In the Thick of It

A blog on the U.S.-Russia relationship

Key to Putin’s Passport Offers to Ukrainians? Russia’s Shrinking Labor Force

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s recent decree to make it easier for residents of some separatist-controlled parts of Ukraine to get Russian citizenship has drawn criticism not only from Kiev but from key partners of the Ukrainian government, such as the U.S., EU and individual EU states. His subsequent statement that this liberalization may be extended to all citizens of Ukraine drew even greater fire, with both the Ukrainian government and its partners accusing the Russian leadership of seeking to assault Ukraine’s territorial integrity, test its newly elected leader Volodymyr Zelenskiy and even engage in banal trolling. The first two of these accusations are not groundless, but they ignore what I think could be the most important among the many factors that have shaped Putin’s decision: Russia needs more working hands and the best way to get them, in the Russian leader’s view, short of an instant demographic miracle, would be to stimulate labor migration from countries where workers are (a) skilled, (b) speak Russian and (c) are culturally close enough that Russian authorities and companies do not have to spend undue money and time trying to train or integrate them. Ukrainians fit these requirements perfectly. Seventy-two percent of its workers had post-secondary education as of 2017 compared to Russia’s 66.6 percent,1 according to the World Bank; most of them are Orthodox Christian and many of them speak fluent Russian.

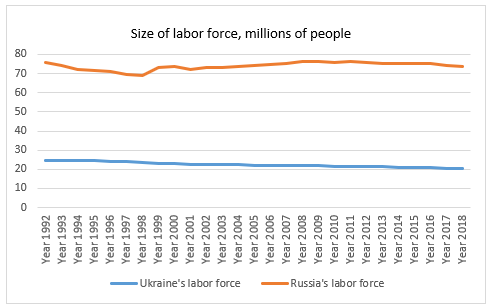

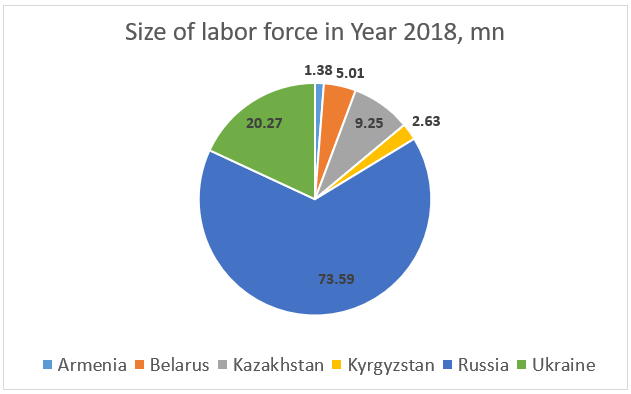

Russia’s own labor force declined by 3 percent in 1992-2018, totaling 73.6 million last year, according to the World Bank,2 and is bound to keep shrinking by 800,000-900,000 a year until 2025, according to researchers at the Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration (RANEPA). Putin’s plan aims to change this trajectory, attracting workers from Ukraine, which as of 2018 had nearly 20.3 million individuals aged 15 and older “who supply labor,” which is how the World Bank defines the labor force.

The Kremlin’s hope is that Ukraine and other CIS countries can continue to mitigate the decline of Russia’s own labor force until major social and health reforms aimed at re-stimulating births and extending longevity produce results in the longer term (if they ever do).

If Putin’s plan succeeds, it may also help to stop Russia’s depopulation, which resumed last year for the first time since 2009, with declining inbound migration failing to compensate for the difference between deaths and births. It was the number of migrants from Ukraine that dropped at the greatest rate in 2018, according to the RANEPA researchers. The net number of migrants from Ukraine declined by a whopping 393 percent from 48,800 in 2017 to 9,900 in 2018.

|

Net inbound migration, in thousands |

Year 2017 |

Year 2018 |

% change |

|

International migration, including |

156.2 |

89.9 |

-74% |

|

All CIS Countries |

152.4 |

93.8 |

-62% |

|

Azerbaijan |

9.6 |

11.8 |

19% |

|

Armenia |

5.7 |

5.4 |

-6% |

|

Belarus |

7.7 |

6 |

-28% |

|

Kazakhstan |

22.2 |

18.2 |

-22% |

|

Kyrgyzstan |

12.6 |

9.1 |

-38% |

|

Moldova |

6.6 |

5.3 |

-25% |

|

Tajikistan |

23.5 |

22.3 |

-5% |

|

Turkmenistan |

1.3 |

1.7 |

24% |

|

Uzbekistan |

14.6 |

4.1 |

-256% |

|

Ukraine |

48.8 |

9.9 |

-393% |

|

"Far abroad" countries |

3.8 |

-3.9 |

-197% |

The decline in the overall number of inbound migrants is believed to have been primarily driven by the fact that the ruble has lost much of its value against the dollar and other currencies, as well as by the considerable slowdown in Russia’s economy, making the country’s labor market less attractive.

Moreover, unlike the situation prior to the 2014 revolution in Ukraine, Russia now faces much stiffer competition for Ukrainian workers with the EU. Before Viktor Yanukovych was ousted, Russian strategists had hoped they could woo his government to bring Ukraine into the Moscow-led Eurasian Economic Union. Such an addition would have boosted the union’s labor force by 22 percent. Instead, post-Yanukovych Ukraine proceeded to sign association and trade agreements with the EU, eventually making it easier for Ukrainians to travel to and work in the EU. As a result, Ukrainian nationals received more first-time residence permits in the EU in 2017 than nationals of any other country (662,000), according to Eurostat, nearly 90 percent for work; of the total, 88 percent went to live in Poland. There may now be as many as 2 million or more Ukrainian migrants living in Poland alone, with at least hundreds of thousands more residing in other EU countries, compared to about 3 million in Russia.

Ukrainians who are legally employed in the EU and able to make the bloc’s average net minimum wage of 732 euros a month may find Putin’s offer of fast-track citizenship unenticing, given that the average Russian wage as of this year was under 590 euros (42,413 rubles). However, there are also many Ukrainian nationals working in the EU illegally—including, possibly, half of the Ukrainians working in Poland, according to a Ukrainian trade union leader’s 2018 estimate. Some of these illegal workers may perhaps find Putin’s invitation more attractive, and the same can be said of millions of Ukrainians still working in Ukraine, where the average monthly wage is about 340 euros.

While Putin’s hopes of integrating Ukraine into the Eurasian Economic Union were dashed by the 2014 revolution, the Russian leadership has refused to yield in its battle with the EU over Ukraine’s shrinking labor force and Putin’s April 24 decree is the latest evidence of that determination.

|

|

Eurasian Economic Union |

Eurasian Economic Union with Ukraine |

% difference |

|

Labor force, 2018, in millions |

91.9 |

112.1 |

22% |

|

GDP, constant dollars, 2017, in billions |

1958.7 |

2086 |

6% |

1Percentages refer to the working-age population with an advanced level of education who are in the labor force. Advanced education includes short-cycle tertiary education, a bachelor’s degree or equivalent education level, a master’s degree or equivalent education level or a doctoral degree or equivalent education level according to the International Standard Classification of Education.

2“Labor force” comprises people aged 15 and older who supply labor, according to the World Bank.