As China Rises, Russia Tries to Make the Best of a Tough Situation

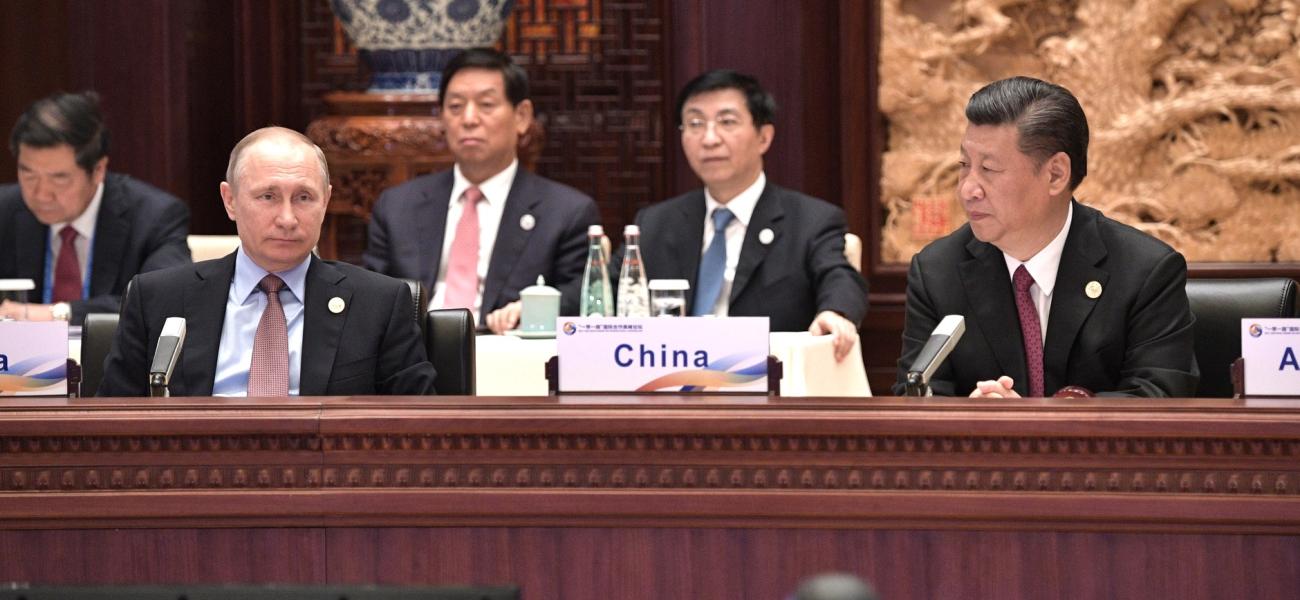

As China welcomed nearly 30 world leaders to Beijing this month to showcase its ambitious infrastructure project known as One Belt, One Road, or OBOR, Russian President Vladimir Putin was an honored guest. At the podium, he spoke positively of the planned trillion-dollar network of shipping routes, ports and related facilities, saying it sent “much needed signals” of stability amid political uncertainties riling the global economy. But Putin’s measured praise largely reflects Russia’s need to make the best of a bad situation: With its economy stymied by sanctions and low oil prices, and its relations with the West tense at best, Moscow has been deepening ties with China in recent years. Nonetheless, Russia understands all too well that China’s “project of the century,” if successful, and its rise on the global stage more generally are reshaping international power dynamics in a way that only highlights the profound economic disparity between the two states. The Sino-Russian relationship is increasingly asymmetrical and Russia is the weaker partner. What’s less clear is how that relationship might be affected by the most powerful Western nation to see OBOR as a threat and China as an adversary—namely, the United States.

A Bumpy Road (and Belt)

While Moscow has warmed to OBOR in the past two years, considerable unease still exists among Russian political elites about the project, also known as the “belt and road” initiative or the New Silk Road initiative, and attempts at genuine cooperation have been halting—again, in large part due to China’s relative economic might. The Kremlin made no formal acknowledgement of OBOR when it was proposed in 2013, and initially declined the Chinese invitation to join the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the project’s chief underwriter. Chinese President Xi Jinping’s decision to announce OBOR during a state visit to Kazakhstan, and his identification of Central Asia as a priority area for investment, was a signal to many members of the Russian political class that China was seeking to encroach upon an area of Russia’s “privileged interest.” The project was also viewed as compromising the viability of the Eurasian Economic Union, the Kremlin’s own integration scheme in the post-Soviet space.

As financial and political pressures on Russia mounted after the Ukraine crisis, however, the Kremlin came to see it had no realistic option other than to embrace OBOR. (Some Russian experts have attributed this to the persuasive arguments of First Deputy Prime Minister Igor Shuvalov, who convinced Putin that accommodation was in Russia’s best interest.) The Kremlin reversed its initial decision on participation in the AIIB, and Russia and China announced their intention to coordinate the planning processes of the EEU and OBOR.

To date, however, attempts to integrate the two remain rudimentary. The largest Chinese investment in Russia using OBOR funds has been the purchase of a 9.9% stake in the Yamal liquefied natural gas project in the Arctic, plus $12 billion in loans for it from two Chinese banks, which stepped in after the project’s Russian partners came under Western sanctions. Meanwhile, negotiations between Russia and China over the construction of a high-speed rail line between Moscow and Kazan are mired in disputes. Under an early agreement, that line was meant to extend through Siberia to Beijing, but then the Chinese decided to route it through Kazakhstan instead, reportedly slashing travel time by two-thirds. In short, Russian hopes for generous Chinese financing of infrastructure projects have been tempered by the realization that Chinese investors are oriented less toward friendship than profit.

Big Neighbor, Big Competitor

Russia’s disadvantages in competing with China in the post-Soviet space have also been evident in the unfolding of the New Silk Road initiative. Chinese total trade turnover tends to exceed that of Russia in the formerly Soviet Central Asian states, whose leaders—three of them present in Beijing—have emerged as enthusiastic supporters of OBOR. In contrast to Russia, Kazakhstan has actively formulated a comprehensive infrastructure plan and is the region’s largest recipient of Chinese funding. Even Belarus has markedly increased its trade turnover with China, including Chinese financing of the Great Stone Industrial Park near Minsk, which aims to locate Chinese manufacturers in close proximity to European markets. OBOR has also deflected Chinese attention away from the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, a less-than-robust grouping of China, Russia and four of the five states in formerly Soviet Central Asia. The Kremlin, well aware of its inability to compete economically with China, has recast the narrative about Central Asia, posing a division of labor in which the Kremlin provides security guarantees, while China provides capital. But this framing doesn’t alter the reality of an increasing Chinese presence in the region, which simultaneously indicates the lessening of Russian influence.

Relations Warmer, But Caveats Aplenty

There is no doubt that the Russian-Chinese relationship has grown substantially closer in the past few years. This is seen not only in rhetoric and symbolic actions—such as the deference paid to Putin at the OBOR forum—but also in the willingness of the Kremlin to allow China greater access to investment opportunities in Russia, notably in the energy sector and land-lease plans in the Russian Far East, and the easing of constraints in the sale of high-technology weaponry. The Russian-Chinese relationship has also been strengthened by the personal affinity between Putin and Xi, and their overall agreement on major international political issues, especially with respect to the hegemonic role played by the United States. Nonetheless, as Carnegie analyst Alexander Gabuev has noted, the much vaunted Russian pivot to China is largely a response to Western sanctions in the wake of the crises in Crimea and eastern Ukraine. Though Russia and China have become increasingly interdependent, Russia needs China more than China needs Russia.

Washington Also No Fan of OBOR

Here it’s worth noting that the United States, like Russia, has also viewed OBOR as a potential threat, but Washington’s position of power has allowed it to take a different tack than Moscow. While the latter modified its initial reaction to OBOR as a pragmatic concession, the United States has instead largely refrained from direct engagement. Security analyst Gal Luft notes that U.S. and Chinese officials detailed more than 100 areas of potential cooperation at the 2015 and 2016 meetings of the U.S.-China Strategic and Economic Dialogue without once mentioning OBOR. Washington adopted a more pro-active tactic with regard to Chinese plans to establish the AIIB, seeking to dissuade other states from membership in the bank. This effort largely ended in failure, as even America’s closest allies (except Japan) chose to jump on the Chinese bandwagon and joined the bank. Moreover, President Barack Obama’s pivot to Asia was rooted in the promotion of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which deliberately excluded China. For all its internationalist rhetoric, the Obama administration was surprisingly candid in explaining the importance of the TPP, reiterating in multiple formats: “We can’t let countries like China write the rules of the global economy.”

Although the Trump administration’s Asia policy is still evolving, the new U.S. president’s anti-China stance has paradoxically boosted China’s chances for greater clout on the international stage. First, Trump has remained true to his campaign promise to abandon the TPP, thus providing China with an unparalleled opportunity to expand its role in Asia, largely through OBOR. As a replacement for the TPP, China is promoting the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a free-trade agreement that includes the 10 member states of ASEAN and six major partners. Second, Trump’s ambivalence toward free trade and his critique of the negative consequences of globalization also offer China the opportunity to become the leading champion of globalization internationally. In the fall of 2016 and most notably in his January 2017 speech at the Davos Forum, Xi emerged as a fervent and outspoken defender of free trade and the market economy—whatever the ironies of that position for the leader of an ostensibly Communist state. (Europeans have been quite quiet: Western leaders, for the most part, stayed away from Beijing’s OBOR forum; and according to one recent report, the EU’s bureaucratic, rule-bound lack of flexibility keeps it from playing a bigger part in Eurasian integration projects.)

Belts and Roads Leading to a New World Order?

OBOR nicely symbolizes the structural changes underway in the distribution of power in the international order, with China becoming ever less hesitant to claim the mantle of global economic leadership, Russia trying to find its place vis-à-vis this powerful player and the U.S., for now, leaving the world guessing about its role in the “triangle.” Under Xi, China has abandoned the maxim, attributed to Deng Xiaoping, of “keeping a low profile while biding one’s time.” Xi signalled a change in China’s ambitions in a 2013 meeting with Obama when he heralded a “new type of great-power relations” between the two states. His speech at Davos and the OBOR forum represent further claims to China’s leadership role in the world economy, especially in the face of U.S. inaction. Russia under Putin, meanwhile, has demonstrated a remarkable ability to play a weak hand to its best advantage, but in dealing with China this has often meant rhetoric over substance. Putin’s task is to negotiate a role for Russian in the emerging new global order in which economic capabilities are seen to substitute in many respects for traditional projections of power measured according to military might. Putin also is confronted with China as a contiguous neighbour—a situation that is particularly discomforting in the Russian Far East—whose regional ambitions overlap with those of Russia in the post-Soviet space. Despite China’s relentless emphasis on cooperation, which rests on the premise of mutually beneficial outcomes, the reality is that China’s rise poses a challenge to the position of both Russia and the United States in the global system. How Russia is dealing with this we have seen; what Washington will do is an open question.

Jeanne L. Wilson

Jeanne Wilson teaches at Wheaton College where she is the Shelby Cullom Davis Professor of Russian studies, a professor of political science and coordinator of the school's international relations major. She is the author of "Strategic Partners: Russian-Chinese Relations in the Post-Soviet Era."

Photo from the official Kremlin website.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.