control to the west of Raqqa, ISIS’ Syrian capital; breaking the terror group’s three-year siege of Deir ez-Zor city; and taking control of the last remaining foothold of ISIS in Deir ez-Zor province. The rapid advances against ISIS in the last months of 2017 were facilitated by the terrorist group’s decision to deliberately surrender almost all of its territory on the western banks of the Euphrates—Deir ez-Zor, Mayadeen and Abu Kamal on the Syrian-Iraqi border—to pro-Assad forces in October 2017 as its fighters concentrated their defences against the U.S. and the SDF on the river’s eastern bank.16 The milestones in this period, region by region, include the following:

Aleppo Province:

- In mid-May 2017, pro-Assad forces took full control of the al-Jarrah airbase in the eastern Aleppo countryside, aided by heavy Russian and Syrian aerial bombardment. At the same time, Russian and Syrian aircraft intensified their attacks on Maskaneh, in southern Aleppo province, in order to further weaken ISIS in the Aleppo region.

- On June 30, 2017, pro-regime forces took the Ithriya-Rasafa road and cleared the areas to the east of Khanaser from ISIS, forcing its fighters to withdraw from their last territory in Aleppo province.

Raqqa Province:

- In mid-July 2017, Assad’s forces, backed by heavy Russian airstrikes, seized oil wells and several small villages from ISIS in the desert areas southwest of Raqqa. These advances reinforced Assad’s grip on the vast territory stretching from “eastern Hama province to eastern Homs and the edge of Raqqa and Deir ez-Zor provinces,” although areas of central Hama and Homs provinces remained in ISIS and rebel hands for several months afterward.

Deir ez-Zor Region:

- In late July-early August 2017, pro-regime forces and Iranian militias advanced further east toward the city of Deir ez-Zor, on the Euphrates, and by Sept. 6-9 they succeeded in lifting the three-year-long ISIS siege of Deir ez-Zor and its airport. Russia supported these advances with heavy airstrikes and missiles launched from military vessels deployed in the Mediterranean Sea.

- Thereafter, pro-regime forces pushed south along the Euphrates and in mid-September 2017 they launched an operation to clear the Syrian-Iraqi border from ISIS fighters in southern Deir ez-Zor province. This coincided with efforts by Iraqi forces to clear western Anbar province of ISIS on the other side of the border.

- In mid-October 2017, Assad’s government forces and their allies took full control of the town of Mayadeen in Deir ez-Zor province—an area where a large portion of ISIS leadership, media and external attack cells had found refuge after being dislodged from Raqqa and Mosul by the SDF.

- In early November 2017, pro-Assad forces, led by Iranian-backed militias and Hezbollah troops, stormed into Abu Kamal, the last ISIS-controlled city on the border with Iraq along the Euphrates.

Hama and Homs Provinces:

- In the summer of 2017, the Syrian army and Iranian-backed militias also made significant gains in the desert region northeast of Palmyra, capturing the Hail gas field in July.

- On Aug. 7, they took over the town of Sukha in eastern Homs province along the Palmyra-Deir ez-Zor highway. In late August 2017, pro-regime forces, backed by intense Russian airstrikes, seized villages and tightened the encirclement of ISIS positions in eastern Hama.

- In early September, they finished clearing ISIS pockets in northern Homs and eastern Hama provinces, as they captured the town of Uqayribat, as well as 16 villages in eastern Hama, from ISIS. Finally, in early October 2017, the last ISIS pocket in eastern Hama province was cleared.

Southwestern Syria:

- Pro-regime forces also pushed due south from Damascus and, in August 2017, seized a 40-kilometer stretch of land from the Free Syrian Army along the Syrian-Jordanian border in eastern Suwayda province. ISIS fighters were also forced to withdraw from the western Qalamoun Mountains near the Syrian-Lebanese border in the southwestern fringes of the country, as a result of a simultaneous but uncoordinated attack on ISIS positions by Lebanese Hezbollah militias, Syrian army forces and the Lebanese armed forces.

- In October 2017, Assad’s forces gained full control over the town of Qaryatayn, northwest of Damascus in the Qalamoun Mountains, significantly reducing ISIS’ presence in southwestern Syria.

The last of these offensives coincided with efforts by President Putin to find a negotiated political resolution of the conflict—involving the Syrian government, the opposition, Iran and Turkey—and culminated in his Dec. 11, 2017, announcement of the end of Russia’s military operations and the start of the withdrawal of its forces from Syria. Yet ISIS had not been fully defeated then, as now, and therefore Russia not only continued to provide Assad with air power but decided to keep a force of some 5,000 servicemen deployed in Syria17 to help the regime keep fighting what was left of ISIS, but, above all, to defeat the other rebel groups concentrated in Idlib and Aleppo, including those affiliated with al Qaeda. In 2018 Syrian government offensives, supported by Russia and Iran, continued targeting ISIS, as did the U.S.-backed coalition. In May, Assad’s forces launched a massive attack to kick ISIS out of the Palestinian Yarmouk refugee camp on the southern fringes of Damascus, and in July they routed ISIS in areas close to the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights. In July-August 2018, Syrian government forces, supported by an intensive Russian bombing campaign, finally took full control of the Yarmouk basin in southwestern Syria, clearing the region of ISIS. By mid-November 2018, the government had dislodged ISIS fighters from all the southwestern regions of Syria. By year’s end, therefore, the group’s territorial control had been eliminated in most if not all of western and central Syria west of the Euphrates. And although Russia had withdrawn some of its aircraft and helicopters in the summer of 2018, including the new Mi-28 and K-52 attack helicopters, it had left a force of roughly 30 aircraft,18 which continued to provide crucial support to pro-regime forces. Moreover, Russian special forces reportedly supported Assad’s efforts to dislodge jihadist and other rebel forces in several areas of northwestern Syria, including, possibly, in Idlib and Hama in the summer of 2019 (although Russian officials deny this).19 In August 2018, Russia’s defense minister said more than 63,000 Russian servicemen had rotated through Syria in the previous three years; however, Russia’s troop presence there has been estimated at “no more than 4,000-6,000 ground troops … at any given time,” according to the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, and recent estimates have placed the number at “several thousand,” including Russian military police with air support in eastern Syria.

Although Moscow and Washington have managed to keep their separate military campaigns in Syria “deconflicted” for the most part, U.S. officials told the New York Times in February that U.S. troops had been having increasingly frequent run-ins with Russian military personnel on highways in northeastern Syria and that Russian helicopters had been flying closer to American troops. One of the most dramatic collisions between Russian-backed forces and U.S. troops took place near Syrian oil fields in February 2018—some months after both Russia and the U.S. had declared their respective victories against ISIS. In the confrontation, the U.S. military killed an estimated 200-300 pro-Assad fighters, including a significant number of Russian mercenaries, in a firefight that the New York Times called “one of the single bloodiest battles the American military has faced in Syria since deploying to fight the Islamic State”—and certainly one that ratcheted up tensions between Moscow and Washington.

‘Victory’ by the Numbers

The world’s battle with ISIS may be far from over, but insofar as the terror group has been subdued, the United States and its allies, as noted above, played a bigger role than did Russia, and the numbers bear that out. According to the Pentagon, by late March 2019 the U.S.-led coalition had liberated about 42,000 square miles of territory and 7.7 million people from ISIS occupation. In October 2017, when the vast majority of land had been retaken from ISIS, the Pentagon claimed to have killed around 80,000 ISIS militants. Between August 2014 and October 2018, the U.S. and its allies conducted over 30,700 strikes as part of Operation Inherent Resolve and provided military assistance to allies on the ground. Russia, in turn, asserted in December 2017 that it had eliminated 60,318 militants—not specifically identified as ISIS—as well as 8,000 units of military equipment, 718 weapons factories and workshops and about 400 oil production facilities belonging to rebel fighters. A top military commander publicly told Putin at the time that close to 26,000 square miles “of territory [had been] liberated, including over 1,000 populated settlements, 78 oil and gas fields and two phosphate mines”; he also said Russian forces had completed almost 7,000 military airplane raids and over 7,000 sorties by helicopters.

While it is difficult to determine the number of ISIS militants killed or captured by Russia, it is clear that together with its allies on the ground Moscow succeeded in returning to Syrian government hands most if not all of the areas in western and central Syria, to the west of the Euphrates River, that had fallen under ISIS control. These included the al-Hajar al-Aswad district south of Damascus, the besieged Yarmouk refugee camp, rural areas in the central territories of Homs and Hama provinces, as well as a series of villages to the east of Aleppo. Russian-backed coalition forces also twice freed the ancient city of Palmyra from ISIS (albeit, once more for show than substance), as well as Syria’s southern districts in Daraa and Suwayda provinces. By early 2019, with Russian support, Assad’s forces had succeeded in recapturing a vast area of land running from Aleppo in the north, through Homs and Hama provinces in the center, to Damascus and Daraa province in the south, and from Palmyra in the center to Deir ez-Zor and Abu Kamal in the west. In October 2019, The Washington Post estimated that Assad’s regime controlled 57 percent of the country; more recent assessments, made since the U.S. partial pullout, in December and January, placed the Syrian government’s control over territory at 70-73 percent, including major advances into former SDF-controlled areas.

The chief reason Russia’s contribution to the military rollback of ISIS was smaller than the United States’, as described above, is that Moscow’s main goal was to support Assad against rebel groups directly challenging his hold of the country, and those included some groups backed by the U.S. Russia did not start fighting ISIS in earnest until 2017, when the group had already been severely weakened and was sending its remaining forces to the east of the country to face the U.S.-backed SDF advance. Once again Frolov summed it up well, after Russia’s triumphant so-called withdrawal from Syria in December 2017: “Russia began to fight ISIS in earnest only at the final stage of the operation in eastern Syria, during the process of unblocking Deir ez-Zor and accessing the Euphrates. The retaking of Palmyra in 2016 was irrelevant from a military perspective. … It is strange that Moscow is trying to challenge the U.S. and the coalition’s role in routing ISIS. It’s not that the U.S. is trying to ‘capitalize’ on Russia’s victory”—as claimed by the Russian Foreign Ministry’s official spokesperson—“rather, Russia is trying to ‘communize’ the U.S.-led coalition’s victory.”

As noted above, it is too early for anyone to claim victory over ISIS, as the terror group is rebuilding capacity and continuing to launch attacks. Moreover, in addition to ISIS, other jihadist groups continue to operate in the region, posing threats there and beyond. In northwestern Syria alone, these include: the powerful HTS coalition; the Turkish-backed National Liberation Front; the al-Qaeda-affiliated Hurras al-Din; and the Turkistan Islamic Party, or TIP, a jihadist group dominated by Chinese Uighurs.

RM special projects editor Natasha Yefimova-Trilling and RM student associate Daniel Shapiro contributed research for this article.

Footnotes

- See pp. 8-9 of linked ISW report.

- According to the ISW report cited above, these areas include: the Badush and the Makhmour mountains, northwest and southwest of Mosul; the Hamrin Mountains north of Tikrit; the Zagros Mountains in Iraqi Kurdistan; the Jazeera and Anbar deserts; the Zaab Triangle in the north; and the northern Baghdad belts. (See map on p. 19 and details on p. 21.)

- See p. 3 of linked ICG report.

- See p. 23 of linked ICG report.

- See p. 23 of linked ISW report.

- Frolov, Vladimir, “What to make of Putin’s trip to Syria?,” Republic.ru, Dec. 12, 2017, as translated in “The Current Digest of the Russian Press,” Vol.69, No.50, pp. 9-10.

- In October 2015, the Iraqi government reportedly authorized Russia to carry out anti-ISIS strikes on its territory; however, I found no publicly available reports of such strikes. Political analyst Vladimir Frolov mentioned in late 2017 that Russia had sent some “aircraft supplies” to the Iraqi Air Force. See: Frolov, Vladimir, “What to make of Putin’s trip to Syria?,” Republic.ru, Dec. 12, 2017, as translated in “The Current Digest of the Russian Press,” Vol. 69, No. 50, pp. 9-10.

- See, for example: Graham-Harrison, Emma, “Iraq announces ‘victory’ over Islamic State in Mosul,” The Guardian, July 9, 2017; and Karklis, Laris, Aaron Steckelberg and Tim Meko, “The uneasy mix of forces battling the Islamic State,” The Washington Post, Oct. 24, 2016.

- “The Military Balance 2016,” International Institute for Strategic Studies, p. 310.

- See also: IISS’s “The Military Balance 2017,” p. 353.

- See p.19 of linked report.

- On Aug. 20, 2016, a suicide bomber killed 30 people and wounded more than 90 at a wedding in the southern Turkish city of Gaziantep.

- Frolov, Vladimir, “What to make of Putin’s trip to Syria?,” Republic.ru, Dec. 12, 2017, as translated in “The Current Digest of the Russian Press,” Vol.69, No.50, pp. 9-10.

- This group, also known as the Nusra Front, changed its name to Jabhat Fatah al-Sham in July 2016 after declaring that it had severed its formal ties with al Qaeda.

- Again, I found no evidence of Russia operating in Iraq; however, such operations cannot be entirely ruled out.

- See p.23 of linked ISW report.

- “The Military Balance 2019,” Chapter 5, Russia and Eurasia, p.209.

- Ibid., p. 168.

- According to various reports, since the start of the Russian military campaign in Syria, “special” units that have participated in the operations have included special forces of the Main Intelligence Directorate of the General Staff (formerly known as GRU), Special Operations Forces, police and units of Russia’s National Guard.

Domitilla Sagramoso

Domitilla Sagramoso is a lecturer in security and development at the Department of War Studies, King’s College London.

Photo by U.S. Sgt. Lisa Soy shared in the public domain as a U.S. government work.