Yes, Russian Generals Are Preparing for War. That Doesn’t Necessarily Mean the Kremlin Wants to Start One

Russia’s annual strategic military exercises are set to begin Sept. 14, but speculation has been mounting for months that the week-long Zapad-2017 war games in Russia and Belarus might be a prelude to some sort of invasion. A New York Times headline noted that the drills near NATO’s borders “Raise Fears of Aggression,” while CNN wondered: “Could they turn into war?” And Ukraine’s defense minister was quoted as saying that this year’s Zapad could be used to attack any “country of Europe that shares a border with Russia.” The trepidation, especially in Kiev, is understandable: Russia’s three most recent foreign military interventions have indeed been preceded by some deployments masked as military exercises; however, all those operations suggest that at least two conditions must be in place for Moscow to deploy troops and neither of them exists today. Moreover, though the Russian military is certainly preparing for war, that is what generals in all countries do: It’s their job to prepare for worst-case scenarios, and large-scale exercises are meant to test the military’s readiness for them. That doesn’t mean Russia’s military-political leadership necessarily wants this scenario to materialize. But they probably do want Zapad-2017 to deter potential adversaries and warn “disloyal” neighbors against “escaping” to the West.

A Different Ball Game

If Russia’s military interventions abroad over the past decade are any clue, then the main condition for Moscow to seriously consider initiating large-scale use of force against other states—under the guise of military exercises or otherwise—is a belief on the part of the Russian leadership that there is a credible, acute, serious threat, or threats, to one of the country’s vital national interests or its ruling elite. Such threats could include: an attack on Russia or an ally or client, as was the case in the 2008 war with Georgia; the attempted ouster of a friendly ruling regime, as with the ongoing campaign in Syria; or concern that one of Moscow’s post-Soviet neighbors may “escape” to what Russia sees as a hostile alliance, as illustrated in the 2014 conflict with Ukraine, as well as the war with Georgia. (See Table 1 below for a full list of Russia’s vital interests, infringement upon which can cause Russia to use force against another state in the author’s view.)

The second condition is that the overall situation in question has to be conducive to the use of force. In other words, Russian leaders must be sure they would prevail in a confrontation with the state(s) against which they want to use force, or at least ensure a stalemate that would constrain the targeted state’s ability to maintain activities Russia sees as seriously undermining its vital interests.

Neither condition is present at the moment. No new acute, grave threat to Russia’s vital interests or its ruling elite has arisen since last year’s massive Caucasus-2016 exercise, which, incidentally, was also preceded by claims that Russia was going to launch a “full-scale invasion” of a neighboring state or even a “mega war.” Neither Ukraine nor Georgia is anywhere closer to entering NATO. No Russian allies or clients are under greater threat than they were last year. Moreover, some of these clients, such as Bashar al-Assad of Syria, have actually seen threats to their rule diminish in the past year. Nor are prospects for military adventures particularly rosy. Russia’s neighbors are not in a state of acute instability that would hinder their ability to respond to aggression, as was the case with post-revolutionary Ukraine in the spring of 2014. Also, unlike the situation three years ago, when Western nations were caught unaware as Russia used military exercises to conceal its deployment of forces to Crimea, NATO is now keeping a much closer eye on the Russian military maneuvers, especially since some earlier Zapad exercises featured simulations of a first nuclear strike against the alliance. NATO has also beefed up its military presence in its Baltic and Eastern European member states, further reducing the already slim chances that Russia would want to repeat a Crimea 2014 scenario there. Domestically, with Russia already involved in Syria and Ukraine, its citizens hardly want another military entanglement in the absence of a clear threat to them or Russian-speaking minorities abroad. A July 2017 poll by Russia’s state-owned VTsIOM pollster showed that more Russians (35%) support their country’s non-interference in the conflict between Kiev and Russian-backed separatists in Donbass than any other policy option toward that conflict.

There has been some speculation—fanned by former Georgian leader Mikheil Saakashvili—that Russia plans to annex Belarus itself, but this seems unlikely. For starters, while Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko likes to occasionally play Russia and the EU off each other, he differs from the victorious organizers of the “color revolutions” in Georgia and Ukraine in that he shows no intention of steering his country toward NATO. Furthermore, any attempt to take control of Belarus would seriously undermine Russia’s efforts to keep other post-Soviet republics in its various international integration projects. If Russia were to seize Belarus, with which it’s had a “Union State” since 2000, that would signal to other post-Soviet republics—including Kazakhstan, which participates in the Moscow-led Collective Security Treaty Organization and Eurasian Economic Union—that even membership in Russian-led coalitions won’t preclude losses of territory or independence to Moscow. These republics would then probably look for guarantors other than Russia, forcing Moscow to expend resources on dealing with the consequences. The Zapad-2017 war games are officially called a joint strategic exercise of the armed forces of the Russian Federation and the Republic of Belarus. It is difficult to see how Russia could annex Belarus unless it sends much more than the 3,000 soldiers officially scheduled to be in the country according to the Belarussian Defense Ministry.

Practice Makes Perfect

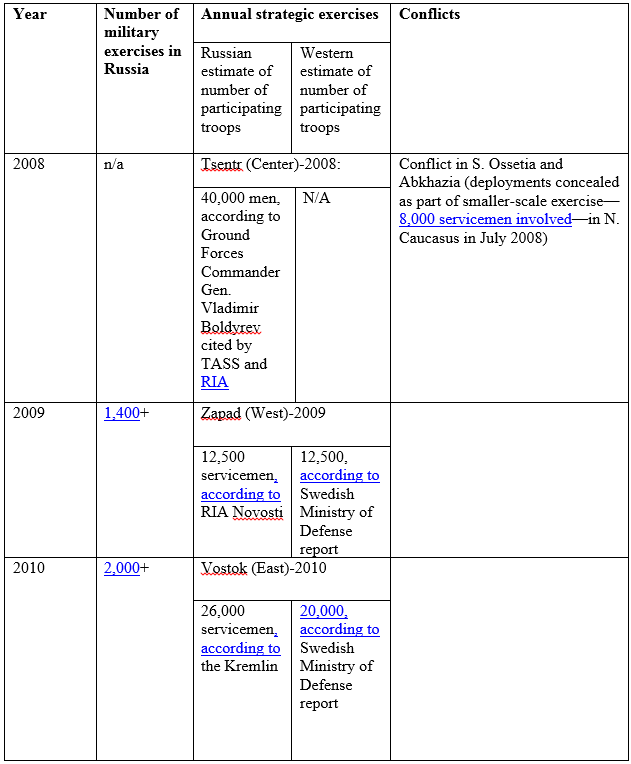

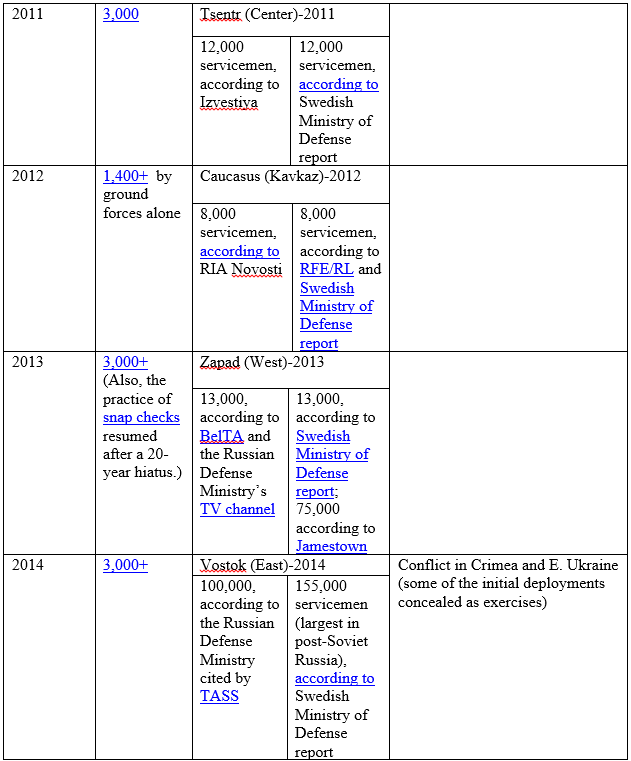

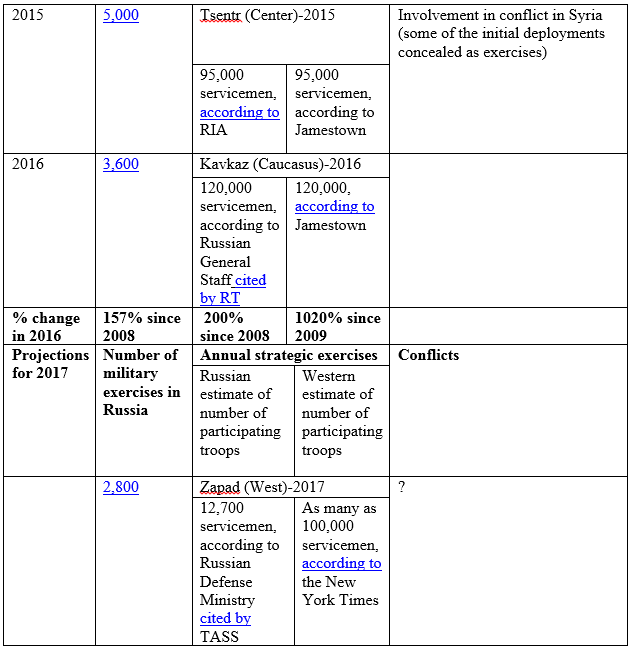

Russian generals love to train, and they are not alone. As one of my Harvard Kennedy School classmates observed half-jokingly back in 2002, U.S. generals dislike wars because they distract their troops from training for them. Russian generals probably hold a similar view. Indeed, the Russian military has been holding large-scale strategic exercises every year of the 21st century, as the Russian economy has rebounded from the lows of the early 1990s. These annual drills take place in four different regions, on a rotating basis, with their names reflecting that: Zapad (“west,” last held in 2013), Vostok (“east,” 2014), Tsentr (“center,” 2015), Kavkaz (“Caucasus,” 2016) and now Zapad-2017. If anything, this rotation of locations among Russia’s strategic operational commands shows that Russian strategists believe their armed forces need to be prepared for a major conflict from any direction, be it with NATO or China. But again, preparing for such a conflict does not mean the Kremlin is planning to initiate one, certainly not without the presence of the two conditions described above.

It’s also worth noting a correlation between Russia’s overall economy and its military spending and training, which suggests that the Russian armed forces tend to train as much as they can afford to. Until 2015, Russia’s military expenditures and the number of war games it conducted—both large- and small-scale—had been increasing at a faster pace than the rate of economic growth. While Russia’s GDP grew by 88% (measured in constant dollars) from 1999 to 2014, its military expenditures grew by 300% in the same period and the number of war games increased by 157% from 2008 to 2014 (see Tables 2, 4 and 5 below). The Russian economy then shrank 3% in 2014-2016, while Russia’s military expenditures shrank by 24% over the same period. As for war games, their number continued to grow in 2015—out of inertia, perhaps—before declining in 2016. Given the fact that the Russian economy has begun to rebound again in 2017, it is likely that the Russian Defense Ministry will continue to conduct thousands of various war games—along with snap checks of combat readiness, which were reintroduced in 2013—for as long as it can afford them.

The official scenario of Zapad-2017, first reported by a Belarusian online publication run by retired officers and later confirmed by Russia’s Deputy Defense Minister Alexander Fomin, is one in which a “Western Coalition” of imaginary states—Lubenia, Wesbaria and Weishnoria (roughly matching on the map, respectively, northeastern Poland, Lithuania and part of Belarus with a relatively high concentration of ethnic Poles)—enter into a conflict with a “Northern Coalition” of Russia and Belarus in order to drive a wedge between Moscow and Minsk, change the regime in Minsk and annex parts of Belarus to Weishnoria. The first phase of the exercise would last for three days, during which the Northern Coalition would focus on isolating areas in which “illegal armed formations” and “saboteur groups” of the Western Coalition have infiltrated Belarus, as well as on ensuring air defense of key government and military facilities. The emphasis on fighting guerilla groups indicates that the planners of Zapad-2017 want to prepare the Russian and Belarusian armed forces for foiling a covert operation resembling what Russian forces themselves pulled off in Crimea in 2014. The plan for the second phase of the exercise, set to end on Sept. 20, calls for Russian and Belarusian forces to hone “command and control in repelling the aggression against the Union State (of Russia and Belarus), as well as the organization of cooperation and comprehensive support.” The exercises will take place in Belarus and the Russian regions of Kaliningrad, Leningrad and Pskov.

The Trust Problem

One aspect of the upcoming Zapad exercises that has been getting a good deal of attention is their size. While some analysts have speculated the drills may be “the largest … in post-Soviet history,” even the highest estimates would make them smaller than Caucasus-2016 and Vostok-2014 (see Table 3 below). Nonetheless, there is a large gap between official numbers and Western assessments. According to Belarusian Defense Minister Andrei Ravkov, a mere 12,700 servicemen will take part; some Western estimates, however, place the number as high as 100,000. This discrepancy—not the first one concerning Russian military exercises, but perhaps the largest—might reflect differences in the ways Russian planners and Western analysts count personnel. While Russian planners only count military servicemen, Western estimates include personnel from other agencies (possibly including border guards and troops from the ministries of interior and emergency situations), according to Dmitry Gorenburg, a senior research scientist in the Strategic Studies division of CNA.

Those skeptical of Russia’s intentions will point out that Russian planners may be underreporting numbers because the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe’s so-called Vienna Document requires OSCE countries to allow in observers for certain military activities involving 13,000 troops or more. In fact, NATO will be sending three observers to Belarus, but just a few, and the alliance has already complained about a lack of access and transparency, saying the observers will be treated like “distinguished visitors” instead of full-fledged inspectors, who would get briefings, interviews with soldiers and overflights. In all, observers have been invited from five NATO countries, as well as from Ukraine and Sweden. Frankly, this also makes me doubt that Russia is planning an under-the-radar attack: Observers can, of course, be kept out of areas of covert deployments, but still it would take an exceptional degree of arrogance to turn an exercise to which you have invited diplomats into an act of aggression or annexation.

There is, of course, always room for greater transparency, and Russia’s neighbors and the international community as a whole would feel more reassured if Russia and Belarus were to provide more details on all upcoming exercises, including snap checks, and grant observers adequate access in compliance with the Vienna Document. The latter could also be modified to lower the personnel quota for exercises that can be held without observers, as well as to require such observers to be invited to snap exercises. Another step in the right direction would be reviving arms control and verification in Europe with Russia’s participation, and under the aegis of the OSCE. However, while helpful, greater transparency and arms control will not qualitatively diminish the chance of a conflict. That possibility will continue to loom large as long as the underlying causes of potential conflict are not addressed, such as Russia’s concerns about NATO’s expansion to the post-Soviet space and Western allies’ concerns about Russia’s use of force against neighbors.

Supplementary Tables

Table 1: Vital interests

|

Russia’s vital national interests that, if threatened, would prompt the Russian leadership to consider use of force (work in progress): |

|

|

|

|

|

Russian ruling elite’s vital interest: |

|

- Moscow has also cited major violations of the basic rights of Russian-speaking minorities as a reason for military intervention, although so far this has been more of a pretext than a genuine cause, as Crimea has shown.

- Full list of Russia’s vital interests can be accessed here.

Table 2: Summary of changes in Russian GDP, defense budget and military training

The Russian military has rebounded at rates higher than the economy that finances it, but there has been a downward trend since 2014.

|

% change in Russian GDP in 2016 compared to 1999 |

% change in Russian military expenditures in 2016 compared to 1999 |

% change in number of Russian military exercises in 2016 compared to 2008 |

|

88% |

204% |

157% |

Table 3: Russian war games

Hyperlinks available in .doc file below. Last modified Sept. 8, 2017.

Note the time lag between change in GDP and change in intensity of military activities.

Table 4: Performance of Russian economy

|

GDP, PPP in constant (2011) US$, billions, rounded (Source: World Bank) |

||||||||

|

Year |

RF |

USA |

GBR |

FRA |

DEU |

ITA |

CHN |

WLD |

|

Year 1999 |

1873 |

12465 |

1871 |

2046 |

2936 |

2006 |

4307 |

60310 |

|

Year 2000 |

2060 |

12976 |

1941 |

2126 |

3022 |

2080 |

4673 |

63174 |

|

Year 2001 |

2165 |

13102 |

1994 |

2167 |

3074 |

2117 |

5062 |

64682 |

|

Year 2002 |

2267 |

13336 |

2042 |

2191 |

3074 |

2123 |

5525 |

66442 |

|

Year 2003 |

2433 |

13711 |

2113 |

2209 |

3052 |

2126 |

6079 |

68953 |

|

Year 2004 |

2607 |

14230 |

2166 |

2271 |

3088 |

2159 |

6694 |

72678 |

|

Year 2005 |

2774 |

14706 |

2230 |

2307 |

3109 |

2180 |

7457 |

76135 |

|

Year 2006 |

3000 |

15098 |

2286 |

2362 |

3224 |

2224 |

8405 |

80217 |

|

Year 2007 |

3256 |

15366 |

2345 |

2418 |

3330 |

2256 |

9601 |

84593 |

|

Year 2008 |

3427 |

15321 |

2330 |

2423 |

3366 |

2233 |

10528 |

87019 |

|

Year 2009 |

3159 |

14896 |

2229 |

2351 |

3177 |

2110 |

11518 |

86696 |

|

Year 2010 |

3301 |

15273 |

2272 |

2398 |

3306 |

2146 |

12743 |

91277 |

|

Year 2011 |

3442 |

15518 |

2306 |

2448 |

3427 |

2158 |

13958 |

94973 |

|

Year 2012 |

3563 |

15863 |

2336 |

2452 |

3444 |

2097 |

15055 |

98040 |

|

Year 2013 |

3608 |

16129 |

2381 |

2466 |

3461 |

2061 |

16222 |

101348 |

|

Year 2014 |

3635 |

16511 |

2454 |

2490 |

3516 |

2064 |

17406 |

104934 |

|

Year 2015 |

3532 |

16940 |

2508 |

2516 |

3577 |

2080 |

18607 |

108407 |

|

Year 2016 |

3524 |

17214 |

2553 |

2546 |

3643 |

2098 |

19854 |

111804 |

|

% change in 2016 compared to 1999 |

88% |

38% |

36% |

24% |

24% |

5% |

361% |

85% |

Table 5: Russia’s military expenditures

|

Military expenditures in constant (2014) US$, billions, rounded (Source: SIPRI) |

||||||||

|

Year |

RF |

USA |

GBR |

FRA |

DEU |

ITA |

CHN |

WLD |

|

1999 |

23 |

379 |

47 |

62 |

51 |

40 |

34 |

1077 |

|

2000 |

31 |

394 |

48 |

62 |

51 |

43 |

37 |

1115 |

|

2001 |

34 |

397 |

50 |

62 |

50 |

42 |

45 |

1140 |

|

2002 |

37 |

446 |

53 |

63 |

50 |

44 |

53 |

1211 |

|

2003 |

39 |

508 |

57 |

65 |

49 |

44 |

57 |

1285 |

|

2004 |

41 |

553 |

58 |

66 |

48 |

44 |

64 |

1359 |

|

2005 |

46 |

580 |

58 |

65 |

47 |

42 |

71 |

1416 |

|

2006 |

51 |

589 |

59 |

65 |

46 |

41 |

84 |

1464 |

|

2007 |

56 |

604 |

60 |

66 |

46 |

40 |

97 |

1522 |

|

2008 |

61 |

649 |

63 |

65 |

47 |

41 |

107 |

1604 |

|

2009 |

65 |

701 |

64 |

69 |

49 |

40 |

129 |

1712 |

|

2010 |

66 |

720 |

63 |

66 |

50 |

39 |

136 |

1738 |

|

2011 |

70 |

711 |

60 |

65 |

48 |

38 |

147 |

1744 |

|

2012 |

81 |

671 |

58 |

64 |

49 |

35 |

161 |

1740 |

|

2013 |

85 |

618 |

55 |

64 |

48 |

34 |

174 |

1719 |

|

2014 |

92 |

578 |

55 |

63 |

47 |

31 |

191 |

1711 |

|

2015 |

91 |

595 |

60 |

61 |

47 |

28 |

214 |

1760 |

|

2016 |

70 |

606 |

54 |

56 |

41 |

28 |

226 |

1682 |

|

% change in 2016 compared to 1999

|

204% |

60% |

15% |

-10% |

-20% |

-30% |

565% |

56% |

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.