In the Thick of It

A blog on the U.S.-Russia relationship

This Week in History: The Rocket Launch That Didn’t Start a Nuclear War With Russia

Twenty-five years ago this week, a U.S.-Norwegian team of scientists launched a rocket with equipment to study the northern lights from the coast of Norway. Due to the rocket’s size, speed and trajectory—as well as some possible lapses in communication—Russian systems mistook it for a missile attack and went on high alert. One former CIA official called the Jan. 25, 1995, incident “the single most dangerous moment of the nuclear missile age.” But was it?

Indeed, Russia’s early-warning system was activated “up to the top, including [then President Boris] Yeltsin's ‘nuclear briefcase,’” according to one former Russian diplomat. However, based on multiple sources (including the ex-diplomat), officials in Moscow quickly realized the mistake and stood down. Moreover, according to Pavel Podvig, a leading expert on Russia’s strategic forces, there is even some evidence suggesting that the alarm didn’t reach Yeltsin’s emergency satchel on the day of the launch but, rather, the briefcase sequence was staged for him the next day. In fact, the Kremlin may have deliberately publicized how the alert about the launch went all the way up the chain of command in Russia’s early warning system (SPRN) to remind the West that Russia was still a nuclear powerhouse whose interests and opinions should be factored into decision-making on the world stage. Russia’s domestic power struggles also may have played a role: Playing up the threat allowed the country’s then Space Forces and Air Defense Force to prove their “usefulness” and to temporarily delay a bid by the Strategic Missile Forces to wrest away control of SPRN components (which eventually did occur in 1997-1999, though that re-subordination did not last).

Given all of what Russians calls podoplyoka (background), it should come as no surprise that renowned experts on Russia’s nuclear forces, such as Podvig, believe the danger of the incident has been seriously exaggerated. Some U.S. accounts of the incident also note that the Russians saw “within minutes” that the rocket posed no threat. Others, however, were far more alarmist, with one U.S. expert writing as recently as 2013 that “we came much closer to Armageddon after the Cold War ended than many realize. In January 1995, a global nuclear war almost started by mistake.”

The Russian-Western strategic relationship has seen its fair share of close calls that genuinely brought the world to the brink of a nuclear war. You can decide whether the Norwegian rocket incident belongs in this category by familiarizing yourself with a selection of Western and Russian accounts of the 1995 incident below.

Western Accounts

David Hoffman, “Cold-War Doctrines Refuse to Die,” The Washington Post, 03.15.1998:

- “For several tense minutes … confusion reigned… These may have been some of the most dangerous moments of the nuclear age.”

- “It triggered a heightened level of alert throughout the Russian strategic forces.”

- “It caused an alert to go off on each of the three nuclear ‘footballs.’”

- “Russian officials brush aside questions about the incident, saying it has been overblown in the West. Vladimir Dvorkin, [then the] director of the [Russian Defense Ministry’s] 4th Central Research Institute said he saw no danger from the Norwegian alert, ‘none at all.’”

Peter Vincent Pry, “War Scare: Russia and America on the Nuclear Brink,” 1999:

- “The single most dangerous moment of the nuclear missile age. Never before had a leader of any nuclear power opened his equivalent of the Russian ‘nuclear briefcase’ in earnest, in a situation where a real threat was perceived, and where an immediate decision to launch Armageddon was possible.”

Benjamin C. Garrett and John Hart, “Historical Dictionary of Nuclear, Biological and Chemical Warfare,” 2007:

- “Although the rocket carried no nuclear warhead, its trajectory caused Russia to mistake it for a submarine-launched nuclear missile. … Russia placed its nuclear forces on high alert.”

- “The Cheget, a briefcase linked to the nuclear weapons command and control system, was activated.”

- “Within minutes, however Russian observers verified that the rocket was heading away from Russian airspace and, thus, posed no threat.”

- “Afterward, it was established that the scientists had notified more than 30 countries, including Russia, of the planned launch but that this notice was not passed along to Russian radar operators. This incident remains the sole time that a nuclear briefcase is known to have been activated by any nuclear weapon state.”

Joseph Cirincione, “Nuclear Nightmares: Securing the World Before It Is Too Late,” 2013:

- “We came much closer to Armageddon after the Cold War ended than many realize. In January 1995, a global nuclear war almost started by mistake.”

- “Boris Yeltsin became the first Russian president to ever have the ‘nuclear suitcase’ open in front of him. He had just a few minutes to decide if he should push the button that would launch a barrage of nuclear missiles.”

- “We believe his senior military officials advised him that he had to launch. Thankfully, he concluded that his radars were in error.”

Seth D. Baum, “Confronting the Threat of Nuclear Winter,” Futures, 2015:

- “In 1995, Russian radar detected a scientific weather rocket launched off the northern coast of Norway. The Russians initially believed that it was a nuclear weapon launch. … Fortunately, Yeltsin and his associates correctly concluded that it was a false alarm.”

- “That this event … occurred after the Cold War during a time of relative calm between Russia and the U.S. speaks to the ongoing risk that exists.”

Seth D. Baum, “Risk-Risk Tradeoff Analysis of Nuclear Explosives for Asteroid Deflection,” Risk Analysis, November 2019:

- “No nuclear war has occurred since the advent of nuclear deterrence, but there may have been several near misses. … In 1995, after the Cold War, Russian radar operators mistakenly believed that a Norwegian-U.S. scientific weather rocket launch was a nuclear attack, allegedly prompting Russian President Yeltsin to contemplate launching in retaliation.”

Russian Accounts

Then President Boris Yeltsin, Financial Times, 01.27.1995:

- “I indeed yesterday used for the first time my ‘black’ suitcase with the button, which is always carried with me. I linked up instantly with the minister of defense, with all those military leader-generals whom I need, and we tracked the path of this rocket from beginning to end.”

Veronika Kutsilo, Kommersant, 01.27.1995:

- “The war in Chechnya undermined Russia’s image of a military superpower… Moscow had no choice but to try to launch a propaganda counter-offensive and the launch of the Norwegian rocket came in quite handy. Thanks to that rocket, Boris Yeltsin … reminded the whole world about his half-forgotten ‘nuclear briefcase.’”

- “Yeltsin could have intentionally referred to the briefcase to bring the West, which has been speaking about the weakness of the Russian armed forces, to its senses.”

Viktor Litovkin, Izvestia, 08.07.1997:

- Officers at the early-warning-system station “were quick to sort it out: The rocket posed no danger whatsoever to Russia.”

- Officer: “Its trajectory aimed toward Spitsbergen and therefore the situation required no extraordinary actions on our part.”

- “Well-informed sources” say at the time there was a proposal to subordinate missile defense to the commander of Strategic Missile Forces. This incident provided an opportunity to show Yeltsin how important missile defense men were and delay reform.

Nikolai Sokov1, “Could Norway Trigger a Nuclear War? Notes on the Russian Command and Control System,” PONARS-Eurasia, October 1997 [in English]:

- “The computer systems classified it as a combat missile and flashed a warning. The system was automatically activated up to the top, including Yeltsin's ‘nuclear briefcase.’ Then, in a matter of minutes, the situation was assessed and the alert status decreased back to normal. Reportedly, the alert did not even reach launch teams at missile bases.”

Sergei Ischenko, Trud, 01.11.2000:

- “The Norwegian rocket was barely in the air when the alarm went off in the Kremlin. The incident was sorted out quickly, however, and there were no military consequences.”

- “Those who were supposed to know about this launch didn’t learn about it in time. It is good that mankind was already forgetting about the psychosis of the Cold War at that time. Everyone had enough sense and time to sort the situation out.”

Pavel Podvig, “De-Alerting Reconsidered,” Russian Strategic Nuclear Forces blog, 01.24.2005:

- “With time, the story generated its own mythology… And … there is evidence that the danger of that particular incident has been seriously exaggerated.”

Anna Potekhina, “The ‘Observatory’ in Pechora,” Krasnaya zvezda, 03.27.2014:

- “But there were moments in the [Pechora, Russia-based Daryal] radar station’s history when the personnel were subjected to exceptional tasks, when the honor of not just the missile warning system, but of the government as a whole was at stake.”

- “The [Norwegian] rocket’s flight trajectory was similar to that of the American submarine-launched Trident ... missile, which could have been used for a high-altitude nuclear explosion. This would have temporarily disabled Russian radar warning of a missile attack, a strategy that was viewed as one potential way that the Americans could begin a massive nuclear attack.”

- “The launch of the Norwegian rocket put the world at risk of an exchange of nuclear strikes between Russia and the United States. On the next day, President Boris Yeltsin announced that he had used his ‘nuclear briefcase’ for the first time to contact his military advisers in an emergency and to discuss the situation. Later, it became known that Norway gave Russia an official warning on time. But something didn’t work.”

- “None of the officers were encouraged, but the political reputation of the new Russia was confirmed and trust in the Armed Forces was restored. And that, at the time, was the most important thing.”

Oleg Falichev, “Anti-Missile Umbrella for Russia,” Voenno-promyshlennyy kur’er, 10.09.2014:

- “Its trajectory was similar to that of the American submarine-launched Trident ... missile, which could have been used for a high-altitude nuclear explosion. This would have temporarily disabled Russian radar warning of a missile attack, a strategy that is viewed as one potential way to begin a massive nuclear attack.”

- “The launch of the Norwegian rocket put the world at risk of an exchange of nuclear strikes between Russia and the United States.”

Mikhail Rodkin, “Model of Nuclear Night: Options for the End of the World,” Nezavisimaya Gazeta, 12.25.2018:

- “The launch location [of the Norwegian research rocket] was indicated, but not the time—this depended on weather conditions. Apparently, this information did not reach the [Russian] military.”

- “At the time, the military was researching the possibility of a launch of a single high-altitude missile intended to cause strong electromagnetic interference, blinding radar systems and making them insensitive to an ensuing ballistic missile launch.”

- Offered the option of nuclear retaliation, “the president of Russia did not hurry, and the military soon reported that the missile was not approaching Russian territory and as such could not blind tracking systems.”

Timur Alimov, “On the Brink: 25 Years Ago Norway Almost Caused a Nuclear War,” Rossiyskaya Gazeta, 01.26.2020:

- “Although those present at the time of the event say that the crisis lasted around a half hour, it became the most serious crisis in the history of atomic weapons.”

Pavel Podvig, Interview with Russia Matters, 01.29.2020:

- “My understanding of how the Russian/Soviet system works tells me that it is highly unlikely that the alarm generated by that missile went anywhere up enough to reach Yeltsin, although it probably got to the level of the command center of the early-warning army. People I talked to at the time (and some time after) who had actual knowledge of the way the system works were very confident that it was not a serious incident.”

- “[T]he Russian system is not designed to launch anything in response to a single missile launch. More than that, the standard procedure is to wait for actual nuclear detonations on Russian territory. I just see no way how this incident could have resulted in a launch.”

- “I find the theory of a ‘nuclear suitcase’ scene staged for Yeltsin the next day quite plausible. So, no I don't believe it was anywhere close to the ‘single most dangerous incident.’ If I were to rank these cases … I would probably give it 3 out of 10. There were far more serious incidents during the Cold War.”

Footnotes:

1. Nikolai Sokov worked at the Soviet Union's and later Russia's Ministry of Foreign Affairs from 1987-1992, but later relocated to the U.S. and became a U.S. citizen.

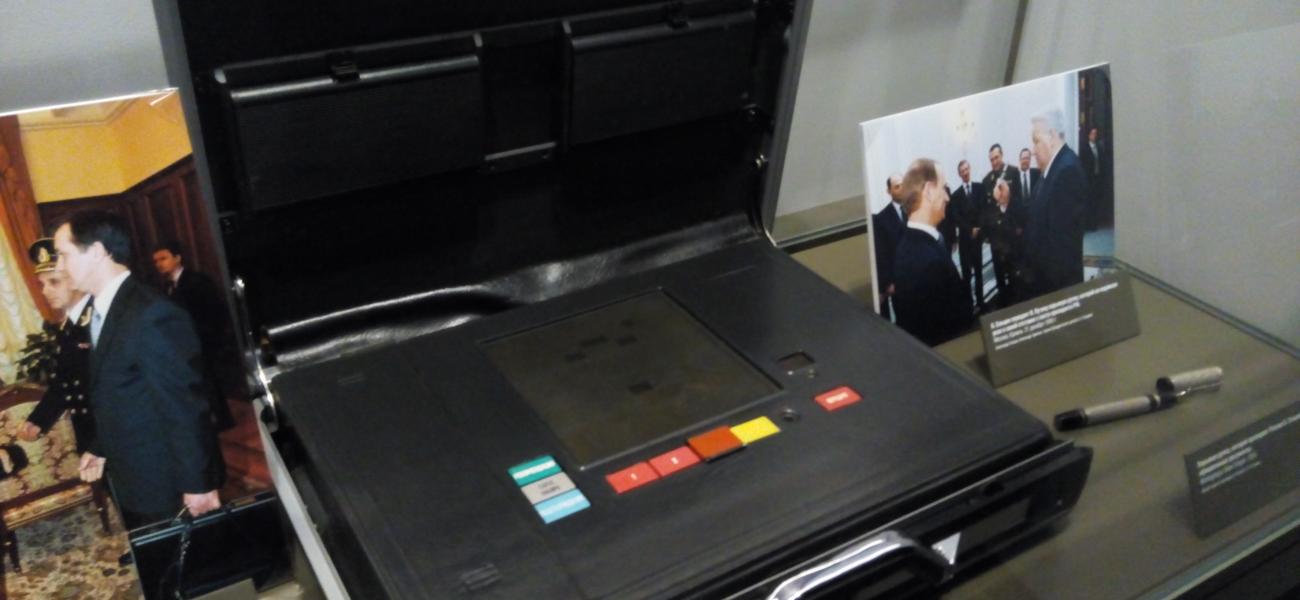

Photo: Yeltsin's nuclear briefcase on display at the Yeltsin Center in Yekaterinburg, Russia, November 2015. By Luba Suslyakova of AskUral.com.