Why Does Congress Not Care About Normalizing Relations With Russia?

That U.S.-Russian relations are at rock bottom should come as no surprise to anyone even marginally familiar with the list of grievances amassed by the U.S. vis-à-vis Russia in the past few years (and vice versa, though Russia has arguably fewer immediate reasons for falling out with the West). However, even when relations between Washington and post-Soviet Moscow were relatively good, one of the factors that made executive-level attempts at further improvements unsustainable was skepticism, or sometimes outright hostility, on the part of the U.S. Congress. Whether under the Clinton, Bush, Obama or Trump administrations, Capitol Hill has shown a persistent “reticence toward normalizing relations with Russia” and at times “acted as a brake on pursuing any reset” with Moscow, according to eminent Russia expert Angela Stent.1

An obvious question seems to be why—considering that Russia is a rival whose arsenal could annihilate America within hours—do the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives seem to have no stake in normalizing the bilateral relationship? This article attempts to parse some of the major reasons for this. Based on our research, in addition to the aforementioned U.S. grievances (over Russia’s meddling in the 2016 presidential race, intervention in Ukraine and other issues), these reasons include: complacency in Congress about the risk of a “hot” war with Russia despite warnings from experts that this risk has been growing; the tremendous lobbying power on Capitol Hill of the U.S. military-industrial sector, which sees Russia as both a geopolitical adversary and an economic competitor; generally weak U.S.-Russian economic ties that leave too few stakeholders mobilized in support of a better political relationship to have an impact on Congress; lawmakers’ doubts about President Donald Trump’s relationship with Russia, as well as their skepticism toward Moscow dating back to Cold War days; the lack of any meaningful Russia caucus in Congress, while other ethnopolitical lobbies in the U.S. have fought against improved relations with Russia; and the Kremlin’s own seeming struggle to figure out how to engage effectively with lawmakers on Capitol Hill.

As Washington’s relationship with Russia has fallen to what some have called its “lowest point since the end of the Cold War,” Congress has responded both with the rhetoric of threats and actual punitive measures, primarily sanctions, which one senior congressional staffer recently claimed really don’t “cost us anything.” But there is a hidden cost: As stated above, without a normalization of the relationship, the risk of a U.S.-Russian confrontation that could escalate into a nuclear exchange has grown to a level that such respected U.S. statesmen as former Sen. Sam Nunn and former energy secretary Ernest Moniz call the highest since the Cuban Missile Crisis as “arms control has withered, and communication channels have closed.” Congress should also be paying attention to Russia because of its increasing alignment with China. Such prominent U.S. analysts as Stephen Walt have warned that America’s “ineffectual approach to Russia [is] cementing a growing strategic partnership between Moscow and Beijing.” Harvard’s Graham Allison, too, has sounded the alarm about what he sees as a “strategic alliance in the making,” which he considers a threat to the United States. Russia’s ability to share intelligence on international terrorist threats also merits Congress’ attention. In short, members of Congress don’t have to like Russia, but helping to normalize the bilateral relationship would be in America’s interests, according to both Stent and George Beebe, a former director of Russia analysis at the CIA. U.S.-Russia friendship is not feasible at this time, but “predictable competition” is a goal to strive for, Beebe has argued recently. Stent, meanwhile, told us that, “in the best of times, the U.S-Russian relationship is compartmented, with elements of cooperation coexisting with elements of competition. The cooperative element is mostly missing today… Restoring channels of communication would reintroduce elements of predictability into the relationship between the world's two nuclear superpowers.”

Complacency About Risk of a ‘Hot’ War with Russia

During the Cold War era, the specter of impending war with the Soviet Union hung over the United States: Congress allocated tens of millions of dollars for civil defense, including funding for fallout shelters and educational programs teaching schoolchildren how to take part in air raid drills. The government planned for potential nuclear catastrophe, and this risk periodically reminded U.S. and Soviet officials of the indispensability of clear and constant lines of communication—the crux of normal relations. However, between a series of arms control agreements that drastically reduced both countries’ weapons stockpiles and a decade of American hegemony after the Soviet collapse, concerns about imminent nuclear war have faded from the minds of ordinary people and their elected representatives. According to a 2017 national survey, although 39 percent of Americans listed nuclear war as a fear, 20 other issues ranked higher. Among lawmakers, too, concerns about nuclear war diminished following the perceived “end of the great power rivalry between the U.S. and USSR,” according to a former congressional staffer, who also noted that many in Congress see nuclear arms as “crude weapons that do not do as much damage as info and cyber ops.”

Yet levels of concern have been rising of late among analysts, some of whom have called on Congress to implement better safeguards and to fund upgrades to outdated nuclear command-and-control systems. The arms control architecture built up over the past 50 years is slowly crumbling, with some eminent experts on nuclear arms and disarmament, former defense officials, diplomats and scholars warning that the risk of nuclear war—particularly one triggered by miscalculation—is higher now than at any time since the Cuban Missile Crisis or even earlier. The chances of a nuclear weapon being fired in anger are “far greater now than they ever were during the Cold War,” according to Columbia’s Robert Legvold, who has warned that “to doubt the likelihood or significance of a prolonged confrontation would be deeply misguided.” Moniz and Nunn, meanwhile, claim that in recent years “geopolitical tension has undermined ‘strategic stability’” between the U.S. and Russia and that, in this state of instability, an accident “could set off a cataclysm.” They conclude that “Congress must set a tone of bipartisan support for communicating and cooperating with Russia to reduce military risks, especially those involving nuclear weapons. To do otherwise puts Americans at grave risk.” (While not all experts agree on the heightened risks of nuclear confrontation between Washington and Moscow, and though fears of nuclear Armageddon are milder than in the Cold War days, it’s worth noting that the share of Americans who consider Russia’s military a “critical threat” to the U.S. has risen steadily, according to Gallup, from 18 percent in 2004 to 52 percent in 2019; those who consider Russia’s military “not important” has fallen from 29 percent in 2004 to 8 percent in 2019.)

US Military-Industrial Complex Keeps Reminding Congress That Russia Is a Threat

Another factor weighing against Congress-driven improvements in the U.S.-Russia relationship is the formidable lobbying power of the U.S. military-industrial complex, which has worked to emphasize—or, some would argue, inflate—the threat posed by Moscow, spurred on by both geopolitical and commercial competition with Russia. During the 2016 presidential race, for instance, with anti-Russia sentiment running high, U.S. defense contractors repeatedly told investors and shareholders that the “Russian threat is great for business,” according to a report by The Intercept. In May 2016, a representative of the National Defense Industrial Association, a lobbying group, asked Congress to ease the procedure for foreign military sales lest clients start buying “products and services from other nations including adversaries such as … Russia.” In February of that year, the Aerospace Industries Association, a lobbying group representing the interests of some major U.S. defense contractors, accused the Department of Defense of not budgeting enough to “keep America more secure”—in part by responding to “Russian aggression on NATO’s doorstep.” While it is difficult to isolate the cost of the Pentagon’s Russia-related procurements, two possible proxies are funding for the European Deterrence Initiative and for military aid to Ukraine. The former received $6 billion for 2019, with congressional approval, while U.S. security aid to Ukraine between the start of its conflict with Russia and mid-2019 totaled $1.5 billion, according to DoD data cited by the Congressional Research Service. Moreover, aerospace and defense company Northrop Grumman is set to receive as much as $13 billion in research spending through 2025 as part of the Air Force’s replacement program for the Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), a modernization effort that is primarily meant to deter Russia.

The U.S. defense industry’s perception of the “Russia threat” as a source of business is not new, nor is its lobbying around that threat: In the years immediately following the Soviet collapse, lobbyists for the military-industrial complex, anxious about cuts to Cold War-era budgets, fought hard in Washington against President Bill Clinton’s plans to cut defense spending. In the following years, as NATO enlarged, the global board was set for a replay of a Cold War-style cycle of action-reaction: Not only did the military-industrial complexes of both countries revitalize their raisons d’etre but their much needed image of an enemy with bona fide destructive capabilities became something of a self-fulfilling prophecy.

In addition to the geopolitical contests that both countries’ militaries can use to justify increased budgets for R&D and procurement, the last 20 years have seen heightened competition in the arena of global arms sales—and Congress has been active in enhancing the positions of U.S. arms makers at the expense of other countries. Although Russia’s economy and defense budget are miniscule compared with those of the U.S., Russia is second to the U.S. in arms exports worldwide, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, and has penetrated historical U.S. markets, including Latin America and NATO member Turkey. The sole entity responsible for the sale of Russian arms and military equipment abroad, Rosoboronexport (now part of Rostec), was established in 2000 by President Vladimir Putin; it has since sold over $150 billion worth of arms and has a current portfolio of sales for $50 billion. In 2017, the last year for which SIPRI has calculated figures, the total value of U.S. arms exports was $30.6 billion (plus another $100 billion in licensing fees and other agreements), while Russia’s equaled $15 billion.2

What gives the U.S. military-industrial complex particular heft in terms of lobbying lawmakers is both money and job creation. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, the amount spent on defense lobbying has more than doubled since 1998, reaching $126.3 billion in 2018. While not all of these lobbying efforts are aimed against Moscow, the rationale for defense-related budget appropriations presented at congressional hearings often includes identifying Russia as an adversary, as do multiple U.S. strategic documents and threat assessments. In terms of jobs, manufacturing in the sector has been diversified to engage as many congressional districts as possible. Between 2005 and 2011, for example, military shipbuilder Huntington Ingalls Industries ordered parts for its multi-billion-dollar aircraft carriers in 330 of 435 districts, creating jobs in 45 states according to a Navy spokesman. Aerospace behemoth Lockheed Martin provides about 98,000 jobs across the U.S.

Russia Not Important Economically Either to US as Whole or to Most Congress Members

U.S.-Russian trade ties are far from robust, as the figures below will show, and seldom have an impact on crucial concerns for Congress members, such as job creation for their constituents. (One recent exception to the rule, involving aluminum maker Rusal, seems to demonstrate that investments into local economies can be a powerful incentive in stimulating pro-Russian decisions on Capitol Hill.) Moreover, Congress has a long tradition of using economic tools in its attempts to punish Moscow—from the Cold War-era Jackson-Vanik amendment to the Magnitsky Act that replaced it to today’s DASKA and DETER bills. Taken together, these conditions put a damper on relations, as strong economic ties can improve political relationships, according to Stent, a former national intelligence officer who has long taught at Georgetown University. She cites two other bilateral relationships on the global stage as examples—between the U.S. and China, current frictions notwithstanding, and between Russia and Germany. For relations between Washington and Moscow to improve, “we need more deals that create stakes on both sides,” former U.S. ambassador to Russia John Beyrle told Stent in an interview.3 And while there are now major U.S. businesses with a lot riding on Russia, from soft-drink and drug makers to pension funds and oil companies, they do not move the needle on congressional policy toward Moscow: These firms’ Russia-related business rarely impacts the economies of specific U.S. voting districts, and their lobbying efforts for policies favorable to Russia, insofar as they exist, can focus on fine-tipped measures that improve bottom lines without changes to the overall tenor of bilateral ties.

In aggregate, bilateral U.S.-Russian trade is quite low. Russia ranked 28th on the list of U.S. trade partners in 2018, according to the International Monetary Fund. And U.S. exports to Russia in 2017 constituted a mere 0.87 percent of total exports, based on data from MIT’s Observatory of Economic Complexity (compared to Canada’s 12 percent or China’s 11 percent); Russia mattered even less to the U.S. in terms of imports, at 0.71 percent (versus China’s 22 percent and Canada’s 13 percent). Foreign-direct-investment data from the U.S. Department of Commerce paint a similar picture: While U.S. FDI going to Russia and Russian FDI to America in 2017 totaled $14.8 billion and $3.9 billion, respectively, U.S. FDI to China and Chinese FDI to the U.S. amounted to $116.2 billion and $60.2 billion, respectively.

Historically, there is certainly precedent for Congress to display more zeal than the U.S. executive branch in using economic tools as sticks rather than carrots for Moscow—if only because in the view of some Congress members such sanctions either won’t cost the U.S. economy much, due to the weakness of the economic relationship with Russia, or could actually benefit the U.S. side. The 1974 Jackson-Vanik amendment, for example, which tied normal trade relations with the Soviet Union to its policies on Jewish emigration, was not repealed by Congress until 2012—more than two decades after the USSR had collapsed and restrictions on emigration had been lifted—despite repeated efforts in that direction by the Clinton and Bush administrations. Both had hoped to leverage Russia’s free-trade ambitions, including entry into the World Trade Organization, in their diplomacy with Moscow, but congressional resistance stymied this approach. A similar tug-of-war between the legislative and executive branches is playing out now over last year’s bipartisan DASKA bill. The legislation raises the possibility of powerful new sanctions, including potential restrictions on buying Russian OFZ treasury bills, which are hugely popular with foreign investors. In December the State Department stepped in, saying the legislation "risks crippling the global energy, commodities, financial and other markets" and would target "almost the entire range of foreign commercial activities with Russia,” some of which clearly benefit U.S. investors. “The main role Congress could play today in normalizing relations with Russia would be to restore the president's ability to modify or remove sanctions if there is progress on the Minsk negotiations between Russia and Ukraine,” and not to impose new, harsher sanctions, Stent told us this month.

Despite poor relations between Washington and Moscow, some major American firms have kept up billions of dollars’ worth of business in Russia in recent years. Why, one might ask, have they not pushed Congress for better bilateral relations? The answer, it seems, is that, while some of these businesses have pulled out completely since the onset of sanctions, others have been able to keep working in Russia without major changes in U.S. policy—whether because they have not been targeted by sanctions or because they have found ad hoc ways around them. Publicly listed U.S. companies generated more than $90 billion in revenue from Russia as recently as 2017, according to Reuters, with PepsiCo, for instance, reporting that its Russia operations brought $3.2 billion in net revenue in 2017, more than 5 percent of its total. Tobacco giant Philip Morris is reportedly planning new investment projects in the country, as is Illinois-headquartered Abbott Labs. McDonald’s, meanwhile, has switched almost exclusively to local suppliers for its eateries in Russia and continues to see the country as a “High Growth Market.” Boeing—after avoiding Russian sanctions—launched a multi-million-dollar joint venture with its well-connected Russian titanium supplier, VSMPO-Avisma last year. American energy companies with interests in Russia have lobbied quietly against specific sanctions with limited success, but, again, have not pushed for an overall improvement in the U.S.-Russian relationship. Many have managed to hang onto their Russia projects in part or in whole. But after sanctions forced Exxon Mobil to abandon its $3.2 billion joint investment with state-run Rosneft in 2018, a former U.S. energy diplomat suggested that fighting for better bilateral ties was too big a task for energy firms: “It’s a sign that the company realizes that U.S.-Russia relations and in particular sanctions are not likely to change soon… They are an enormous source of friction with the government, and it is better business for them [Exxon Mobil] to steer their business away from sanctioned activities.” Besides, with America’s quick rise as an oil and gas producer, some Congress members are seeing a direct link between punishing Russia and increasing the U.S. share on global energy markets.

For U.S. legislators to oppose sanctions against Russia in the past five years has been rare, but exceptions do exist. While one, as noted above, seems to highlight the centrality to lawmakers of job creation for their constituencies, another is an area where Congress has more or less consistently supported economic ties with Russia—space technology. The first case came up last year, after Mitch McConnell, the Senate majority leader, helped push through a sanctions-relief deal for Rusal, an aluminum giant controlled by sanctioned Russian billionaire Oleg Deripaska. A few months after the U.S. Treasury Department lifted the sanctions against Deripaska—the first such backtracking since 2014—Rusal announced a $200 million investment in a new aluminum mill in McConnell’s home state of Kentucky, sparking allegations of quid pro quo from some of the senator’s opponents. Kentucky’s other senator, Rand Paul, also voted for lifting the sanctions and welcomed the “hundreds of jobs for Kentucky workers” created by the new project. In terms of space cooperation, two prime examples of congressional support have involved Russian-made RD-180 rocket engines—routinely used to launch U.S. military and other government payloads into orbit—and NASA’s cooperation with Roscosmos in sending astronauts to the International Space Station. However, rather than this helping to improve bilateral ties, U.S. officials and commercial firms are eager to shed the dependency and are actively looking for alternatives both to Russian engines and to Soyuz spacecraft, so this aspect of the bilateral relationship is likely to grow weaker rather than stronger.

Election Meddling, Trump and Polarization in Congress Make Normalization Even Harder, as Does Lawmakers’ Cold War-Influenced Skepticism

The circumstances of America’s 2016 presidential election have damaged the prospects for improving U.S.-Russian relations even further, likely for years to come: With U.S. intelligence officials finding that Russian government actors attempted to influence the election in Trump's favor by hacking Democratic political organizations and spreading discord through "disinformation and social media," Russia has become toxic on Capitol Hill. Congress—clearly concerned by Trump’s continued enthusiasm about Putin and largely skeptical of Russian intentions, as during the Cold War—has sought to punish Moscow in ways that the impulsive newcomer president could not easily undo. The 2017 Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act, or CAATSA, for example, turned Obama-era executive orders into a law that greatly limits the president’s power to lift sanctions, and it passed with almost unanimous support—419-3 in the House and 98-2 in the Senate. The harsh DASKA and DETER bills were both introduced by bipartisan pairs of lawmakers. As Jackson-Vanik has demonstrated, legislative sanctions out of Congress can slow down progress toward normalizing relations with another state because they limit “the ability of the executive branch of government to make credible promises that it will relieve sanctions” to reward desired behaviors, political scientist Samuel Charap recently told CNN.

In addition, prospects for America's Russia policy have now been warped by domestic political battles. If Republicans’ wariness of Moscow is rooted in a history of mistrust and hawkishness, many Democrats, including defeated presidential hopeful Hillary Clinton, now see Russia as a threat on the domestic political arena as well—due to its efforts against the party, its open disdain for Clinton and its purported closeness to a Republican president whom Democrats broadly see as incompetent and corrupt. This further hinders efforts at normalization, with rhetoric that seems to increasingly cast Russia as incorrigible. The Senate’s top Democrat, Chuck Schumer, went as far as to call on Trump to “train his fire on the foreign adversary, Russia, that attacked us.” Although Trump’s administration has been relatively tough on Moscow in many respects (whatever the president’s own position on the matter may be), the heightened concerns about Russia among Democratic lawmakers track with public opinion: According to recent findings by the Pew Research Center, three times more Republicans than Democrats have confidence in Putin to “do the right thing.” The latest congressional delegation to visit Russia, in 2018 (the first such visit since before the Ukraine crisis), was made up entirely of Republicans. From a historical perspective, though today’s overlay of domestic political battles onto Russia policy seems particularly caustic, it isn’t entirely new: “As soon as the Republicans won a majority in the U.S. Congress in 1994,” Stent points out in her book,4 “the Clinton administration’s policies toward Russia came under increasing scrutiny, especially from those members of Congress who retained a lasting mistrust of Moscow from the Cold War days.”

To a large degree, it is only natural that Congress views Russia with skepticism: The median age in the House is now 58, and the Senate tends to average a bit older, suggesting that more than half of Congress members grew up in an era when the Soviet Union was America’s No. 1 foe—the “Evil Empire,” a repressive behemoth and existential threat to the country. For government officials to fundamentally change their view of erstwhile enemies, as former Secretary of Defense Ash Carter noted recently, requires a hard-to-achieve act of “mental jujitsu.” And Russia’s own policies haven’t helped—from the Kremlin’s failure to nurture democracy at home and its increasing turn away from the West under Putin to Moscow’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and its election interference in 2016. The latter, in particular, outraged a wide swath of America, adding negative public opinion to Congress members’ disincentives for pursuing closer ties with Moscow: According to Gallup polling, the split in favorable vs. unfavorable opinions of Russia among Americans shifted from 50-44 in 2013 to 24-73 in 2019.

This is not to say that Congress has never attempted to build bridges with Russian counterparts. From the mid-1990s to at least the mid-2000s, a bilateral U.S. Congress-Russian Duma Study Group organized exchanges between the two countries’ parliamentarians, supported in part by private grants. Political analyst Anne-Marie Slaughter has argued that this effort was largely motivated by U.S. legislators’ desire for a greater role in foreign policy and for U.S.-Russian relations to be less “focused on the executive level, a state of affairs that made it necessary to redevelop ties with each change in administration.”

No Real Russia Caucus in Congress, but Other Ex-Eastern-Bloc Groups Have Clout

Nonetheless, Congress has not seen the rise of an effective pro-Russia caucus consistently supporting improved relations with Moscow. The reasons for this are worthy of a separate research paper, but partial explanations include the fractured nature of the Russian-American diaspora and the lack of specific, actionable issues to rally around. Moreover, these weaknesses have sometimes been compounded by strong anti-Russian lobbying from other ex-Socialist-bloc diaspora communities.

The current Congress has upwards of 60 nationality-based caucuses, formally known as Congressional Member Organizations—none of them Russia-specific. Russia-focused CMOs that have existed in the past have been short-lived: In 2011, for example, a bipartisan congressional Russia caucus was created in an effort to increase bilateral cooperation and support Russian accession to the WTO, but it disbanded following the Ukraine crisis after a lengthy period of inactivity. In comparison, other former Soviet republics do have support groups. These include an active Ukraine caucus, whose Democratic participants most recently lobbied for the White House to release a longer transcript of Trump’s phone call with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy, which lay at the heart of this year’s impeachment proceedings in Congress. They also include a Georgia caucus and the Armenian Issues Caucus, which reportedly includes nearly a third of lawmakers in the House and a number of high-ranking senators. The late Zbigniew Brzezinski, a former national security advisor, once referred to the Armenian-American lobby as one of the three “most effectively organized” foreign-ethnic lobbies in the U.S.5 It has excelled at grass-roots mobilization of American Armenians in support of Armenian causes, culminating in congressional recognition of the Armenian genocide last October.

Compounding the absence of pro-Russian voices in Congress, other ethnopolitical lobbies in the U.S. have fought against improved relations with Russia. In the 1990s, for instance, the Polish American Congress worked with representatives of the Polish government to convince U.S. officials to support Poland’s accession to NATO, which Moscow viewed as a direct threat to its security. Even during the Bush administrations of 2001-2009, Stent writes, “ethnic lobbies … who advocated tough policies toward Russia had considerable influence.”6 This included the Ukrainian-American lobby, which, according to Stent, “found a sympathetic ear” among U.S. officials and successfully lobbied the government to pour “money into Ukraine, making it the third largest recipient of U.S. aid after Israel and Egypt.”7 More recently, organizations including the Ukrainian Congress Committee have lobbied for tighter sanctions on Russia and for U.S. shipments of lethal defensive weapons to Ukraine. The co-chairs of the Georgia Caucus, meanwhile, introduced legislation recently to help Tbilisi in its conflict with Moscow, including new sanctions; the bill, known as the Georgia Support Act, passed the House last year before getting stuck in the Senate.

The Russian-American community, while relatively sizeable in terms of population—upwards of 2.6 million in 2017 according to the U.S. Census Bureau8—has not demonstrated such successes in Congress, despite a smattering of groups that have pursued better bilateral ties. The Congress of Russian Americans, for example, opposed CAATSA, but the legislation got resounding approval from lawmakers nonetheless; moreover, the group focuses primarily on culture, education and charity work, not politics, and its resources are miniscule, with 2017 expenditures totaling just over $100,000, according to tax filings. Other groups have focused on narrow business interests, akin to the U.S. firms with stakes in Russia. These include the U.S.-Russia Business Council, the Houston-based U.S.-Russia Chamber of Commerce, which reportedly raised concerns about sanctions with congressional officials in 2018, and the American Chamber of Commerce in Russia, whose representatives reportedly met with Treasury officials last year, advocating for more business partnerships and fewer sanctions.

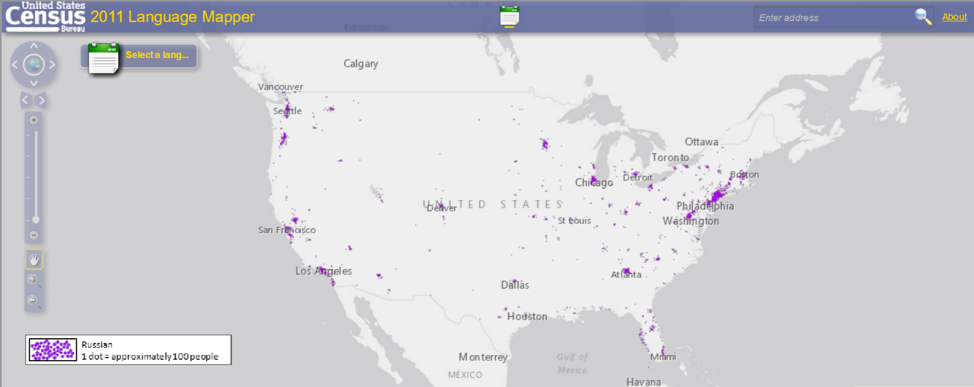

One potential reason for such anemic mobilization efforts is that Russian-Americans, whose arrival in the U.S. came in distinct waves over the course of a hundred years, are a tremendously varied bunch, including a sizeable contingent with no love for the Russian state, according to the aforementioned former congressional staffer, who worked previously with the Russian-speaking diaspora: “Not all Russian citizens living legally in the U.S., or former Russian citizens and even former Soviet citizens, … want to engage with or act on behalf of Russia.” Many recent immigrants wish to work and live in the United States “without rocking the political boat,” while many others “who came to the U.S. much earlier” or emigrated from the Soviet Union now see themselves as “more aligned with the United States,” said the former staffer, who requested anonymity because they currently work in a different field. Moreover, nowadays, plenty of Russian speakers in America—who are scattered widely across the country (see map below)—have a “transitory” relationship with the U.S. and politics are either not attractive or not relevant to them: “Many are Russian citizens who just want to work; some just invested in Miami or New York City real estate and just want to hang out here for a few weeks out of the year; and others simply don’t care.” The former congressional staffer claimed that Russian government attempts to engage compatriots in the United States—especially robust before 2014—had met with lukewarm enthusiasm.

Moscow Struggles to Understand How to Engage With Congress

Another possible explanation for Moscow’s inability to mobilize an effective lobbying presence in Washington hinges on the stark differences between the two countries’ political systems: “Russian officials understand that Congress has been an impediment to moving the relationship forward but have difficulty comprehending the complex relationship between the executive and legislative branches of the U.S. government, perhaps because there is no real separation of power in Russia. The Russian government has also been singularly ineffective in making its case to Congress,” writes Stent.9 Russian political analyst Andrey Sushentsov has offered a similar assessment in harsher terms: “The Russian elite finds it hard to believe that U.S. policy is competitive, that its outcome is not preset, that a real foreign policy discussion is taking place, and that polemics in society, the press and Congress are not a well-orchestrated performance.”

This lack of understanding seems to be exacerbated by Putin’s own preferences in negotiations: The Russian president shows a strong preference for dealing with “the man in charge” rather than engaging in a long-term, multi-stakeholder game full of uncertainties—such as those related to the turnover, as well as the interests, of lawmakers in Congress. This pattern of behavior was evident as far back as 2002-2003 during negotiations between Moscow and Exxon Mobil over the U.S. company’s stakes in various Russian projects and as recently as Putin’s quixotic 2017 attempt to offer Trump a new reset of bilateral relations. Ultimately, as Stent has argued, “in the absence of broad-based institutional ties … and given the limited number of stakeholders in the bilateral relationship, ties between the two presidents have played a disproportionate role … over the past two decades.”

The Kremlin has certainly attempted to invest in policy forums, media projects and PR events—as well as, possibly, some more covert modes of influence—but these haven’t broadly succeeded as lobbying vehicles. It is difficult to put a price tag on those efforts, but it is interesting to note that, according to calculations by the Center for Responsive Politics, almost 99 percent of the $36.2 million in spending reported in 2018 on behalf of Russian entities under the Foreign Agents Registration Act seem to have been spent on media activities by Russian state-run companies rather than classic lobbying meant to directly influence lawmakers. The previous year’s spending was miniscule by comparison—a mere $1.3 million, about two-thirds of which came from two Russian business groupings (Deripaska and Rusal and the VTB banking group) rather than the state per se.

Avoiding Conflict Requires Talking to Adversaries, Armed With Carrots as Well as Sticks

With all the differences between the U.S. and Russia, both in substance and in perceptions, in worldview and in interests, neither Congress nor anyone else can be expected to usher in genuinely friendly bilateral ties anytime soon. Normalization, however, is a lighter lift. At a tactical level, Stent has recommended that Congress give the executive branch greater flexibility in tweaking or lifting sanctions, so that the administration has greater leverage in talks with Moscow. Longer-term, Stent and Beebe both argue for increasing predictability, in part at least by improving communication. Some U.S. officials will likely parry that this is easier said than done. Nonetheless, it is an axiomatic paradox in the field of negotiations that the stronger the differences between sides, the more important it is to have trustworthy communication channels to avoid escalation. The main danger, in Beebe’s words, is that “the United States and Russia are fighting an undeclared virtual war” with no “rules of the game,” no clear distinctions between overt and covert conflict. In this situation, “small events can cause ripples … that produce large, catastrophic outcomes.”

RM founding director Simon Saradzhyan formulated the research questions for this article; he co-edited it with RM special projects editor Natasha Yefimova-Trilling, who also contributed research along with RM student associate Thomas Schaffner.

Footnotes

- Stent, Angela, “The Limits of Partnership: U.S.-Russian Relations in the Twenty-First Century,” Princeton University Press, 2014, pp. 27 and 86-87. (All further references to the book are to this edition.)

- According to SIPRI, each country has its own methodology for counting, so these numbers may not be directly comparable. It is not clear, for example, if the Russian number includes licensing, which the Americans count separately.

- Stent, “The Limits of Partnership,” p. 262.

- Ibid., p. 26.

- “Most foreign governments also employ American lobbyists to advance their case, especially in Congress, in addition to approximately one thousand special foreign interest groups registered as active in America's capital. American ethnic communities also strive to influence U.S. foreign policy, with the Jewish, Greek, and Armenian lobbies standing out as the most effectively organized.” Brzezinski, Zbignew, “The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives,” Perseus Books, 1997, p. 28.

- Stent, “The Limits of Partnership,” p. 102.

- Ibid., p. 111.

- To find the data: Click on “Guided Search” and then on “Get Me Started”; check "I'm looking for information about people" and click “Next”; click the "Origins" dropdown, then “Ancestry”; then click “Next,” and “Next” again through "select a geographic type" without choosing anything; click "Select From Detailed Groups”; in the search bar labeled "Search for a race, ancestry or tribe" write "Russian," select "Russian (148-151)" from the dropdown and click “Go”; click "Russian (148-151)" in the table below; click “Next” and then “Selected Population Profile in the United States” at the top of the resulting table.

- Stent, “The Limits of Partnership,” pp. 260-261.

Daniel Shapiro

Daniel Shapiro is a graduate student at Harvard University specializing in contemporary Russian politics, Russian public/private sector relations and the North and South Caucasus. He is also a graduate student associate with Russia Matters.

Arthur Martirosyan

Arthur Martirosyan, a senior consultant with CMPartners, is a negotiation specialist with more than 25 years of experience in designing and implementing strategic dialogue processes in ethnopolitical conflicts in Eurasia, the Middle East, the Balkans and Africa.

Photo by Council.gov.ru.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the authors.